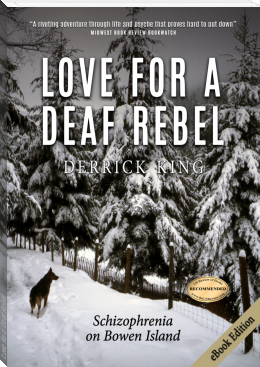

Love for a Deaf Rebel, Derrick King [funny books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Derrick King

- Performer: -

Book online «Love for a Deaf Rebel, Derrick King [funny books to read .txt] 📗». Author Derrick King

“Then unload them, and hide your ammunition.”

Snow fell upon snow. The weight of the snow pressed the boughs down like arches, turning the driveway into a tunnel of white. I put chains on the truck tires and parked it at the bottom of the driveway next to the road. For two weeks, Pearl and I commuted, on our separate shifts, by walking up and down the driveway in the snow, with groceries in our backpacks and flashlights in our hands or teeth.

“I’m going to the store,” Pearl announced one evening.

She dressed warmly and walked out into the night, down the driveway to the truck. An hour later, she returned with a carton of milk.

“We don’t need to buy cow milk. We have goat milk.”

“I wanted to rent a movie, but no players were left. I saw Arlette in the store, and we talked.”

“We also need to talk. Would you like a margarita?”

Pearl nodded. I mixed the drinks. “Cheers. I think we have three choices. One: we continue to live like we are living now. We share our house but live separate lives.”

Pearl shook her head.

“Two: we separate and divorce.”

“Do you want a divorce?”

“No. Three: You see a doctor. I can go with you if you want. You can’t live with suspicion about everyone. You will never be happy. You will never have a family.”

Pearl finished her drink in one shot. “I want children!”

“Then you must see a doctor.”

Pearl burst into tears. “I’ll kill myself.”

“No!” I tried to hug her, but she sat as if paralyzed.

“I have a counselor.”

“Sometimes, we should see her together. May I call her?”

Pearl nodded and gave me a card from her purse. The address was far from where she had asked me to drop her off.

At bedtime, I walked downstairs to stoke the stove and saw Pearl poking pages from a notepad into the fire. I retreated before she saw me.

In the morning, I called the old counselor on the card Pearl gave me. She would only say that Pearl was no longer her client. I thought Pearl had much to gain by my calling the new counselor at the Resource Centre for Abused Women whose name I had seen on the card in her bag, so I called her, too.

She was indignant I had called and became rude when I told her Pearl’s mental health was deteriorating and she needed care. When I said she didn’t need to take my word for it, but she did need to call Pearl’s mother and the RCMP, she hung up on me.

If I told people that my wife had tried many times to kill me, they would think I was mentally ill, and if they cared for me they would refer me to a doctor. But when Pearl told people that her husband had tried many times to kill her, they thought she was sane—and someone had referred her to a center for abused women. In the 1980s, there had been a backlash against abuse of women by men, so whenever a woman said she was being abused by a man, she was invariably believed—and if there was no physical abuse, then there must be psychological abuse. This was ideal for women who really were being abused and who needed emotional support and separation from their abusers, but it worked against Pearl, who was not abused but mentally unwell and needed diagnosis and treatment: because I was male, I was silenced, and Pearl’s delusions were reinforced.

Pearl was furious I had called her counselor. “I’m shocked! I said you could call my old counselor! My new counselor is private!”

“That means she can’t help you. You need a counselor who talks to your family.”

“How did you find out about my new counselor?”

“Your calls to her were on the telephone bill.”

“But I didn’t bring our telephone bill home.”

“I asked the telephone company for copies, to pay the bills.”

I asked Pearl for the bus schedule. I saw S. Sgt. Zaharia written on it in unfamiliar handwriting. “Who is this?”

Pearl looked embarrassed. “He is Laurent’s boss. Laurent refused to arrest you, so I complained to his boss.”

I telephoned Staff Sergeant Zaharia from my office.

“I’m glad you called. Your wife keeps coming to our counter making allegations about you, Laurent, the RCMP, and the West Vancouver Police. She’s been in here four times, each time more agitated. Can you call her off?”

“What allegations? That I’m trying to kill her?”

“That was the first time. Now she says you’re running drugs from Mexico by motorcycle, but we know you haven’t crossed the border in three years. Something is wrong with her. She needs help.”

“I don’t know how to help. She pushes back everything I try.”

“When we suggested she see a psychiatrist, she became hysterical and had to be escorted out the door by two constables. I see a pistol is registered to your address. I recommend Laurent store it, for your safety.”

I called Laurent. “I just spoke to Staff Sergeant Zaharia. He told me what Pearl’s been up to. Can you store my guns?”

“Sure. You’d be surprised how often I store guns for couples.”

“I’ll bring them tomorrow after Pearl gets on the 5:30 ferry.”

“I’ll have coffee. Don’t forget to wrap them; if you walk in here with a gun in your hand, I’ll have to shoot you.”

That night, Pearl elbowed me in bed because she wanted to talk. “Where are the bullets?”

I stared at her, dumbfounded.

“The gun has no bullets. Why did you remove them?”

“For our safety. How did you know?”

“I tried to shoot a tree, but nothing happened. Why did you remove my protection?”

“We have too many arguments now. We might fight.”

Pearl nodded weirdly. I was terrified. I waited until I heard her sleeping before I allowed myself to sleep.

I called Laurent from work the next morning.

“Where the hell were you? I waited an hour, so I was late going on patrol.”

