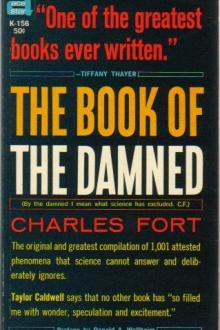

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

Nature, 7-112:

That, according to a correspondent to the Birmingham Morning News, the people living near King's Sutton, Banbury, saw, about one o'clock, Dec. 7, 1872, something like a haycock hurtling through the air. Like a meteor it was accompanied by fire and a dense smoke and made a noise like that of a railway train. "It was sometimes high in the air and sometimes near the ground." The effect was tornado-like: trees and walls were knocked down. It's a late day now to try to verify this story, but a list is given of persons whose property was injured. We are told that this thing then disappeared "all at once."

These are the smaller objects, which may be derailed railway trains or big green snakes, for all I know—but our expression upon approach to this earth by vast dark bodies—

That likely they'd be made luminous: would envelop in clouds, perhaps, or would have their own clouds—

But that they'd quake, and that they'd affect this earth with quakes—

And that then would occur a fall of matter from such a world, or rise of matter from this earth to a nearby world, or both fall and rise, or exchange of matter—process known to Advanced Seismology as celestio-metathesis—

Except that—if matter from some other world—and it would be like someone to get it into his head that we absolutely deny gravitation, just because we cannot accept orthodox dogmas—except that, if matter from another world, filling the sky of this earth, generally, as to a hemisphere, or locally, should be attracted to this earth, it would seem thinkable that the whole thing should drop here, and not merely its surface-materials.

Objects upon a ship's bottom. From time to time they drop to the bottom of the ocean. The ship does not.

Or, like our acceptance upon dripping from aerial ice-fields, we think of only a part of a nearby world succumbing, except in being caught in suspension, to this earth's gravitation, and surface-materials falling from that part—

Explain or express or accept, and what does it matter? Our attitude is:

Here are the data.

See for yourself.

What does it matter what my notions may be?

Here are the data.

But think for yourself, or think for myself, all mixed up we must be. A long time must go by before we can know Florida from Long Island. So we've had data of fishes that have fallen from our now established and respectabilized Super-Sargasso Sea—which we've almost forgotten, it's now so respectable—but we shall have data of fishes that have fallen during earthquakes. These we accept were dragged down from ponds or other worlds that have been quaked, when only a few miles away, by this earth, some other world also quaking this earth.

In a way, or in its principle, our subject is orthodox enough. Only grant proximity of other worlds—which, however, will not be a matter of granting, but will be a matter of data—and one conventionally conceives of their surfaces quaked—even of a whole lake full of fishes being quaked and dragged down from one of them. The lake full of fishes may cause a little pain to some minds, but the fall of sand and stones is pleasantly enough thought of. More scientific persons, or more faithful hypnotics than we, have taken up this subject, unpainfully, relatively to the moon. For instance, Perrey has gone over 15,000 records of earthquakes, and he has correlated many with proximities of the moon, or has attributed many to the pull of the moon when nearest this earth. Also there is a paper upon this subject in the Proc. Roy. Soc. of Cornwall, 1845. Or, theoretically, when at its closest to this earth, the moon quakes the face of this earth, and is itself quaked—but does not itself fall to this earth. As to showers of matter that may have come from the moon at such times—one can go over old records and find what one pleases.

That is what we now shall do.

Our expressions are for acceptance only.

Our data:

We take them from four classes of phenomena that have preceded or accompanied earthquakes:

Unusual clouds, darkness profound, luminous appearances in the sky, and falls of substances and objects whether commonly called meteoritic or not.

Not one of these occurrences fits in with principles of primitive, or primary, seismology, and every one of them is a datum of a quaked body passing close to this earth or suspended over it. To the primitives there is not a reason in the world why a convulsion of this earth's surface should be accompanied by unusual sights in the sky, by darkness, or by the fall of substances or objects from the sky. As to phenomena like these, or storms, preceding earthquakes, the irreconcilability is still greater.

It was before 1860 that Perrey made his great compilation. We take most of our data from lists compiled long ago. Only the safe and unpainful have been published in recent years—at least in ambitious, voluminous form. The restraining hand of the "System"—as we call it, whether it has any real existence or not—is tight upon the sciences of today. The uncanniest aspect of our quasi-existence that I know of is that everything that seems to have one identity has also as high a seeming of everything else. In this oneness of allness, or continuity, the protecting hand strangles; the parental stifles; love is inseparable from phenomena of hate. There is only Continuity—that is in quasi-existence. Nature, at least in its correspondents' columns, still evades this protective strangulation, and the Monthly Weather Review is still a rich field of unfaithful observation: but, in looking over other long-established periodicals, I have noted their glimmers of quasi-individuality fade gradually, after about 1860, and the surrender of their attempted identities to a higher attempted organization. Some of them, expressing Intermediateness-wide endeavor to localize the universal, or to localize self, soul, identity, entity—or positiveness or realness—held out until as far as 1880; traces findable up to 1890—and then, expressing the universal process—except that here and there in the world's history there may have been successful approximations to positiveness by "individuals"—who only then became individuals and attained to selves or souls of their own—surrendered, submitted, became parts of a higher organization's attempt to individualize or systematize into a complete thing, or to localize the universal or the attributes of the universal. After the death of Richard Proctor, whose occasional illiberalities I'd not like to emphasize too much, all succeeding volumes of Knowledge have yielded scarcely an unconventionality. Note the great number of times that the American Journal of Science and the Report of the British Association are quoted: note that, after, say, 1885, they're scarcely mentioned in these inspired but illicit pages—as by hypnosis and inertia, we keep on saying.

