Biology, Karl Irvin Baguio [the speed reading book txt] 📗

- Author: Karl Irvin Baguio

Book online «Biology, Karl Irvin Baguio [the speed reading book txt] 📗». Author Karl Irvin Baguio

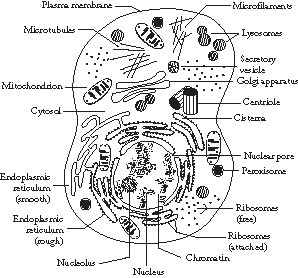

Within the cytoplasm of eukaryote cells are a number of membrane-bound bodies called organelles (“little organs”) that provide a specialized function within the cell.

One example of an organelle is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The ER is a series of membranes extending throughout the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. In some places, the ER is studded with submicroscopic bodies called ribosomes. This type of ER is called rough ER. In other places, there are no ribosomes. This type of ER is called smooth ER. The rough ER is the site of protein synthesis in a cell because it contains ribosomes; however, the smooth ER lacks ribosomes and is responsible for producing lipids. Within the ribosomes, amino acids are actually bound together to form proteins. Cisternae are spaces within the folds of the ER membranes.

Another organelle is the Golgi apparatus (also called Golgi body). The Golgi apparatus is a series of flattened sacs, usually curled at the edges. In the Golgi body, the cell’s proteins and lipids are processed and packaged before being sent to their final destination. To accomplish this function, the outermost sac of the Golgi body often bulges and breaks away to form droplike vesicles known as secretory vesicles.

An organelle called the lysosome (see Figure 3-1) is derived from the Golgi body. It is a droplike sac of enzymes in the cytoplasm. These enzymes are used for digestion within the cell. They break down particles of food taken into the cell and make the products available for use; they also help break down old cell organelles. Enzymes are also contained in a cytoplasmic body called the peroxisome.

Figure 3-1 The components of an idealized eukaryotic cell. The diagram shows the relative sizes and locations of the cell parts.

The organelle that releases quantities of energy to form adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the mitochondrion (the plural form is mitochondria). Because mitochondria are involved in energy release and storage, they are called the “powerhouses of the cells.”

Green plant cells, for example, contain organelles known as chloroplasts, which function in the process of photosynthesis. Within chloroplasts, energy from the sun is absorbed and transformed into the energy of carbohydrate molecules. Plant cells specialized for photosynthesis contain large numbers of chloroplasts, which are green because the chlorophyll pigments within the chloroplasts are green. Leaves of a plant contain numerous chloroplasts. Plant cells not specializing in photosynthesis (for example, root cells) are not green.

An organelle found in mature plant cells is a large, fluid-filled central vacuole. The vacuole may occupy more than 75 percent of the plant cell. In the vacuole, the plant stores nutrients, as well as toxic wastes. Pressure within the growing vacuole may cause the cell to swell.

The cytoskeleton is an interconnected system of fibers, threads, and interwoven molecules that give structure to the cell. The main components of the cytoskeleton are microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments. All are assembled from subunits of protein.

The centriole organelle is a cylinderlike structure that occurs in pairs. Centrioles function in cell division.

Many cells have specialized cytoskeletal structures called flagella and cilia. Flagella are long, hairlike organelles that extend from the cell, permitting it to move. In prokaryotic cells, such as bacteria, the flagella rotate like the propeller of a motorboat. In eukaryotic cells, such as certain protozoa and sperm cells, the flagella whip about and propel the cell. Cilia are shorter and more numerous than flagella. In moving cells, the cilia wave in unison and move the cell forward. Paramecium is a well-known ciliated protozoan. Cilia are also found on the surface of several types of cells, such as those that line the human respiratory tract.

Nucleus

Prokaryotic cells lack a nucleus; the word prokaryotic means “primitive nucleus.” Eukaryotic cells, on the other hand, have a distinct nucleus.

The nucleus of eukaryotic cells is composed primarily of protein and deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. The DNA is tightly wound around special proteins called histones; the mixture of DNA and histone proteins is called chromatin. The chromatin is folded even further into distinct threads called chromosomes. Functional segments of the chromosomes are referred to as genes. Approximately 21,000 genes are located in the nucleus of all human cells.

The nuclear envelope, an outer membrane, surrounds the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell. The nuclear envelope is a double membrane, consisting of two lipid layers (similar to the plasma membrane). Pores in the nuclear envelope allow the internal nuclear environment to communicate with the external nuclear environment.

Within the nucleus are two or more dense organelles referred to as nucleoli (the singular form is nucleolus). In nucleoli, submicroscopic particles known as ribosomes are assembled before their passage out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm.

Although prokaryotic cells have no nucleus, they do have DNA. The DNA exists freely in the cytoplasm as a closed loop. It has no protein to support it and no membrane covering it. A bacterium typically has a single looped chromosome.

Cell wall

Many kinds of prokaryotes and eukaryotes contain a structure outside the cell membrane called the cell wall. With only a few exceptions, all prokaryotes have thick, rigid cell walls that give them their shape. Among the eukaryotes, some protists, and all fungi and plants, have cell walls. Cell walls are not identical in these organisms, however. In fungi, the cell wall contains a polysaccharide called chitin. Plant cells, in contrast, have no chitin; their cell walls are composed exclusively of the polysaccharide cellulose.

