Biology, Karl Irvin Baguio [the speed reading book txt] 📗

- Author: Karl Irvin Baguio

Book online «Biology, Karl Irvin Baguio [the speed reading book txt] 📗». Author Karl Irvin Baguio

Chapter 24: Blood and Circulation

Circulatory Systems

Single-celled organisms are in constant contact with their environments, obtaining nutrients and oxygen directly across the cell surface. The same holds true for small and simple plants and animals, such as algae, bryophytes, sponges, cnidarians, and flatworms. Larger and more complex plants and animals require methods for transporting materials to and from cells far removed from the external environment. These organisms have evolved transport systems.

Circulatory systems function to transport materials to and from cells throughout an organism. Organisms ranging from plants to animals have different nutritional requirements. Due to these differences, various species have evolved distinct circulatory processes to assist with their specific transport needs.

Plants

Transport systems are found in vascular plants. Vascular networks provide intercellular communication in terrestrial plants. The systems consist of tubelike connective tissues organized into xylem and phloem. Xylem transports water and minerals in the plants, while phloem transports food materials and hormones.

Xylem and phloem tissues are grouped in arrangements called vascular bundles. In monocot plants, the vascular bundles are scattered throughout the parenchyma tissue in no particular pattern. In dicot plants, the vascular bundles occur in a circle around a central region of pith. In woody dicot plants, new xylem forms on the inside of the cambium each season; the old xylem forms the annual rings of the plant.

Animals

In animals, the transport system is generally called a circulatory system because the blood flows through a circuit. Most animals have one or more organs called hearts for pumping blood. The channels through which the blood flows are the arteries (which lead away from the heart), the veins (which lead to the heart), and the capillaries (the microscopic blood vessels between arteries and veins).

In animals, such as earthworms, the circulatory system consists of blood, channels, and five pulsating vessels that function as hearts, rushing blood through the vessels to all the earthworm’s body parts. Gases bind to hemoglobin in the blood.

Terrestrial arthropods have an open circulatory system. A tubelike heart pumps blood into a dorsal blood vessel, which empties into the arthropod’s body cavity, or hemocoel. Contractions of the body muscles gradually move blood back toward the animal’s heart.

All vertebrates have a single, strong muscular heart to pump the blood. In fishes, the blood accumulates in a thin-walled receiving chamber called the atrium. The blood then passes through a valve into a pumping chamber, a ventricle. The ventricle contracts and forces blood out to the gills, where gas exchange occurs, and from there to the remainder of the body. Veins bring the blood back to the atrium.

Amphibians, such as frogs, have a three-chambered heart. The heart has a right and a left atrium and a single ventricle. In reptiles, a muscular septum exists between the two sides of the ventricle, creating a primitive four-chambered heart. Birds have a more sophisticated four-chambered heart than reptiles. One ventricle pumps blood to the lungs for gas exchange, while the second pumps oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body tissues. Mammals also have a four-chambered heart.

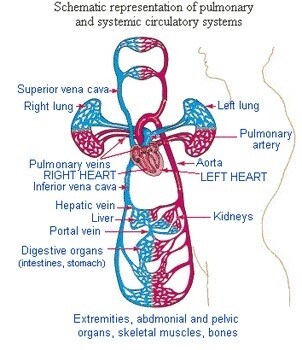

Human Circulatory System

The human circulatory system functions to transport blood and oxygen from the lungs to the various tissues of the body. The heart pumps the blood throughout the body. The lymphatic system is an extension of the human circulatory system that includes cell-mediated and antibody-mediated immune systems. The components of the human circulatory system include the heart, blood, red and white blood cells, platelets, and the lymphatic system.

Heart

The human heart is about the size of a clenched fist. It contains four chambers: two atria and two ventricles. Oxygen-poor blood enters the right atrium through a major vein called the vena cava. The blood passes through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. Next, the blood is pumped through the pulmonary artery to the lungs for gas exchange. Oxygen-rich blood returns to the left atrium via the pulmonary vein. The oxygen-rich blood flows through the bicuspid (mitral) valve into the left ventricle, from which it is pumped through a major artery, the aorta. Two valves called semilunar valves are found in the pulmonary artery and aorta.

The ventricles contract about 70 times per minute, which represents a person’s pulse rate. Blood pressure, in contrast, is the pressure exerted against the walls of the arteries. Blood pressure is measured by noting the height to which a column of mercury can be pushed by the blood pressing against the arterial walls. A normal blood pressure is a height of 120 millimeters of mercury during heart contraction (systole) and a height of 80 millimeters of mercury during heart relaxation (diastole). Normal blood pressure is usually expressed as “120 over 80.”

Coronary arteries supply the heart muscle with blood. The heart is controlled by nerves that originate on the right side in the upper region of the atrium at the sinoatrial node. This node is called the pacemaker. It generates nerve impulses that spread to the atrioventricular node, where the impulses are amplified and spread to other regions of the heart by nerves called Purkinje fibers.

