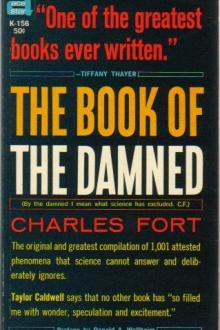

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

Butter and paper and wool and silk and resin.

We see, to start with, that the virgins of science have fought and wept and screamed against external relations—upon two grounds:

There in the first place;

Or up from one part of this earth's surface and down to another.

As late as November, 1902, in Nature Notes, 13-231, a member of the Selborne Society still argued that meteorites do not fall from the sky; that they are masses of iron upon the ground "in the first place," that attract lightning; that the lightning is seen, and is mistaken for a falling, luminous object—

By progress we mean rape.

Butter and beef and blood and a stone with strange inscriptions upon it.

3So then, it is our expression that Science relates to real knowledge no more than does the growth of a plant, or the organization of a department store, or the development of a nation: that all are assimilative, or organizing, or systematizing processes that represent different attempts to attain the positive state—the state commonly called heaven, I suppose I mean.

There can be no real science where there are indeterminate variables, but every variable is, in finer terms, indeterminate, or irregular, if only to have the appearance of being in Intermediateness is to express regularity unattained. The invariable, or the real and stable, would be nothing at all in Intermediateness—rather as, but in relative terms, an undistorted interpretation of external sounds in the mind of a dreamer could not continue to exist in a dreaming mind, because that touch of relative realness would be of awakening and not of dreaming. Science is the attempt to awaken to realness, wherein it is attempt to find regularity and uniformity. Or the regular and uniform would be that which has nothing external to disturb it. By the universal we mean the real. Or the notion is that the underlying super-attempt, as expressed in Science, is indifferent to the subject-matter of Science: that the attempt to regularize is the vital spirit. Bugs and stars and chemical messes: that they are only quasi-real, and that of them there is nothing real to know; but that systematization of pseudo-data is approximation to realness or final awakening—

Or a dreaming mind—and its centaurs and canary birds that turn into giraffes—there could be no real biology upon such subjects, but attempt, in a dreaming mind, to systematize such appearances would be movement toward awakening—if better mental co-ordination is all that we mean by the state of being awake—relatively awake.

So it is, that having attempted to systematize, by ignoring externality to the greatest possible degree, the notion of things dropping in upon this earth, from externality, is as unsettling and as unwelcome to Science as—tin horns blowing in upon a musician's relatively symmetric composition—flies alighting upon a painter's attempted harmony, and tracking colors one into another—suffragist getting up and making a political speech at a prayer meeting.

If all things are of a oneness, which is a state intermediate to unrealness and realness, and if nothing has succeeded in breaking away and establishing entity for itself, and could not continue to "exist" in intermediateness, if it should succeed, any more than could the born still at the same time be the uterine, I of course know of no positive difference between Science and Christian Science—and the attitude of both toward the unwelcome is the same—"it does not exist."

A Lord Kelvin and a Mrs. Eddy, and something not to their liking—it does not exist.

Of course not, we Intermediates say: but, also, that, in Intermediateness, neither is there absolute non-existence.

Or a Christian Scientist and a toothache—neither exists in the final sense: also neither is absolutely non-existent, and, according to our therapeutics, the one that more highly approximates to realness will win.

A secret of power—

I think it's another profundity.

Do you want power over something?

Be more nearly real than it.

We'll begin with yellow substances that have fallen upon this earth: we'll see whether our data of them have a higher approximation to realness than have the dogmas of those who deny their existence—that is, as products from somewhere external to this earth.

In mere impressionism we take our stand. We have no positive tests nor standards. Realism in art: realism in science—they pass away. In 1859, the thing to do was to accept Darwinism; now many biologists are revolting and trying to conceive of something else. The thing to do was to accept it in its day, but Darwinism of course was never proved:

The fittest survive.

What is meant by the fittest?

Not the strongest; not the cleverest—

Weakness and stupidity everywhere survive.

There is no way of determining fitness except in that a thing does survive.

"Fitness," then, is only another name for "survival."

Darwinism:

That survivors survive.

Although Darwinism, then, seems positively baseless, or absolutely irrational, its massing of supposed data, and its attempted coherence approximate more highly to Organization and Consistency than did the inchoate speculations that preceded it.

Or that Columbus never proved that the earth is round.

Shadow of the earth on the moon?

No one has ever seen it in its entirety. The earth's shadow is much larger than the moon. If the periphery of the shadow is curved—but the convex moon—a straight-edged object will cast a curved shadow upon a surface that is convex.

All the other so-called proofs may be taken up in the same way. It was impossible for Columbus to prove that the earth is round. It was not required: only that with a higher seeming of positiveness than that of his opponents, he should attempt. The thing to do, in 1492, was nevertheless to accept that beyond Europe, to the west, were other lands.

I offer for acceptance, as something concordant with the spirit of this first quarter of the 20th century, the expression that beyond this earth are—other lands—from which come things as, from America, float things to Europe.

As to yellow substances that have fallen upon this earth, the endeavor to exclude extra-mundane origins is the dogma that all yellow rains and yellow snows are colored with pollen from this earth's pine trees. Symons' Meteorological Magazine is especially prudish in this respect and regards as highly improper all advances made by other explainers.