About 1880.

Throttle and disregard.

But the coercion could not be positive, and many of the excommunicated continued to creep in; or, even to this day, some of the strangled are faintly breathing.

Some of our data have been hard to find. We could tell stories of great labor and fruitless quests that would, though perhaps imperceptibly, stir the sympathy of a Mr. Symons. But, in this matter of concurrence of earthquakes with aerial phenomena, which are as unassociable with earthquakes, if internally caused, as falls of sand on convulsed small boys full of sour apples, the abundance of so-called evidence is so great that we can only sketchily go over the data, beginning with Robert Mallet's Catalogue (Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1852), omitting some extraordinary instances, because they occurred before the eighteenth century:

Earthquake "preceded" by a violent tempest, England, Jan. 8, 1704—"preceded" by a brilliant meteor, Switzerland, Nov. 4, 1704—"luminous cloud, moving at high velocity, disappearing behind the horizon," Florence, Dec. 9, 1731—"thick mists in the air, through which a dim light was seen: several weeks before the shock, globes of light had been seen in the air," Swabia, May 22, 1732—rain of earth, Carpentras, France, Oct. 18, 1737—a black cloud, London, March 19, 1750—violent storm and a strange star of octagonal shape, Slavange, Norway, April 15, 1752—balls of fire from a streak in the sky, Augermannland, 1752—numerous meteorites, Lisbon, Oct. 15, 1755—"terrible tempests" over and over—"falls of hail" and "brilliant meteors," instance after instance—"an immense globe," Switzerland, Nov. 2, 1761—oblong, sulphurous cloud, Germany, April, 1767—extraordinary mass of vapor, Boulogne, April, 1780—heavens obscured by a dark mist, Grenada, Aug. 7, 1804—"strange, howling noises in the air, and large spots obscuring the sun," Palermo, Italy, April 16, 1817—"luminous meteor moving in the same direction as the shock," Naples, Nov. 22, 1821—fire ball appearing in the sky: apparent size of the moon, Thuringerwald, Nov. 29, 1831.

And, unless you be polarized by the New Dominant, which is calling for recognition of multiplicities of external things, as a Dominant, dawning new over Europe in 1492, called for recognition of terrestrial externality to Europe—unless you have this contact with the new, you have no affinity for these data—beans that drop from a magnet—irreconcilables that glide from the mind of a Thomson—

Or my own acceptance that we do not really think at all; that we correlate around super-magnets that I call Dominants—a Spiritual Dominant in one age, and responsively to it up spring monasteries, and the stake and the cross are its symbols: a Materialist Dominant, and up spring laboratories, and microscopes and telescopes and crucibles are its ikons—that we're nothing but iron filings relatively to a succession of magnets that displace preceding magnets.

With no soul of your own, and with no soul of my own—except that some day some of us may no longer be Intermediatisms, but may hold out against the cosmos that once upon a time thousands of fishes were cast from one pail of water—we have psycho-valency for these data, if we're obedient slaves to the New Dominant, and repulsion to them, if we're mere correlates to the Old Dominant. I'm a soulless and selfless correlate to the New Dominant, myself: I see what I have to see. The only inducement I can hold out, in my attempt to rake up disciples, is that some day the New will be fashionable: the new correlates will sneer at the old correlates. After all, there is some inducement to that—and I'm not altogether sure it's desirable to end up as a fixed star.

As a correlate to the New Dominant, I am very much impressed with some of these data—the luminous object that moved in the same direction as an earthquake—it seems very acceptable that a quake followed this thing as it passed near this earth's surface. The streak that was seen in the sky—or only a streak that was visible of another world—and objects, or meteorites, that were shaken down from it. The quake at Carpentras, France: and that, above Carpentras, was a smaller world, more violently quaked, so that earth was shaken down from it.

But I like best the super-wolves that were seen to cross the sun during the earthquake at Palermo.

They howled.

Or the loves of the worlds. The call they feel for one another. They try to move closer and howl when they get there.

The howls of the planets.

I have discovered a new unintelligibility.

In the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal—have to go away back to 1841—days of less efficient strangulation—Sir David Milne lists phenomena of quakes in Great Britain. I pick out a few that indicate to me that other worlds were near this earth's surface:

Violent storm before a shock of 1703—ball of fire "preceding," 1750—a large ball of fire seen upon day following a quake, 1755—"uncommon phenomenon in the air: a large luminous body, bent like a crescent, which stretched itself over the heavens, 1816—vast ball of fire, 1750—black rains and black snows, 1755—numerous instances of upward projection—or upward attraction?—during quakes—preceded by a cloud, very black and lowering," 1795—fall of black powder, preceding a quake, by six hours, 1837.

Some of these instances seem to me to be very striking—a smaller world: it is greatly racked by the attraction of this

Comments (0)