Blood

Blood is the medium of transport in the body. The fluid portion of the blood, the plasma, is a straw-colored liquid composed primarily of water. All the important nutrients, the hormones, and the clotting proteins, as well as the waste products, are transported in the plasma. Red blood cells and white blood cells are also suspended in the plasma. Plasma from which the clotting proteins have been removed is called serum.

Red blood cells

Red blood cells are also called erythrocytes. These are disk-shaped cells produced in the bone marrow. Red blood cells have no nucleus, and their cytoplasm is filled with hemoglobin.

Hemoglobin is a red-pigmented protein that binds loosely to oxygen atoms and carbon dioxide molecules. It is the mechanism of transport of these substances. (Much carbon dioxide is also transported as bicarbonate ions.) Hemoglobin also binds to carbon monoxide. Unfortunately, this binding is irreversible, so it often leads to carbon monoxide poisoning.

A red blood cell circulates for about 120 days and is then destroyed in the spleen, an organ located near the stomach and composed primarily of lymph node tissue. When the red blood cell is destroyed, its iron component is preserved for reuse in the liver. The remainder of the hemoglobin converts to bilirubin. This amber substance is the chief pigment in human bile, which is produced in the liver.

Red blood cells commonly have immune-stimulating polysaccharides called antigens on the surface of their cells. Individuals having the A antigen have blood type A (as well as anti-B antibodies); individuals having the B antigen have blood type B (as well as anti-A antibodies); individuals having the A and B antigens have blood type AB (but no anti-A or anti-B antibodies); and individuals having no antigens have blood type O (as well as anti-A and anti-B antibodies).

White blood cells

White blood cells are referred to as leukocytes. They are generally larger than red blood cells and have clearly defined nuclei. They are also produced in the bone marrow and have various functions in the body. Certain white blood cells called lymphocytes are essential components of the immune system (discussed later in this chapter). Other cells called neutrophils and monocytes function primarily as phagocytes; that is, they attack and engulf invading microorganisms. About 30 percent of the white blood cells are lymphocytes, about 60 percent are neutrophils, and about 8 percent are monocytes. The remaining white blood cells are eosinophils and basophils. Their functions are uncertain; however, basophils are believed to function in allergic responses.

Platelets

Platelets are small disk-shaped blood fragments produced in the bone marrow. They lack nuclei and are much smaller than erythrocytes. Also known technically as thrombocytes, they serve as the starting material for blood clotting. The platelets adhere to damaged blood vessel walls, and thromboplastin is liberated from the injured tissue. Thromboplastin, in turn, activates other clotting factors in the blood. Along with calcium ions and other factors, thromboplastin converts the blood protein prothrombin into thrombin. Thrombin then catalyzes the conversion of its blood protein fibrinogen into a protein called fibrin, which forms a patchwork mesh at the injury site. As blood cells are trapped in the mesh, a blood clot forms.

Lymphatic system

The lymphatic system is an extension of the circulatory system consisting of a fluid known as lymph, capillaries called lymphatic vessels, and structures called lymph nodes. Lymph is a watery fluid derived from plasma that has seeped out of the blood system capillaries and mingled with the cells. Instead of returning to the heart through the blood veins, this lymph enters a series of one-way lymphatic vessels that return the fluid to the circulatory system. Along the way, the ducts pass through hundreds of tiny, capsulelike bodies called lymph nodes. Located in the neck, armpits, and groin, the lymph nodes contain cells that filter the lymph and phagocytize foreign particles.

The spleen is composed primarily of lymph node tissue. Lying close to the stomach, the spleen is also the site where red blood cells are destroyed. The spleen serves as a reserve blood supply for the body.

The lymph nodes are also the primary sites of the white blood cells called lymphocytes. The body has two kinds of lymphocytes: B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes. Both of these cells can be stimulated by microorganisms or other foreign materials in the blood. These antigens are picked up by phagocytes and lymph and delivered to the lymph nodes. Here, the lymphocytes are stimulated through a process called the immune response.

Certain antigens, primarily those of fungi and protozoa, stimulate the T-lymphocytes. After stimulation, these lymphocytes leave the lymph nodes, enter the circulation, and proceed to the site where the antigens of microorganisms were detected. The T-lymphocytes interact with the microorganisms cell to cell and destroy them. This process is called cell-mediated immunity.

B-lymphocytes are stimulated primarily by bacteria, viruses, and dissolved materials. On stimulation, the B-lymphocytes revert to large antibody-producing cells called plasma cells. The plasma cells synthesize proteins called antibodies, which are released into the circulation. The antibodies flow to the antigen site and destroy the microorganisms by chemically reacting with them in a highly specific manner. The reaction encourages phagocytosis, neutralizes many microbial toxins, eliminates the ability of microorganisms to move, and causes them to bind together in large masses. This process is called antibody-mediated immunity. After the microorganisms have been removed, the antibodies remain in the bloodstream and provide lifelong protection to the body. Thus, the body becomes immune to specific disease microorganisms.

Comments (0)