Nevertheless, the Monthly Weather Review, May, 1877, reports a golden-yellow fall, of Feb. 27, 1877, at Peckloh, Germany, in which four kinds of organisms, not pollen, were the coloring matter. There were minute things shaped like arrows, coffee beans, horns, and disks.

They may have been symbols. They may have been objective hieroglyphics—

Mere passing fancy—let it go—

In the Annales de Chimie, 85-288, there is a list of rains said to have contained sulphur. I have thirty or forty other notes. I'll not use one of them. I'll admit that every one of them is upon a fall of pollen. I said, to begin with, that our methods would be the methods of theologians and scientists, and they always begin with an appearance of liberality. I grant thirty or forty points to start with. I'm as liberal as any of them—or that my liberality won't cost me anything—the enormousness of the data that we shall have.

Or just to look over a typical instance of this dogma, and the way it works out:

In the American Journal of Science, 1-42-196, we are told of a yellow substance that fell by the bucketful upon a vessel, one "windless" night in June, in Pictou Harbor, Nova Scotia. The writer analyzed the substance, and it was found to "give off nitrogen and ammonia and an animal odor."

Now, one of our Intermediatist principles, to start with, is that so far from positive, in the aspect of Homogeneousness, are all substances, that, at least in what is called an elementary sense, anything can be found anywhere. Mahogany logs on the coast of Greenland; bugs of a valley on the top of Mt. Blanc; atheists at a prayer meeting; ice in India. For instance, chemical analysis can reveal that almost any dead man was poisoned with arsenic, we'll say, because there is no stomach without some iron, lead, tin, gold, arsenic in it and of it—which, of course, in a broader sense, doesn't matter much, because a certain number of persons must, as a restraining influence, be executed for murder every year; and, if detectives aren't able really to detect anything, illusion of their success is all that is necessary, and it is very honorable to give up one's life for society as a whole.

The chemist who analyzed the substance of Pictou sent a sample to the Editor of the Journal. The Editor of course found pollen in it.

My own acceptance is that there'd have to be some pollen in it: that nothing could very well fall through the air, in June, near the pine forests of Nova Scotia, and escape all floating spores of pollen. But the Editor does not say that this substance "contained" pollen. He disregards "nitrogen, ammonia, and an animal odor," and says that the substance was pollen. For the sake of our thirty or forty tokens of liberality, or pseudo-liberality, if we can't be really liberal, we grant that the chemist of the first examination probably wouldn't know an animal odor if he were janitor of a menagerie. As we go along, however, there can be no such sweeping ignoring of this phenomenon:

The fall of animal-matter from the sky.

I'd suggest, to start with, that we'd put ourselves in the place of deep-sea fishes:

How would they account for the fall of animal-matter from above?

They wouldn't try—

Or it's easy enough to think of most of us as deep-sea fishes of a kind.

Jour. Franklin Inst., 90-11:

That, upon the 14th of February, 1870, there fell, at Genoa, Italy, according to Director Boccardo, of the Technical Institute of Genoa, and Prof. Castellani, a yellow substance. But the microscope revealed numerous globules of cobalt blue, also corpuscles of a pearly color that resembled starch. See Nature, 2-166.

Comptes Rendus, 56-972:

M. Bouis says of a substance, reddish varying to yellowish, that fell enormously and successively, or upon April 30, May 1 and May 2, in France and Spain, that it carbonized and spread the odor of charred animal matter—that it was not pollen—that in alcohol it left a residue of resinous matter.

Hundreds of thousands of tons of this matter must have fallen.

"Odor of charred animal matter."

Or an aerial battle that occurred in inter-planetary space several hundred years ago—effect of time in making diverse remains uniform in appearance—

It's all very absurd because, even though we are told of a prodigious quantity of animal matter that fell from the sky—three days—France and Spain—we're not ready yet: that's all. M. Bouis says that this substance was not pollen; the vastness of the fall makes acceptable that it was not pollen; still, the resinous residue does suggest pollen of pine trees. We shall hear a great deal of a substance with a resinous residue that has fallen from the sky: finally we shall divorce it from all suggestion of pollen.

Blackwood's Magazine, 3-338:

A yellow powder that fell at Gerace, Calabria, March 14, 1813. Some of this substance was collected by Sig. Simenini, Professor of Chemistry, at Naples. It had an earthy, insipid taste, and is described as "unctuous." When heated, this matter turned brown, then black, then red. According to the Annals of Philosophy, 11-466, one of the components was a greenish-yellow substance, which, when dried, was found to be resinous.

But concomitants of this fall:

Loud noises were heard in the sky.

Stones fell from the sky.

According to Chladni, these concomitants occurred, and to me they seem—rather brutal?—or not associable with something so soft and gentle as a fall of pollen?

Black rains and black snows—rains as black as a deluge of ink—jet-black snowflakes.

Such a rain as that which fell in Ireland, May 14, 1849, described in the Annals of Scientific Discovery, 1850, and the Annual Register, 1849. It fell upon a district of 400 square miles, and was the color of ink, and of a fetid odor and very disagreeable taste.

The rain at Castlecommon, Ireland, April 30, 1887—"thick, black rain." (Amer. Met. Jour., 4-193.)

A black

Comments (0)