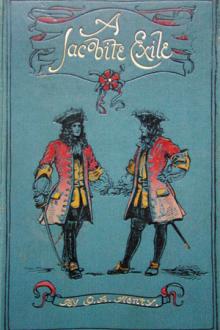

A Jacobite Exile, G. A. Henty [interesting books to read for teens .txt] 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

- Performer: -

Book online «A Jacobite Exile, G. A. Henty [interesting books to read for teens .txt] 📗». Author G. A. Henty

"Well, Master Englishman," Ben Soloman said, as he came up to his bedside, "what do you think of things?"

"I do not know what to think," Charlie said feebly. "I do not know where I am, or why I am here. I remember that there was a fray in the street, and I suppose I was hurt. But why was I brought here, instead of being taken to my lodgings?"

"Because you would be no use to me in your lodging, and you may be a great deal of use to me here," Ben Soloman said. "You know you endeavoured to entrap me into a plot against the king's life."

Charlie shook his head, and looked wonderingly at the speaker.

"No, no," he said, "there was no plot against the king's life. I only asked if you would use your influence among your friends to turn popular feeling against Augustus."

"Nothing of the kind," the Jew said harshly. "You wanted him removed by poison or the knife. There is no mistake about that, and that is what I am going to swear, and what, if you want to save your life, you will have to swear too; and you will have to give the names of all concerned in the plot, and to swear that they were all agreed to bring about the death of the king. Now you understand why you were brought here. You are miles away from another house, and you may shout and scream as loud as you like. You are in my power."

"I would die rather than make a false accusation."

"Listen to me," the Jew said sternly. "You are weak now, too weak to suffer much. This day week I will return, and then you had best change your mind, and sign a document I shall bring with me, with the full particulars of the plot to murder the king, and the names of those concerned in it. This you will sign. I shall take it to the proper authorities, and obtain a promise that your life shall be spared, on condition of your giving evidence against these persons."

"I would never sign such a villainous document," Charlie said.

"You will sign it," Ben Soloman said calmly. "When you find yourself roasting over a slow charcoal fire, you will be ready to sign anything I wish you to."

So saying, he turned and left the room. He talked for some time to the men outside, then Charlie heard him ride off.

"You villain," he said to himself. "When you come, at the end of a week, you will not find me here; but, if I get a chance of having a reckoning with you, it will be bad for you."

Charlie's progress was apparently slow. The next day he was able to sit up and feed himself. Two days later he could totter across the room, and lie down before the fire. The men were completely deceived by his acting, and, considering any attempt to escape, in his present weak state, altogether impossible, paid but little heed to him, the peasant frequently absenting himself for hours together.

Looking from his window, Charlie saw that the hut was situated in a thick wood, and, from the blackened appearance of the peasant's face and garments, he guessed him to be a charcoal burner, and therefore judged that the trees he saw must form part of a forest of considerable extent.

The weather was warm, and his other guard often sat, for a while, outside the door. During his absence, Charlie lifted the logs of wood piled beside the hearth, and was able to test his returning strength, assuring himself that, although not yet fully recovered, he was gaining ground daily. He resolved not to wait until the seventh day; for Ben Soloman might change his mind, and return before the day he had named. He determined, therefore, that on the sixth day he would make the attempt.

He had no fear of being unable to overcome his Jewish guard, as he would have the advantage of a surprise. He only delayed as long as possible, because he doubted his powers of walking any great distance, and of evading the charcoal burner, who would, on his return, certainly set out in pursuit of him. Moreover, he wished to remain in the hut nearly up to the time of the Jew's return, as he was determined to wait in the forest, and revenge himself for the suffering he had caused him, and for the torture to which he intended to put him.

The evening before the day on which he decided to make the attempt, the charcoal burner and the Jew were in earnest conversation. The word signifying brigand was frequently repeated, and, although he could not understand much more than this, he concluded, from the peasant's talk and gestures, that he had either come across some of these men in the forest, or had gathered from signs he had observed, perhaps from their fires, that they were there.

The Jew shrugged his shoulders when the narration was finished. The presence of brigands was a matter of indifference to him. The next day, the charcoal burner went off at noon.

"Where does he go to?" Charlie asked his guard.

"He has got some charcoal fires alight, and is obliged to go and see to them. They have to be kept covered up with wet leaves and earth, so that the wood shall only smoulder," the man said, as he lounged out of the hut to his usual seat.

