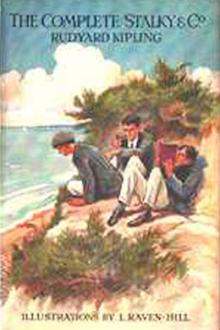

Stalky & Co., Rudyard Kipling [good beach reads .TXT] 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co., Rudyard Kipling [good beach reads .TXT] 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

They had heard that phrase till they were wearied. The “honor of the house” was Prout’s weak point, and they knew well how to flick him on the raw.

“If you order us to go down, sir, of course we’ll go,” said Stalky, with maddening politeness. But Prout knew better than that. He had tried the experiment once at a big match, when the three, self-isolated, stood to attention for half an hour in full view of all the visitors, to whom fags, subsidized for that end, pointed them out as victims of Prout’s tyranny. And Prout was a sensitive man.

In the infinitely petty confederacies of the Common-room, King and Macrea, fellow housemasters, had borne it in upon him that by games, and games alone, was salvation wrought. Boys neglected were boys lost. They must be disciplined. Left to himself, Prout would have made a sympathetic housemaster; but he was never so left, and with the devilish insight of youth, the boys knew to whom they were indebted for his zeal.

“Must we go down, sir?’ said McTurk.

“I don’t want to order you to do what a right-thinking boy should do gladly. I’m sorry.” And he lurched out with some hazy impression that he had sown good seed on poor ground.

“Now what does he suppose is the use of that?” said Beetle.

“Oh, he’s cracked. King jaws him in Common-room about not keepin’ us up to the mark, an’ Macrea burbles about ‘dithcipline,’ an’ old Heffy sits between ‘em sweatin’ big drops. I heard Oke (the Common-room butler) talking to Richards (Prout’s house-servant) about it down in the basement the other day when I went down to bag some bread,” said Stalky.

“What did Oke say?” demanded McTurk, throwing “Eric” into a corner.

“Oh, he said, ‘They make more nise nor a nest full o’ jackdaws, an’ half of it like we’d no ears to our heads that waited on ‘em. They talks over old Prout—what he’ve done an’ left undone about his boys. An’ how their boys be fine boys, an’ his’n be dom bad.’ Well, Oke talked like that, you know, and Richards got awf’ly wrathy. He has a down on King for something or other. Wonder why?”

“Why, King talks about Prout in form-room—makes allusions, an’ all that—only half the chaps are such asses they can’t see what he’s drivin’ at. And d’you remember what he said about the ‘Casual House’ last Tuesday? He meant us. They say he says perfectly beastly things to his own house, making fun of Prout’s,” said Beetle.

“Well, we didn’t come here to mix up in their rows,” McTurk said wrathfully. “Who’ll bathe after callover? King’s takin’ it in the cricket-field. Come on.” Turkey seized his straw and led the way.

They reached the sun-blistered pavilion over against the gray Pebbleridge just before roll-call, and, asking no questions, gathered from King’s voice and manner that his house was on the road to victory.

“Ah, ha!” said he, turning to show the light of his countenance. “Here we have the ornaments of the Casual House at last. You consider cricket beneath you, I believe “—the crowd, flannelled, sniggered “and from what I have seen this afternoon, I fancy many others of your house hold the same view. And may I ask what you purpose to do with your noble selves till tea-time?”

“Going down to bathe, sir,” said Stalky.

“And whence this sudden zeal for cleanliness? There is nothing about you that particularly suggests it. Indeed, so far as I remember—I may be at fault—but a short time ago—”

“Five years, sir,” said Beetle hotly.

King scowled. “One of you was that thing called a water-funk. Yes, a water-funk. So now you wish to wash? It is well. Cleanliness never injured a boy or—a house. We will proceed to business,” and he addressed himself to the callover board.

“What the deuce did you say anything to him for, Beetle?” said McTurk angrily, as they strolled towards the big, open sea-baths.

“‘Twasn’t fair—remindin’ one of bein’ a water-funk. My first term, too. Heaps of chaps are—when they can’t swim.”

“Yes, you ass; but he saw he’d fetched you. You ought never to answer King.”

“But it wasn’t fair, Stalky.”

“My Hat! You’ve been here six years, and you expect fairness. Well, you are a dithering idiot.”

A knot of King’s boys, also bound for the baths, hailed them, beseeching them to wash—for the honor of their house.

“That’s what comes of King’s jawin’ and messin’. Those young animals wouldn’t have thought of it unless he’d put it into their heads. Now they’ll be funny about it for weeks,” said Stalky. “Don’t take any notice.”

The boys came nearer, shouting an opprobrious word. At last they moved to windward, ostentatiously holding their noses.

“That’s pretty,” said Beetle. “They’ll be sayin’ our house stinks next.”

When they returned from the baths, damp-headed, languid, at peace with the world, Beetle’s forecast came only too true. They were met in the corridor by a fag—a common, Lower-Second fag—who at arm’s length handed them a carefully wrapped piece of soap “with the compliments of King’s House.”

“Hold on,” said Stalky, checking immediate attack. “Who put you up to this, Nixon? Rattray and White? (Those were two leaders in King’s house.) Thank you. There’s no answer.”

“Oh, it’s too sickening to have this kind o’ rot shoved on to a chap. What’s the sense of it? What’s the fun of it?” said McTurk.

“It will go on to the end of the term, though,” Beetle wagged his head sorrowfully. He had worn many jests threadbare on his own account.

In a few days it became an established legend of the school that Prout’s house did not wash and were therefore noisome. Mr. King was pleased to smile succulently in form when one of his boys drew aside from Beetle with certain gestures.

