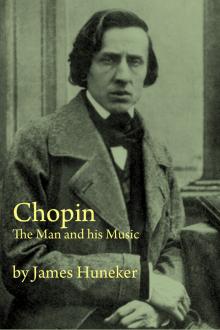

Chopin: The Man and His Music, James Huneker [free e books to read online txt] 📗

- Author: James Huneker

- Performer: -

Book online «Chopin: The Man and His Music, James Huneker [free e books to read online txt] 📗». Author James Huneker

Oh! what is this that knows the road I came, The flame turned cloud, the cloud returned to flame, The lifted, shifted steeps and all the way?

That draws around me at last this wind-warm space, And in regenerate rapture turns my face Upon the devious coverts of dismay?

During the last half of the nineteenth century two men became rulers of musical emotion, Richard Wagner and Frederic Francois Chopin. The music of the latter is the most ravishing gesture that art has yet made.

Wagner and Chopin, the macrocosm and the microcosm! “Wagner has made the largest impersonal synthesis attainable of the personal influences that thrill our lives,” cries Havelock Ellis. Chopin, a young man slight of frame, furiously playing out upon the keyboard his soul, the soul of his nation, the soul of his time, is the most individual composer that has ever set humming the looms of our dreams. Wagner and Chopin have a motor element in their music that is fiercer, intenser and more fugacious than that of all other composers. For them is not the Buddhistic void, in which shapes slowly form and fade; their psychical tempo is devouring. They voiced their age, they moulded their age and we listen eagerly to them, to these vibrile prophetic voices, so sweetly corrosive, bardic and appealing. Chopin being nearer the soil in the selection of forms, his style and structure are more naive, more original than Wagner’s, while his medium, less artificial, is easier filled than the vast empty frame of the theatre. Through their intensity of conception and of life, both men touch issues, though widely dissimilar in all else. Chopin had greater melodic and as great harmonic genius as Wagner; he made more themes, he was, as Rubinstein wrote, the last of the original composers, but his scope was not scenic, he preferred the stage of his soul to the windy spaces of the music-drama. His is the interior play, the eternal conflict between body and soul. He viewed music through his temperament and it often becomes so imponderable, so bodiless as to suggest a fourth dimension in the art. Space is obliterated. With Chopin one does not get, as from Beethoven, the sense of spiritual vastness, of the overarching sublime.

There is the pathos of spiritual distance, but it is pathos, not sublimity. “His soul was a star and dwelt apart,” though not in the Miltonic or Wordsworthian sense. A Shelley-like tenuity at times wings his thought, and he is the creator of a new thrill within the thrill.

The charm of the dying fall, the unspeakable cadence of regret for the love that is dead, is in his music; like John Keats he sometimes sees:—

Charm’d magic casements, opening on the foam Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

Chopin, “subtle-souled psychologist,” is more kin to Keats than Shelley, he is a greater artist than a thinker. His philosophy is of the beautiful, as was Keats’, and while he lingers by the river’s edge to catch the song of the reeds, his gaze is oftener fixed on the quiring planets. He is nature’s most exquisite sounding-board and vibrates to her with intensity, color and vivacity that have no parallel. Stained with melancholy, his joy is never that of the strong man rejoicing in his muscles. Yet his very tenderness is tonic and his cry is ever restrained by an Attic sense of proportion. Like Alfred De Vigny, he dwelt in a “tour d’ivoire” that faced the west and for him the sunrise was not, but O! the miraculous moons he discovered, the sunsets and cloud-shine! His notes cast great rich shadows, these chains of blown-roses drenched in the dew of beauty. Pompeian colors are too restricted and flat; he divulges a world of half-tones, some “enfolding sunny spots of greenery,” or singing in silvery shade the song of chromatic ecstasy, others “huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail” and black upon black. Chopin is the color genius of the piano, his eye was attuned to hues the most fragile and attenuated; he can weave harmonies that are as ghostly as a lunar rainbow. And lunar-like in their libration are some of his melodies—glimpses, mysterious and vast, as of a strange world.

His utterances are always dynamic, and he emerges betimes, as if from Goya’s tomb, and etches with sardonic finger Nada in dust. But this spirit of denial is not an abiding mood; Chopin throws a net of tone over souls wearied with rancors and revolts, bridges “salty, estranged seas” of misery and presently we are viewing a mirrored, a fabulous universe wherein Death is dead, and Love reigns Lord of all.

IIHeine said that “every epoch is a sphinx which plunges into the abyss as soon as its problem is solved.” Born in the very upheaval of the Romantic revolution—a revolution evoked by the intensity of its emotion, rather than by the power of its ideas—Chopin was not altogether one of the insurgents of art. Just when his individual soul germinated, who may tell? In his early music are discovered the roots and fibres of Hummel and Field. His growth, involuntary, inevitable, put forth strange sprouts, and he saw in the piano, an instrument of two dimensions, a third, and so his music deepened and took on stranger colors. The keyboard had never sung so before; he forged its formula. A new apocalyptic seal of melody and harmony was let fall upon it.

Sounding scrolls, delicious arabesques gorgeous in tint, martial, lyric, “a resonance of emerald,” a sobbing of fountains—as that Chopin of the Gutter, Paul Verlaine, has it—the tear crystallized midway, an arrested pearl, were overheard in his music, and Europe felt a new shudder of sheer delight.

