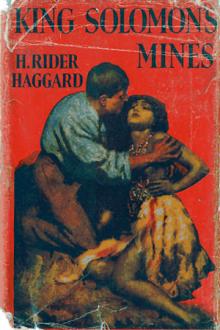

King Solomon's Mines, H. Rider Haggard [read me like a book TXT] 📗

- Author: H. Rider Haggard

- Performer: 0192834851

Book online «King Solomon's Mines, H. Rider Haggard [read me like a book TXT] 📗». Author H. Rider Haggard

Once we rose and tried to remonstrate, but were sternly repressed by Twala.

“Let the law take its course, white men. These dogs are magicians and evil-doers; it is well that they should die,” was the only answer vouchsafed to us.

About half-past ten there was a pause. The witch-finders gathered themselves together, apparently exhausted with their bloody work, and we thought that the performance was done with. But it was not so, for presently, to our surprise, the ancient woman, Gagool, rose from her crouching position, and supporting herself with a stick, staggered off into the open space. It was an extraordinary sight to see this frightful vulture-headed old creature, bent nearly double with extreme age, gather strength by degrees, until at last she rushed about almost as actively as her ill-omened pupils. To and fro she ran, chanting to herself, till suddenly she made a dash at a tall man standing in front of one of the regiments, and touched him. As she did this a sort of groan went up from the regiment which evidently he commanded. But two of its officers seized him all the same, and brought him up for execution. We learned afterwards that he was a man of great wealth and importance, being indeed a cousin of the king.

He was slain, and Twala counted one hundred and three. Then Gagool again sprang to and fro, gradually drawing nearer and nearer to ourselves.

“Hang me if I don’t believe she is going to try her games on us,” ejaculated Good in horror.

“Nonsense!” said Sir Henry.

As for myself, when I saw that old fiend dancing nearer and nearer, my heart positively sank into my boots. I glanced behind us at the long rows of corpses, and shivered.

Nearer and nearer waltzed Gagool, looking for all the world like an animated crooked stick or comma, her horrid eyes gleaming and glowing with a most unholy lustre.

Nearer she came, and yet nearer, every creature in that vast assemblage watching her movements with intense anxiety. At last she stood still and pointed.

“Which is it to be?” asked Sir Henry to himself.

In a moment all doubts were at rest, for the old hag had rushed in and touched Umbopa, alias Ignosi, on the shoulder.

“I smell him out,” she shrieked. “Kill him, kill him, he is full of evil; kill him, the stranger, before blood flows from him. Slay him, O king.”

There was a pause, of which I instantly took advantage.

“O king,” I called out, rising from my seat, “this man is the servant of thy guests, he is their dog; whosoever sheds the blood of our dog sheds our blood. By the sacred law of hospitality I claim protection for him.”

“Gagool, mother of the witch-finders, has smelt him out; he must die, white men,” was the sullen answer.

“Nay, he shall not die,” I replied; “he who tries to touch him shall die indeed.”

“Seize him!” roared Twala to the executioners; who stood round red to the eyes with the blood of their victims.

They advanced towards us, and then hesitated. As for Ignosi, he clutched his spear, and raised it as though determined to sell his life dearly.

“Stand back, ye dogs!” I shouted, “if ye would see tomorrow’s light. Touch one hair of his head and your king dies,” and I covered Twala with my revolver. Sir Henry and Good also drew their pistols, Sir Henry pointing his at the leading executioner, who was advancing to carry out the sentence, and Good taking a deliberate aim at Gagool.

Twala winced perceptibly as my barrel came in a line with his broad chest.

“Well,” I said, “what is it to be, Twala?”

Then he spoke.

“Put away your magic tubes,” he said; “ye have adjured me in the name of hospitality, and for that reason, but not from fear of what ye can do, I spare him. Go in peace.”

“It is well,” I answered unconcernedly; “we are weary of slaughter, and would sleep. Is the dance ended?”

“It is ended,” Twala answered sulkily. “Let these dead dogs,” pointing to the long rows of corpses, “be flung out to the hy�nas and the vultures,” and he lifted his spear.

Instantly the regiments began to defile through the kraal gateway in perfect silence, a fatigue party only remaining behind to drag away the corpses of those who had been sacrificed.

Then we rose also, and making our salaam to his majesty, which he hardly deigned to acknowledge, we departed to our huts.

“Well,” said Sir Henry, as we sat down, having first lit a lamp of the sort used by the Kukuanas, of which the wick is made from the fibre of a species of palm leaf, and the oil from clarified hippopotamus fat, “well, I feel uncommonly inclined to be sick.”

“If I had any doubts about helping Umbopa to rebel against that infernal blackguard,” put in Good, “they are gone now. It was as much as I could do to sit still while that slaughter was going on. I tried to keep my eyes shut, but they would open just at the wrong time. I wonder where Infadoos is. Umbopa, my friend, you ought to be grateful to us; your skin came near to having an air-hole made in it.”