“There seems to be some disability attaching to you, my Beetle, or else why should Burton major withdraw, so to speak, the hem of his garments? I confess I am still in the dark. Will some one be good enough to enlighten me?”

Naturally, he was enlightened by half the form.

“Extraordinary! Most extraordinary! However, each house has its traditions, with which I would not for the world interfere. We have a prejudice in favor of washing. Go on, Beetle—from ‘jugurthatamen_’—and, if you can, avoid the more flagrant forms of guessing.”

Prout’s house was furious because Macrea’s and Hartopp’s houses joined King’s to insult them. They called a house-meeting after dinner—an excited and angry meeting of all save the prefects, whose dignity, though they sympathized, did not allow them to attend. They read ungrammatical resolutions, and made speeches beginning, “Gentlemen, we have met on this occasion,” and ending with, “It’s a beastly shame,” precisely as houses have done since time and schools began.

Number Five study attended, with its usual air of bland patronage. At last McTurk, of the lanthorn jaws, delivered himself:

“You jabber and jaw and burble, and that’s about all you can do. What’s the good of it? King’s house’ll only gloat because they’ve drawn you, and King will gloat, too. Besides, that resolution of Orrin’s is chock-full of bad grammar, and King’ll gloat over that.”

“I thought you an’ Beetle would put it right, an’—an’ we’d post it in the corridor,” said the composer meekly.

“Parsi_je_le_connai_. I’m not goin’ to meddle with the biznai,” said Beetle. “It’s a gloat for King’s house. Turkey’s quite right.”

“Well, won’t Stalky, then?”

But Stalky puffed out his cheeks and squinted down his nose in the style of Panurge, and all he said was, “Oh, you abject burblers!”

“You’re three beastly scabs!” was the instant retort of the democracy, and they went out amid execrations.

“This is piffling,” said McTurk. “Let’s get our sallies, and go and shoot bunnies.”

Three saloon-pistols, with a supply of bulleted breech-caps, were stored in Stalky’s trunk, and this trunk was in their dormitory, and their dormitory was a three-bed attic one, opening out of a ten-bed establishment, which, in turn, communicated with the great range of dormitories that ran practically from one end of the College to the other. Macrea’s house lay next to Prout’s, King’s next to Macrea’s, and Hartopp’s beyond that again. Carefully locked doors divided house from house, but each house, in its internal arrangements—the College had originally been a terrace of twelve large houses—was a replica of the next; one straight roof covering all.

They found Stalky’s bed drawn out from the wall to the left of the dormer window, and the latter end of Richards protruding from a two-foot-square cupboard in the wall.

“What’s all this? I’ve never noticed it before. What are you tryin’ to do, Fatty?”

“Fillin’ basins, Muster Corkran.” Richards’s voice was hollow and muffled. “They’ve been savin’ me trouble. Yiss.”

“‘Looks like it,” said McTurk. “Hi! You’ll stick if you don’t take care.”

Richards backed puffing.

“I can’t rache un. Yiss, ‘tess a turncock, Muster McTurk. They’ve took an’ runned all the watter-pipes a storey higher in the houses—runned ‘em all along under the ‘ang of the heaves, like. Runned ‘em in last holidays. I can’t rache the turncock.”

“Let me try,” said Stalky, diving into the aperture.

“Slip ‘ee to the left, then, Muster Corkran. Slip ‘ee to the left, an’ feel in the dark.”

To the left Stalky wriggled, and saw a long line of lead pipe disappearing up a triangular tunnel, whose roof was the rafters and boarding of the college roof, whose floor was sharp-edged joists, and whose side was the rough studding of the lath and plaster wall under the dormer.

“Rummy show. How far does it go?”

“Right along, Muster Corkran—right along from end to end. Her runs under the ‘ang of the heaves. Have ‘ee rached the stopcock yet? Mr. King got un put in to save us carryin’ watter from down-stairs to fill the basins. No place for a lusty man like old Richards. I’m tu thickabout to go ferritin’. Thank ‘ee, Muster Corkran.”

The water squirted through the tap just inside the cupboard, and, having filled the basins, the grateful Richards waddled away.

The boys sat round-eyed on their beds considering the possibilities of this trove. Two floors below them they could hear the hum of the angry house; for nothing is so still as a dormitory in mid-afternoon of a midsummer term.

“It has been papered over till now.” McTurk examined the little door. “If we’d only known before!”

“I vote we go down and explore. No one will come up this time o’ day. We needn’t keep cave’.”

They crawled in, Stalky leading, drew the door behind them, and on all fours embarked on a dark and dirty road full of plaster, odd shavings, and all the raffle that builders leave in the waste room of a house. The passage was perhaps three feet wide, and, except for the struggling light round the edges of the cupboards (there was one to each dormer), almost pitchy dark.

“Here’s Macrea’s house,” said Stalky, his eye at the crack of the third cupboard. “I can see Barnes’s name on his trunk. Don’t make such a row, Beetle! We can get right to the end of the Coll. Come on!… We’re in King’s house now—I can see a bit of Rattray’s trunk. How these beastly boards hurt one’s knees!” They heard his nails scraping, on plaster.

“That’s the ceiling below. Look out! If we smashed that the plaster ‘ud fall down in the lower dormitory,” said Beetle.

“Let’s,” whispered McTurk.

“An’ be collared first thing? Not much. Why, I can shove my hand ever so far up between these boards.”

Stalky thrust an arm to the elbow between the joists.

“No good stayin’ here. I vote we go back and talk it over. It’s

Comments (0)