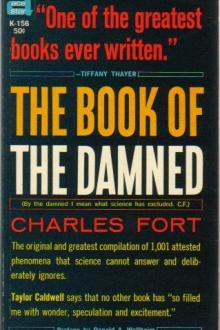

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

St. Augustine, with his orthodoxy, was never in—well, very much worse—difficulties than are the faithful here. By due disregard of a datum or so, our own acceptance that it was a steel object that had fallen from the sky to this earth, in Tertiary times, is not forced upon one. We offer ours as the only synthetic expression. For instance, in Science Gossip, 1887-58, it is described as a meteorite: in this account there is nothing alarming to the pious, because, though everything else is told, its geometric form is not mentioned.

It's a cube. There is a deep incision all around it. Of its faces, two that are opposite are rounded.

Though I accept that our own expression can only rather approximate to Truth, by the wideness of its inclusions, and because it seems, of four attempts, to represent the only complete synthesis, and can be nullified or greatly modified by data that we, too, have somewhere disregarded, the only means of nullification that I can think of would be demonstration that this object is a mass of iron pyrites, which sometimes forms geometrically. But the analysis mentions not a trace of sulphur. Of course our weakness, or impositiveness, lies in that, by anyone to whom it would be agreeable to find sulphur in this thing, sulphur would be found in it—by our own intermediatism there is some sulphur in everything, or sulphur is only a localization or emphasis of something that, unemphasized, is in all things.

So there have, or haven't, been found upon this earth things that fell from the sky, or that were left behind by extra-mundane visitors to this earth—

A yarn in the London Times, June 22, 1844: that some workmen, quarrying rock, close to the Tweed, about a quarter of a mile below Rutherford Mills, discovered a gold thread embedded in the stone at a depth of 8 feet: that a piece of the gold thread had been sent to the office of the Kelso Chronicle.

Pretty little thing; not at all frowsy; rather damnable.

London Times, Dec. 24, 1851:

That Hiram De Witt, of Springfield, Mass., returning from California, had brought with him a piece of auriferous quartz about the size of a man's fist. It was accidentally dropped—split open—nail in it. There was a cut-iron nail, size of a six-penny nail, slightly corroded. "It was entirely straight and had a perfect head."

Or—California—ages ago, when auriferous quartz was forming—super-carpenter, million of miles or so up in the air—drops a nail.

To one not an intermediatist, it would seem incredible that this datum, not only of the damned, but of the lowest of the damned, or of the journalistic caste of the accursed, could merge away with something else damned only by disregard, and backed by what is called "highest scientific authority"—

Communication by Sir David Brewster (Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1845-51):

That a nail had been found in a block of stone from Kingoodie Quarry, North Britain. The block in which the nail was found was nine inches thick, but as to what part of the quarry it had come from, there is no evidence—except that it could not have been from the surface. The quarry had been worked about twenty years. It consisted of alternate layers of hard stone and a substance called "till." The point of the nail, quite eaten with rust, projected into some "till," upon the surface of the block of stone. The rest of the nail lay upon the surface of the stone to within an inch of the head—that inch of it was embedded in the stone.

Although its caste is high, this is a thing profoundly of the damned—sort of a Brahmin as regarded by a Baptist. Its case was stated fairly; Brewster related all circumstances available to him—but there was no discussion at the meeting of the British Association: no explanation was offered—

Nevertheless the thing can be nullified—

But the nullification that we find is as much against orthodoxy in one respect as it is against our own expression that inclusion in quartz or sandstone indicates antiquity—or there would have to be a revision of prevailing dogmas upon quartz and sandstone and age indicated by them, if the opposing data should be accepted. Of course it may be contended by both the orthodox and us heretics that the opposition is only a yarn from a newspaper. By an odd combination, we find our two lost souls that have tried to emerge, chucked back to perdition by one blow:

Pop. Sci. News, 1884-41:

That, according to the Carson Appeal, there had been found in a mine, quartz crystals that could have had only 15 years in which to form: that, where a mill had been built, sandstone had been found, when the mill was torn down, that had hardened in 12 years: that in this sandstone was a piece of wood "with a nail in it."

Annals of Scientific Discovery, 1853-71:

That, at the meeting of the British Association, 1853, Sir David Brewster had announced that he had to bring before the meeting an object "of so incredible a nature that nothing short of the strongest evidence was necessary to render the statement at all probable."

A crystal lens had been found in the treasure-house at Nineveh.

In many of the temples and treasure houses of old civilizations upon this earth have been preserved things that have fallen from the sky—or meteorites.

Again we have a Brahmin. This thing is buried alive in the heart of propriety: it is in the British Museum.

Carpenter, in The Microscope and Its Revelations, gives two drawings of it. Carpenter argues that it is impossible to accept that optical lenses had ever been made by the ancients. Never occurred to him—someone a million miles or so up in the air—looking through his telescope—lens drops out.

This does not appeal to Carpenter: he says that this object must have been an ornament.