“While I was talking to you yesterday, Pearl tried to test-fire the gun, but I’d already unloaded it. She’s probably more paranoid now. The tension at home is driving me nuts!”

“Derrick, I used to admire you, but I feel sorry for you now.”

I called Arlette. “I’m calling to ask for your help for Pearl. Can we talk?”

“What right do you have to call anyone about Pearl?” she hissed.

“She’s my wife. She needs to see a doctor, but I don’t know how to get her to one. Did she tell you about the RCMP? Can you help?”

“What we talk about is between us!” Arlette hung up on me.

The telephone rang. “Derrick, this is Franco, the drywaller. I heard you were selling your house.”

I felt like I was being gaslighted. “We’re not selling our house!”

“That’s not what I heard, but if you change your mind, call me.”

The atmosphere at home was explosive. When the telephone rang a few days later, I heard TTY tones and signed, “For you.” Pearl went to the visitors’ room and closed the door.

After Franco’s unnerving call, I wanted to know if Pearl was selling our house, so I put an office Dictaphone next to the kitchen telephone and recorded the tones.

When Pearl came out, she signed, “Please call my dentist to make an appointment for me. It is hard to make appointments through the MRC.”

Later, I played my recording into our TTY and could read every word. Her call was from a deafie in Los Angeles with whom she was planning to stay for a month.

Pearl was planning for life on her own.

At morning chore time, I left the footpath floodlights off to enjoy the moonlight bathing the snowy landscape. I stood at the top of the hill and looked down. The barn looked like a spaceship on a chalk planet, a life-support vessel under the stars. I walked down, turned on the lights, and squinted until my night vision left me. I did the chores, but Mouse ignored his feed.

I called Gus. “Mouse won’t eat. He’s standing in front of his manger and shifting back and forth.”

“Damn serious. I’ll be right there.”

“I’ll leave the barn lights on. We’ll be at work when you arrive.”

When I returned home, Gus’s Subaru station wagon was parked next to our truck at the bottom of the driveway.

Pearl was cooking. “Something is wrong. Gus’s car is here, so I didn’t do the chores. I waited for you.”

I put my overshoes back on, Pearl put on her farm clothes, and we walked to the barn. I was still in my suit and overcoat.

Gus and Donna were watching their daughter walk Mouse around a brown circle trodden into the snow. Cigarette butts lay everywhere. Country music on the barn radio added to the surrealism.

“How is Mouse?” I signed and said.

“We brought a vet from the mainland. It’s colic. What did you feed him?” said Gus.

“The same as always: alfalfa-timothy, Buckerfield’s horse mix, vitamins.”

“The vet put his arm up his ass,” said Donna. “He gave him an enema. He poured oil down his nose. He gave him drugs. No difference. Walking him is all we can do.”

“He’s hurtin’,” said Gus. “Appaloosas are tough, though. Maybe he’ll pull through.”

“Poor Mouse!” cried their daughter, massaging his belly.

At morning chore time, I found Donna walking Mouse. A thermos bottle stood atop a fencepost. “He keeps lying down and kicking. Next time he goes down, I don’t know if he’ll get up.”

When I arrived home from work, Gus was sitting in our kitchen, drunk. Pearl leaned against the counter, frustrated and furious, not knowing what to do with him.

“Dead!” Gus shouted, his voice slurred.

“I’m sorry.” I felt like an undertaker with a bereaved family member.

“Gone to the great Trout Lake in the sky. I need another drink.”

“Don’t give it to him,” Pearl signed. I didn’t interpret.

“I have only two beers left.” I opened them both, taking one for myself. “To Mouse,” I signed and said, holding up my can.

“He’s lying in your field. Tomorrow he’ll be frozen solid. I wanna bury him there. I’ll make a deal with Eddie for his backhoe.”

When I did the chores the next morning, I saw a gray mound dusted with snow in the corner of the field. Mouse rests under Trout Lake Farm today.

“I decided to move out. I work on Saturday, so I will leave on Sunday.”

I knew it was futile, but I signed, “Don’t go. Stay with Whisky and me.” I hugged her.

She stood stiffly and didn’t hug me. “I am sorry. It will be hard for you in winter. You must care for the animals and keep the fire burning every day. Please stay away when I move. Arlette will come at four o’clock to help me.”

“I will stay here while you are moving out because we must agree on what you take. Will you return?”

“I need to think. Everything changed after I discovered who you are. It is hard for me to explain my feelings to you.”

“Let’s see Dr. Foreman together. He helps couples. He signs, too.”

“You go. There is nothing wrong with me.”

“Will you stay at Arlette’s after you leave?”

“That is my secret. I am taking the truck. I need to be independent.”

“Is that why you wanted me to buy the jeep? Were you planning to leave four months ago?”

Pearl walked into the visitors’ room. I heard the tapping of keys, so I put the Dictaphone next to the kitchen telephone, lifted the handset, and tape-recorded the TTY tones. When I was alone, I played the recording into the TTY and learned that Pearl would move in with Arlette, but she would store her furniture with Arlette’s friend, Bruce.

On Saturday morning, the alarm clock rang at 5:25 a.m. I tapped Pearl on the shoulder to wake her up for work and changed the alarm time for me to wake up for the morning chores. As I rolled over, Pearl tapped me on the shoulder.

“Why do you look sleepy? What were you doing while I was asleep?”

Even though it was our last full day together, I worked on the house as I had done every Saturday for three years. Saturdays were important because the Building Centre didn’t open on Sundays in winter.

Pearl brought home a dozen empty cardboard cartons. She made dinner, and we ate in silence. While she packed her life into boxes, I followed her, both to

Comments (0)