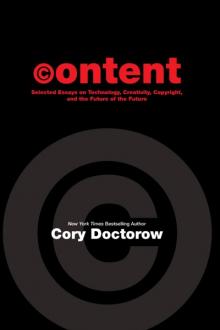

Content, Cory Doctorow [free romance novels .TXT] 📗

- Author: Cory Doctorow

- Performer: 1892391813

Book online «Content, Cory Doctorow [free romance novels .TXT] 📗». Author Cory Doctorow

I started attending DRM meetings in March, 2002, on behalf of my former employers, the Electronic Frontier Foundation. My first meeting was the one where Broadcast Flag was born. The Broadcast Flag was weird even by DRM standards. Broadcasters are required, by law, to deliver TV and radio without DRM, so that any standards-compliant receiver can receive them. The airwaves belong to the public, and are loaned to broadcasters who have to promise to serve the public interest in exchange. But the MPAA and the broadcasters wanted to add DRM to digital TV, and so they proposed that a law should be passed that would make all manufacturers promise to pretend that there was DRM on broadcast signals, receiving them and immediately squirreling them away in encrypted form.

The Broadcast Flag was hammered out in a group called the Broadcast Protection Discussion Group (BPDG) a sub-group from the MPAA’s “Content Protection Technology Working Group,” which also included reps from all the big IT companies (Microsoft, Apple, Intel, and so on), consumer electronics companies (Panasonic, Philips, Zenith), cable companies, satellite companies, and anyone else who wanted to pay $100 to attend the “public” meetings, held every six weeks or so (you can attend these meetings yourself if you find yourself near LAX on one of the upcoming dates).

CPTWG (pronounced Cee-Pee-Twig) is a venerable presence in the DRM world. It was at CPTWG that the DRM for DVDs was hammered out. CPTWG meetings open with a “benediction,” delivered by a lawyer, who reminds everyone there that what they say might be quoted “on the front page of the New York Times,” (though journalists are barred from attending CPTWG meetings and no minutes are published by the organization) and reminding all present not to do anything that would raise eyebrows at the FTC’s anti-trust division (I could swear I’ve seen the Microsoft people giggling during this part, though that may have been my imagination).

The first part of the meeting is usually taken up with administrative business and presentations from DRM vendors, who come out to promise that this time they’ve really, really figured out how to make computers worse at copying. The real meat comes after the lunch, when the group splits into a series of smaller meetings, many of them closed-door and private (the representatives of the organizations responsible for managing DRM on DVDs splinter off at this point).

Then comes the working group meetings, like the BPDG. The BPDG was nominally set up to set up the rules for the Broadcast Flag. Under the Flag, manufacturers would be required to limit their “outputs and recording methods” to a set of “approved technologies.” Naturally, every manufacturer in the room showed up with a technology to add to the list of approved technologies — and the sneakier ones showed up with reasons why their competitors’ technologies shouldn’t be approved. If the Broadcast Flag became law, a spot on the “approved technologies” list would be a license to print money: everyone who built a next-gen digital TV would be required, by law, to buy only approved technologies for their gear.

The CPTWG determined that there would be three “chairmen” of the meetings: a representative from the broadcasters, a representative from the studios, and a representative from the IT industry (note that no “consumer rights” chair was contemplated — we proposed one and got laughed off the agenda). The IT chair was filled by an Intel representative, who seemed pleased that the MPAA chair, Fox Studios’s Andy Setos, began the process by proposing that the approved technologies should include only two technologies, both of which Intel partially owned.

Intel’s presence on the committee was both reassurance and threat: reassurance because Intel signaled the fundamental reasonableness of the MPAA’s requirements — why would a company with a bigger turnover than the whole movie industry show up if the negotiations weren’t worth having? Threat because Intel was poised to gain an advantage that might be denied to its competitors.

We settled in for a long negotiation. The discussions were drawn out and heated. At regular intervals, the MPAA reps told us that we were wasting time — if we didn’t hurry things along, the world would move on and consumers would grow accustomed to un-crippled digital TVs. Moreover, Rep Billy Tauzin, the lawmaker who’d evidently promised to enact the Broadcast Flag into law, was growing impatient. The warnings were delivered in quackspeak, urgent and crackling, whenever the discussions dragged, like the crack of the commissars’ pistols, urging us forward.

You’d think that a “technology working group” would concern itself with technology, but there was precious little discussion of bits and bytes, ciphers and keys. Instead, we focused on what amounted to contractual terms: if your technology got approved as a DTV “output,” what obligations would you have to assume? If a TiVo could serve as an “output” for a receiver, what outputs would the TiVo be allowed to have?

The longer we sat there, the more snarled these contractual terms became: winning a coveted spot on the “approved technology” list would be quite a burden! Once you were in the club, there were all sorts of rules about whom you could associate with, how you had to comport yourself and so on.

One of these rules of conduct was “robustness.” As a condition of approval, manufacturers would have to harden their technologies so that their customers wouldn’t be able to modify, improve upon, or even understand their workings. As you might imagine, the people who made open source TV tuners were not thrilled about this, as “open source” and “non-user-modifiable” are polar opposites.