The literary quality is absent and so is the ethical—Chopin may prophesy but he never flames into the divers tongues of the upper heaven. Compared with his passionate abandonment to the dance, Brahms is the Lao-tsze of music, the great infant born with gray hair and with the slow smile of childhood. Chopin seldom smiles, and while some of his music is young, he does not raise in the mind pictures of the fatuous romance of youth. His passion is mature, self-sustained and never at a loss for the mot propre. And with what marvellous vibration he gamuts the passions, festooning them with carnations and great white tube roses, but the dark dramatic motive is never lost in the decorative wiles of this magician. As the man grew he laid aside his pretty garlands and his line became sterner, its traceries more gothic; he made Bach his chief god and within the woven walls of his strange harmonies he sings the history of a soul, a soul convulsed by antique madness, by the memory of awful things, a soul lured by Beauty to secret glades wherein sacrificial rites are performed to the solemn sounds of unearthly music. Like Maurice de Guerin, Chopin perpetually strove to decipher Beauty’s enigma and passionately demanded of the sphinx that defies:

“Upon the shores of what oceans have they rolled the stone that hides them, O Macareus?”

His name was as the stroke of a bell to the Romancists; he remained aloof from them though in a sympathetic attitude. The classic is but the Romantic dead, said an acute critic. Chopin was a classic without knowing it; he compassed for the dances of his land what Bach did for the older forms. With Heine he led the spirit of revolt, but enclosed his note of agitation in a frame beautiful. The color, the “lithe perpetual escape” from the formal deceived his critics, Schumann among the rest. Chopin, like Flaubert, was the last of the idealists, the first of the realists. The newness of his form, his linear counterpoint, misled the critics, who accused him of the lack of it.

Schumann’s formal deficiency detracts from much of his music, and because of their formal genius Wagner and Chopin will live.

To Chopin might be addressed Sar Merodack Peladan’s words: “When your hand writes a perfect line the Cherubim descend to find pleasure therein as in a mirror.” Chopin wrote many perfect lines; he is, above all, the faultless lyrist, the Swinburne, the master of fiery, many rhythms, the chanter of songs before sunrise, of the burden of the flesh, the sting of desire and large-moulded lays of passionate freedom. His music is, to quote Thoreau, “a proud sweet satire on the meanness of our life.” He had no feeling for the epic, his genius was too concentrated, and though he could be furiously dramatic the sustained majesty of blank verse was denied him. With musical ideas he was ever gravid but their intensity is parent to their brevity. And it must not be forgotten that with Chopin the form was conditioned by the idea. He took up the dancing patterns of Poland because they suited his vivid inner life; he transformed them, idealized them, attaining to more prolonged phraseology and denser architecture in his Ballades and Scherzi—but these periods are passionate, never philosophical.

All artists are androgynous; in Chopin the feminine often prevails, but it must be noted that this quality is a distinguishing sign of masculine lyric genius, for when he unbends, coquets and makes graceful confessions or whimpers in lyric loveliness at fate, then his mother’s sex peeps out, a picture of the capricious, beautiful tyrannical Polish woman. When he stiffens his soul, when Russia gets into his nostrils, then the smoke and flame of his Polonaises, the tantalizing despair of his Mazurkas are testimony to the strong man-soul in rebellion. But it is often a psychical masquerade. The sag of melancholy is soon felt, and the old Chopin, the subjective Chopin, wails afresh in melodic moodiness.

That he could attempt far flights one may see in his B flat minor Sonata, in his Scherzi, in several of the Ballades, above all in the F

minor Fantasie. In this great work the technical invention keeps pace with the inspiration. It coheres, there is not a flaw in the reverberating marble, not a rift in the idea. If Chopin, diseased to death’s door, could erect such a Palace of Dreams, what might not he have dared had he been healthy? But forth from his misery came sweetness and strength, like honey from the lion. He grew amazingly the last ten years of his existence, grew with a promise that recalls Keats, Shelley, Mozart, Schubert and the rest of the early slaughtered angelic crew. His flame-like spirit waxed and waned in the gusty surprises of a disappointed life. To the earth for consolation he bent his ear and caught echoes of the cosmic comedy, the far-off laughter of the hills, the lament of the sea and the mutterings of its depths.

These things with tales of sombre clouds and shining skies and whisperings of strange creatures dancing timidly in pavonine twilights, he traced upon the ivory keys of his instrument and the world was richer for a poet. Chopin is not only the poet of the piano, he is also the poet of music, the most poetic of composers. Compared with him Bach seems a maker of solid polyphonic prose, Beethoven a scooper of stars, a master of growling storms, Mozart a weaver of gay tapestries, Schumann a divine stammerer. Schubert, alone of all the composers, resembles him in his lyric prodigality. Both were masters of melody, but Chopin was the master-workman of the two and polished, after bending and beating, his theme fresh from the fire of his forge. He knew that to complete his “wailing Iliads” the strong hand of the reviser was necessary, and he also realized that nothing is more difficult for the genius than to retain his gift. Of all natures the most prone to pessimism, procrastination and vanity,

Comments (0)