According to Brewster, it was not an ornament, but "a true optical lens."

In that case, in ruins of an old civilization upon this earth, has been found an accursed thing that was, acceptably, not a product of any old civilization indigenous to this earth.

10Early explorers have Florida mixed up with Newfoundland. But the confusion is worse than that still earlier. It arises from simplicity. Very early explorers think that all land westward is one land, India: awareness of other lands as well as India comes as a slow process. I do not now think of things arriving upon this earth from some especial other world. That was my notion when I started to collect our data. Or, as is a commonplace of observation, all intellection begins with the illusion of homogeneity. It's one of Spencer's data: we see homogeneousness in all things distant, or with which we have small acquaintance. Advance from the relatively homogeneous to the relatively heterogeneous is Spencerian Philosophy—like everything else, so-called: not that it was really Spencer's discovery, but was taken from von Baer, who, in turn, was continuous with preceding evolutionary speculation. Our own expression is that all things are acting to advance to the homogeneous, or are trying to localize Homogeneousness. Homogeneousness is an aspect of the Universal, wherein it is a state that does not merge away into something else. We regard homogeneousness as an aspect of positiveness, but it is our acceptance that infinite frustrations of attempts to positivize manifest themselves in infinite heterogeneity: so that though things try to localize homogeneousness they end up in heterogeneity so great that it amounts to infinite dispersion or indistinguishability.

So all concepts are little attempted positivenesses, but soon have to give in to compromise, modification, nullification, merging away into indistinguishability—unless, here and there, in the world's history, there may have been a super-dogmatist, who, for only an infinitesimal of time, has been able to hold out against heterogeneity or modification or doubt or "listening to reason," or loss of identity—in which case—instant translation to heaven or the Positive Absolute.

Odd thing about Spencer is that he never recognized that "homogeneity," "integration," and "definiteness" are all words for the same state, or the state that we call "positiveness." What we call his mistake is in that he regarded "homogeneousness" as negative.

I began with a notion of some one other world, from which objects and substances have fallen to this earth; which had, or which, to less degree, has a tutelary interest in this earth; which is now attempting to communicate with this earth—modifying, because of data which will pile up later, into acceptance that some other world is not attempting but has been, for centuries, in communication with a sect, perhaps, or a secret society, or certain esoteric ones of this earth's inhabitants.

I lose a great deal of hypnotic power in not being able to concentrate attention upon some one other world.

As I have admitted before I'm intelligent, as contrasted with the orthodox. I haven't the aristocratic disregard of a New York curator or an Eskimo medicine-man.

I have to dissipate myself in acceptance of a host of other worlds: size of the moon, some of them: one of them, at least—tremendous thing: we'll take that up later. Vast, amorphous aerial regions, to which such definite words as "worlds" and "planets" seem inapplicable. And artificial constructions that I have called "super-constructions": one of them about the size of Brooklyn, I should say, offhand. And one or more of them wheel-shaped things a goodly number of square miles in area.

I think that earlier in this book, before we liberalized into embracing everything that comes along, your indignation, or indigestion would have expressed in the notion that, if this were so, astronomers would have seen these other worlds and regions and vast geometric constructions. You'd have had that notion: you'd have stopped there.

But the attempt to stop is saying "enough" to the insatiable. In cosmic punctuation there are no periods: illusion of periods is incomplete view of colons and semi-colons.

We can't stop with the notion that if there were such phenomena, astronomers would have seen them. Because of our experience with suppression and disregard, we suspect, before we go into the subject at all, that astronomers have seen them; that navigators and meteorologists have seen them; that individual scientists and other trained observers have seen them many times—

That it is the System that has excluded data of them.

As to the Law of Gravitation, and astronomers' formulas, remember that these formulas worked out in the time of Laplace as well as they do now. But there are hundreds of planetary bodies now known that were then not known. So a few hundred worlds more of ours won't make any difference. Laplace knew of about only thirty bodies in this solar system: about six hundred are recognized now—

What are the discoveries of geology and biology to a theologian?

His formulas still work out as well as they ever did.

If the Law of Gravitation could be stated as a real utterance, it might be a real resistance to us. But we are told only that gravitation is gravitation. Of course to an intermediatist, nothing can be defined except in terms of itself—but even the orthodox, in what seems to me to be the innate premonitions of realness, not founded upon experience, agree that to define a thing in terms of itself is not real definition. It is said that by gravitation is meant the attraction of all things proportionately to mass and inversely as the square of the distance. Mass would mean inter-attraction holding together final particles, if there were final particles. Then, until final particles be discovered, only one term of this expression survives, or mass is attraction. But distance is only extent of mass, unless one holds out for absolute vacuum among planets, a position against which we could bring a host of data. But there is no possible means of expressing that gravitation is anything other than attraction. So there is nothing to resist us but such a phantom as—that gravitation is the gravitation of all gravitations proportionately to gravitation and inversely as the square of gravitation. In a quasi-existence,

Comments (0)