Cell walls provide support and help cells resist mechanical pressures, but they are not solid, so materials are able to pass through rather easily. Cell walls are not selective devices, as plasma membranes are.

Chapter 4: Cells and Energy

The Laws of Thermodynamics

Life can exist only where molecules and cells remain organized. All cells need energy to maintain organization. Physicists define energy as the ability to do work; in this case, the work is the continuation of life itself.

Energy has been expressed in terms of reliable observations known as the laws of thermodynamics. There are two such laws. The first law of thermodynamics states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed. This law implies that the total amount of energy in a closed system (for example, the universe) remains constant. Energy neither enters nor leaves a closed system.

Within a closed system, energy can change, however. For instance, the chemical energy in gasoline is released when the fuel combines with oxygen and a spark ignites the mixture within a car’s engine. The gasoline’s chemical energy is changed into heat energy, sound energy, and the energy of motion.

The second law of thermodynamics states that the amount of available energy in a closed system is decreasing constantly. Energy becomes unavailable for use by living things because of entropy, which is the degree of disorder or randomness of a system. The entropy of any closed system is constantly increasing. In essence, any closed system tends toward disorganization.

Unfortunately, the transfers of energy in living systems are never completely efficient. Every body movement, every thought, and every chemical reaction in the cells involves a shift of energy and a measurable decrease of energy available to do work in the process. For this reason, considerably more energy must be taken into the system than is necessary to carry out the actions of life.

Chemical Reactions

Most chemical compounds do not combine with one another automatically, nor do chemical compounds break apart automatically. The great majority of the chemical reactions that occur within living things must be energized. This means that the atoms of a molecule must be separated by energy put into the system. The energy forces apart the atoms in the molecules and allows the reaction to take place.

To initiate a chemical reaction, a type of “spark,” referred to as the energy of activation, is needed. For example, hydrogen and oxygen can combine to form water at room temperature, but the reaction requires activation energy.

Any chemical reaction in which energy is released is called an exergonic reaction. In an exergonic chemical reaction, the products end up with less energy than the reactants. Other chemical reactions are endergonic reactions. In endergonic reactions, energy is obtained and trapped from the environment. The products of endergonic reactions have more energy than the reactants taking part in the chemical reaction. For example, plants carry out the process of photosynthesis, in which they trap energy from the sun to form carbohydrates (see Chapter 5).

The activation energy needed to spark an exergonic or endergonic reaction can be heat energy or chemical energy. Reactions that require activation energy can also proceed in the presence of biological catalysts. Catalysts are substances that speed up chemical reactions but remain unchanged themselves. Catalysts work by lowering the required amount of activation energy for the chemical reaction. For example, hydrogen and oxygen combine with one another in the presence of platinum. In this case, platinum is the catalyst. In biological systems, the most common catalysts are protein molecules called enzymes. Enzymes are absolutely essential if chemical reactions are to occur in cells.

Enzymes

The chemical reactions in all cells of living things operate in the presence of biological catalysts called enzymes. Because a particular enzyme catalyzes only one reaction, there are thousands of different enzymes in a cell catalyzing thousands of different chemical reactions. The substance changed or acted on by an enzyme is its substrate. The products of a chemical reaction catalyzed by an enzyme are end products.

All enzymes are composed of proteins. (Proteins are chains of amino acids; see Chapter 2.) When an enzyme functions, a key portion of the enzyme, called the active site, interacts with the substrate. The active site closely matches the molecular configuration of the substrate. After this interaction has taken place, a change in shape in the active site places a physical stress on the substrate. This physical stress aids the alteration of the substrate and produces the end products. During the time the active site is associated with the substrate, the combination is referred to as the enzyme-substrate complex. After the enzyme has performed its work, the product or products are released from the enzyme’s active site. The enzyme is then free to function in another chemical reaction.

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions occur extremely fast. They happen about a million times faster than uncatalyzed reactions. With some exceptions, the names of enzymes end in “–ase.” For example, the enzyme that breaks down hydrogen peroxide to water and hydrogen is catalase. Other enzymes include amylase, hydrolase, peptidase, and kinase.

The rate of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction depends on a number of factors, such as the concentration of the substrate, the acidity and temperature of the environment, and the presence of other chemicals. At higher temperatures, enzyme reactions occur more rapidly, but only up to a point. Because enzymes are proteins, excessive amounts of heat can change their structures, rendering them inactive. An enzyme altered by heat is said to be denatured.

Enzymes work together in metabolic pathways. A metabolic pathway is a sequence of chemical reactions occurring in a cell. A single enzyme-catalyzed reaction may be one of multiple reactions in a metabolic pathway. Metabolic pathways may be of two general types: catabolic and anabolic. Catabolic pathways involve the breakdown or digestion of large, complex molecules. The general term for this process is catabolism. Anabolic pathways involve the synthesis of large

Comments (0)