Charlie waited a short time, then went to the pile of logs, and picked out a straight stick about a yard long and two inches in diameter. With one of the heavier ones he could have killed the man, but the fellow was only acting under the orders of his employer, and, although he would doubtless, at Ben Soloman's commands, have roasted him alive without compunction, he had not behaved with any unkindness, and had, indeed, seemed to do his best for him.

Taking the stick, he went to the door. He trod lightly, but in the stillness of the forest the man heard him, and glanced round as he came out.

Seeing the stick in his hand he leaped up, exclaiming, "You young fool!" and sprang towards him.

He had scarce time to feel surprise, as Charlie quickly raised the club. It described a swift sweep, fell full on his head, and he dropped to the ground as if shot.

Charlie ran in again, seized a coil of rope, bound his hands and feet securely, and dragged him into the hut. Then he dashed some cold water on his face. The man opened his eyes, and tried to move.

"You are too tightly bound to move, Pauloff," he said. "I could have killed you if I had chosen, but I did not wish to. You have not been unkind to me, and I owe you no grudge; but tell your rascally employer that I will be even with him, someday, for the evil he has done me."

"You might as well have killed me," the man said, "for he will do so when he finds I let you escape."

"Then my advice to you is, be beforehand with him. You are as strong a man as he is, and if I were in your place, and a man who meant to kill me came into a lonely hut like this, I would take precious good care that he had no chance of carrying out his intentions."

Charlie then took two loaves of black bread and a portion of goat's flesh from the cupboard; found a bottle about a quarter full of coarse spirits, filled it up with water and put it in his pocket, and then, after taking possession of the long knife his captive wore in his belt, went out of the hut and closed the door behind him.

He had purposely moved slowly about the hut, as he made these preparations, in order that the Jew should believe that he was still weak; but, indeed, the effort of dragging the man into the hut had severely taxed his strength, and he found that he was much weaker than he had supposed.

The hut stood in a very small clearing, and Charlie had no difficulty in seeing the track by which the cart had come, for the marks of the wheels were still visible in the soft soil. He followed this until, after about two miles' walking, he came to the edge of the wood. Then he retraced his steps for a quarter of a mile, turned off, and with some difficulty made his way into a patch of thick undergrowth, where, after first cutting a formidable cudgel, he lay down, completely exhausted.

Late in the afternoon he was aroused from a doze by the sound of footsteps, and, looking through the screen of leaves, he saw his late jailers hurrying along the path. The charcoal burner carried a heavy axe, while the Jew, whose head was bound up with a cloth, had a long knife in his girdle. They went as far as the end of the forest, and then retraced their steps slowly. They were talking loudly, and Charlie could gather, from the few words he understood, and by their gestures, something of the purport of their conversation.

"I told you it was of no use your coming on as far as this," the Jew said. "Why, he was hardly strong enough to walk."

"He managed to knock you down, and afterwards to drag you into the house," the other said.

"It does not require much strength to knock a man down with a heavy club, when he is not expecting it, Conrad. He certainly did drag me in, but he was obliged to sit down afterwards, and I watched him out of one eye as he was making his preparations, and he could only just totter about. I would wager you anything he cannot have gone two hundred yards from the house. That is where we must search for him. I warrant we shall find him hidden in a thicket thereabouts."

"We shall have to take a lantern then, for it will be dark before we get back."

"Our best plan will be to leave it alone till morning. If we sit outside the hut, and take it in turns to watch, we shall hear him when he moves, which he is sure to do when it gets dark. It will be a still night, and we should hear a stick break half a mile away. We shall catch him, safe enough, before he has gone far."

"Well, I hope we shall have him back before Ben Soloman comes," the charcoal burner said, "or it will be worse for both of us. You know as well as I do he has got my neck in a noose, and he has got his thumb on you."

"If we can't find this Swede, I would not wait here for any money. I would fly at once."

"You would need to fly, in truth, to get beyond Ben Soloman's clutches," the charcoal burner said gruffly. "He has got agents all over the country."

"Then what would you do?"

"There is only one thing to do. It is our lives or his. When he rides up tomorrow, we will meet him at the door as if nothing had happened, and, with my axe, I will cleave his head asunder as he comes in. If he sees me in time to retreat, you shall stab him in the back. Then we will dig a big hole in the wood, and throw him in, and we will kill his horse and bury it with him.

"Who would ever be the wiser? I was

Comments (0)