“I am grateful, Bougwan,” was Umbopa’s answer, when I had translated, “and I shall not forget. As for Infadoos, he will be here by-and-by. We must wait.”

So we lit out pipes and waited.

For a long while—two hours, I should think—we sat there in silence, being too much overwhelmed by the recollection of the horrors we had seen to talk. At last, just as we were thinking of turning in—for the night drew nigh to dawn—we heard a sound of steps. Then came the challenge of a sentry posted at the kraal gate, which apparently was answered, though not in an audible tone, for the steps still advanced; and in another second Infadoos had entered the hut, followed by some half-dozen stately-looking chiefs.

“My lords,” he said, “I have come according to my word. My lords and Ignosi, rightful king of the Kukuanas, I have brought with me these men,” pointing to the row of chiefs, “who are great men among us, having each one of them the command of three thousand soldiers, that live but to do their bidding, under the king’s. I have told them of what I have seen, and what my ears have heard. Now let them also behold the sacred snake around thee, and hear thy story, Ignosi, that they may say whether or no they will make cause with thee against Twala the king.”

By way of answer Ignosi again stripped off his girdle, and exhibited the snake tattooed about him. Each chief in turn drew near and examined the sign by the dim light of the lamp, and without saying a word passed on to the other side.

Then Ignosi resumed his moocha, and addressing them, repeated the history he had detailed in the morning.

“Now ye have heard, chiefs,” said Infadoos, when he had done, “what say ye: will ye stand by this man and help him to his father’s throne, or will ye not? The land cries out against Twala, and the blood of the people flows like the waters in spring. Ye have seen to-night. Two other chiefs there were with whom I had it in my mind to speak, and where are they now? The hy�nas howl over their corpses. Soon shall ye be as they are if ye strike not. Choose then, my brothers.”

The eldest of the six men, a short, thick-set warrior, with white hair, stepped forward a pace and answered—

“Thy words are true, Infadoos; the land cries out. My own brother is among those who died to-night; but this is a great matter, and the thing is hard to believe. How know we that if we lift our spears it may not be for a thief and a liar? It is a great matter, I say, of which none can see the end. For of this be sure, blood will flow in rivers before the deed is done; many will still cleave to the king, for men worship the sun that still shines bright in the heavens, rather than that which has not risen. These white men from the Stars, their magic is great, and Ignosi is under the cover of their wing. If he be indeed the rightful king, let them give us a sign, and let the people have a sign, that all may see. So shall men cleave to us, knowing of a truth that the white man’s magic is with them.”

“Ye have the sign of the snake,” I answered.

“My lord, it is not enough. The snake may have been placed there since the man’s childhood. Show us a sign, and it will suffice. But we will not move without a sign.”

The others gave a decided assent, and I turned in perplexity to Sir Henry and Good, and explained the situation.

“I think that I have it,” said Good exultingly; “ask them to give us a moment to think.”

I did so, and the chiefs withdrew. So soon as they had gone Good went to the little box where he kept his medicines, unlocked it, and took out a note-book, in the fly-leaves of which was an almanack. “Now look here, you fellows, isn’t tomorrow the 4th of June?” he said.

We had kept a careful note of the days, so were able to answer that it was.

“Very good; then here we have it—‘4 June, total eclipse of the moon commences at 8.15 Greenwich time, visible in Teneriffe—/South Africa/, &c.’ There’s a sign for you. Tell them we will darken the moon tomorrow night.”

The idea was a splendid one; indeed, the only weak spot about it was a fear lest Good’s almanack might be incorrect. If we made a false prophecy on such a subject, our prestige would be gone for ever, and so would Ignosi’s chance of the throne of the Kukuanas.

“Suppose that the almanack is wrong,” suggested Sir Henry to Good, who was busily employed in working out something on a blank page of the book.

“I see no reason to suppose anything of the sort,” was his answer. “Eclipses always come up to time; at least that is my experience of them, and it especially states that this one will be visible in South Africa. I have worked out the reckonings as well as I can, without knowing our exact position; and I make out that the eclipse should begin here about ten o’clock tomorrow night, and last till half-past twelve. For an hour and a half or so there should be almost total darkness.”

“Well,” said Sir Henry, “I suppose we had better risk it.”

I acquiesced, though doubtfully, for eclipses are queer cattle to deal with—it might be a cloudy night, for instance, or our dates might be wrong—and sent Umbopa to summon the chiefs back. Presently they came, and I addressed them thus—

“Great men of the Kukuanas, and thou, Infadoos, listen. We love not to show our powers, for to do so is to interfere with the course of nature, and to plunge the world into fear and confusion. But since this matter is a great one, and as we are angered against the king because of the slaughter we have seen, and because of the act of the Isanusi Gagool, who would have put our friend Ignosi to death, we have determined to break

Comments (0)