Another was “renewability:” the ability of the studios to revoke outputs that had been compromised in the field. The studios expected the manufacturers to make products with remote “kill switches” that could be used to shut down part or all of their device if someone, somewhere had figured out how to do something naughty with it. They promised that we’d establish criteria for renewability later, and that it would all be “fair.”

But we soldiered on. The MPAA had a gift for resolving the worst snarls: when shouting failed, they’d lead any recalcitrant player out of the room and negotiate in secret with them, leaving the rest of us to cool our heels. Once, they took the Microsoft team out of the room for six hours, then came back and announced that digital video would be allowed to output on non-DRM monitors at a greatly reduced resolution (this “feature” appears in Vista as “fuzzing”).

The further we went, the more nervous everyone became. We were headed for the real meat of the negotiations: the criteria by which approved technology would be evaluated: how many bits of crypto would you need? Which ciphers would be permissible? Which features would and wouldn’t be allowed?

Then the MPAA dropped the other shoe: the sole criteria for inclusion on the list would be the approval of one of its member-companies, or a quorum of broadcasters. In other words, the Broadcast Flag wouldn’t be an “objective standard,” describing the technical means by which video would be locked away — it would be purely subjective, up to the whim of the studios. You could have the best product in the world, and they wouldn’t approve it if your business-development guys hadn’t bought enough drinks for their business-development guys at a CES party.

To add insult to injury, the only technologies that the MPAA were willing to consider for initial inclusion as “approved” were the two that Intel was involved with. The Intel co-chairman had a hard time hiding his grin. He’d acted as Judas goat, luring in Apple, Microsoft, and the rest, to legitimize a process that would force them to license Intel’s patents for every TV technology they shipped until the end of time.

Why did the MPAA give Intel such a sweetheart deal? At the time, I figured that this was just straight quid pro quo, like Hannibal said to Clarice. But over the years, I started to see a larger pattern: Hollywood likes DRM consortia, and they hate individual DRM vendors. (I’ve written an entire article about this, but here’s the gist: a single vendor who succeeds can name their price and terms — think of Apple or Macrovision — while a consortium is a more easily divided rabble, susceptible to co-option in order to produce ever-worsening technologies — think of Blu-Ray and HD-DVD). Intel’s technologies were held through two consortia, the 5C and 4C groups.

The single-vendor manufacturers were livid at being locked out of the digital TV market. The final report of the consortium reflected this — a few sheets written by the chairmen describing the “consensus” and hundreds of pages of angry invective from manufacturers and consumer groups decrying it as a sham.

Tauzin washed his hands of the process: a canny, sleazy Hill operator, he had the political instincts to get his name off any proposal that could be shown to be a plot to break voters’ televisions (Tauzin found a better industry to shill for, the pharmaceutical firms, who rewarded him with a $2,000,000/year job as chief of PHARMA, the pharmaceutical lobby).

Even Representative Ernest “Fritz” Hollings (“The Senator from Disney,” who once proposed a bill requiring entertainment industry oversight of all technologies capable of copying) backed away from proposing a bill that would turn the Broadcast Flag into law. Instead, Hollings sent a memo to Michael Powell, then-head of the FCC, telling him that the FCC already had jurisdiction to enact a Broadcast Flag regulation, without Congressional oversight.

Powell’s staff put Hollings’s letter online, as they are required to do by federal sunshine laws. The memo arrived as a Microsoft Word file — which EFF then downloaded and analyzed. Word stashes the identity of a document’s author in the file metadata, which is how EFF discovered that the document had been written by a staffer at the MPAA.

This was truly remarkable. Hollings was a powerful committee chairman, one who had taken immense sums of money from the industries he was supposed to be regulating. It’s easy to be cynical about this kind of thing, but it’s genuinely unforgivable: politicians draw a public salary to sit in public office and work for the public good. They’re supposed to be working for us, not their donors.

But we all know that this isn’t true. Politicians are happy to give special favors to their pals in industry. However, the Hollings memo was beyond the pale. Staffers for the MPAA were writing Hollings’s memos, memos that Hollings then signed and mailed off to the heads of major governmental agencies.

The best part was that the legal eagles at the MPAA were wrong. The FCC took “Hollings’s” advice and enacted a Broadcast Flag regulation that was almost identical to the proposal from the BPDG, turning themselves into America’s “device czars,” able to burden any digital technology with “robustness,” “compliance” and “revocation rules.” The rule lasted just long enough for the DC Circuit Court of Appeals to strike it down and slap the FCC for grabbing unprecedented jurisdiction over the devices in our living rooms.

So ended the saga of the Broadcast Flag. More or less. In the years since the Flag was proposed, there have been several attempts to reintroduce it through legislation, all failed. And as more and more innovative, open devices like the Neuros OSD enter the market, it gets harder and harder to imagine that Americans will accept a mandate that takes away all that functionality.

But the spirit of the Broadcast Flag lives on. DRM consortia are all the rage now — outfits like AACS LA, the folks who control the DRM in Blu-Ray and HD-DVD, are thriving and making headlines by issuing fatwas against people who publish their secret integers. In Europe, a DRM consortium working under the auspices of the

Comments (0)