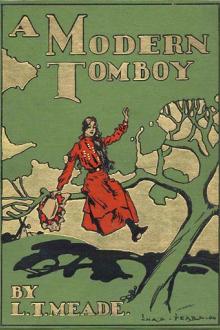

A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Book online «A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

"Don't speak of it now, dear Cartery. It always upsets you, doesn't it? Let us talk of something else. You are very happy with us, aren't you, Cartery love?"

"Cartery love" expressed that she was, and Maud slipped her hand affectionately through her governess's arm.

Rosamund gave the latter lady a keen glance. She saw that she was naturally extremely kind, but also shy and wanting in courage.

"She could never master Irene," thought the girl. "Irene is going to be given to me. She shall be mine. I mean to help her. I mean, whatever happens, to save her. But I don't mind talking a wee little bit about her to 'Cartery love,' as that funny Maud calls her."

The rest of the girls came up in a group, and the next hour or two were spent wandering through the pleasant gardens, while laughter, jokes, and good-humored chatter of all sorts filled the air.

Then came tea. Now, the rector's teas were celebrated. They were, in fact, that old-fashioned institution, now, alas! so rapidly disappearing from our English life, known as "high tea." Eggs, boiled ham, chickens, stewed fruits, fresh ripe fruit of every sort and variety, graced the board. No dinner followed this meal; but sandwiches and lemonade generally concluded the happy day.

The girls knew that they were not expected back until bedtime, and gave themselves absolutely up to the pleasures of the time. The Rectory was a charming old house, being quite a hundred and fifty or two hundred years old; and the study, or schoolroom, as the girls called it, where they invariably partook of tea, was a low-roofed apartment running right across the eastern side of the house. It was, therefore, at this hour a delightfully cool room, and was rendered more so by the bowery shade of green trees.

Rosamund found herself sitting near Maud at the meal, and she suddenly turned to her and said, "I quite understand now why you wear green, and why some people call you the Leaves."

"One person, you mean," said Maud, coloring slightly.

Lucy gave Rosamund an angry glance, and even managed to kick her under the table. This kick was highly resented by that young person, who, as she said to herself, stiffened her neck on the spot and determined to show what mettle she was made of.

"I'm not going to be mastered by that horrid Lucy, come what may," she thought.

Although it was impossible to be absolutely rude to Maud, who was one of those charming girls, unaffected, affectionate, and natural, who must delight every one, yet Rosamund's real object was to have a talk with "Cartery love." Now, Cartery's hands were full at that moment, for she was absorbed pouring out coffee at the other end of the table, never thinking once of herself, attending to the wants of every one else. She was one of those retiring people who may come and go in a crowd without any one specially noticing them; but if a kind office is wanted to be done in the most unobtrusive and gentle way, then "Cartery love" was sure to be at the fore. On this occasion she did glance once or twice at Rosamund, and something which was not often seen in her eyes filled them for a moment—a look of mingled admiration and fear. Rosamund determined to bide her time.

"I have not come here to make friends with the stupid Leaves," she said to herself. "I have come here to talk to Miss Carter, and talk to her I will. The week is coming to a close, and I have to give my decision. How that decision will turn out depends as much on 'Cartery love' as on anybody else."

Tea, good as it was, came to an end at last, and the children went out into the grounds, some to play tennis, some croquet, and some to wander away, two and two, each talking, as girls will, of their hopes and fears and ambitions.

Rosamund, to whom Maud devoted herself, turned suddenly to that young person.

"I will confide in you," she said. "You are longing to play tennis, are you not?"

"Oh no, thank you, not at all," said Maud, who was one of the champion players of the neighborhood, and could never bear to be out of any game that was in progress.

"But I know you are. I can read through people pretty well," said Rosamund, speaking in a low tone. "Now, I want to have a little talk with Miss Carter. Won't you go and play, and forget all about me, and let me have a chat with Miss Carter?"

"With our darling Cartery? Why, certainly, you shall if you like. I see you want to get her to tell you about Irene. I doubt if she will. Do, please, be merciful. She is very nervous. When she came to us she was almost ill, and we had to take great, great care of her. Would you like, first of all, to know how she came to us?"

"I should very much."

Rosamund forgot at this juncture all about Maud's passionate love for tennis.

"Well, it was in this way. We had no governess; we used to go to a sort of school—not the Merrimans', for they had not started one at the time—and I used to teach the little children, and things were rather at sixes and sevens. Not that father ever minded, for he is the sort of man who just lets you do what you like, and I think that is why we have grown up nicer than most girls."

"Indeed, I didn't know it would have that effect," said Rosamund, trying to suppress the sarcastic note in her voice.

"Don't speak in that tone, please. I think we really are quite nice girls—I mean we never quarrel, and we are always chummy and affectionate, and we try to do our best. We are not a bit self-righteous or conceited, or anything of that sort; for, you see, when our dear mother was alive she taught us so beautifully. Her rule was such a very simple one. She never punished us; all she ever said was, 'Do it because it is right. You cannot quite understand why it is right while you are very young; but, nevertheless, do it because it is right and because you love me.' And when God took her, and we thought our hearts would break, we all sat in a conclave together, and we determined to follow our mother's rule, and to do the right because it was right and because we loved her. I cannot tell you what a terrible time we had; but we stuck to that resolve. Nevertheless, our education was a poor affair, although father never noticed it.

"One day I was out driving with father, and we saw a poor lady sitting by the roadside. She looked so forlorn, and her eyes were red with crying. We did not know her; but she knew us, for she stood up at once, and said to father, 'You are Mr. Singleton?'

"Then, of course, father remembered her, only I did not. She was one of the many governesses who had come to try to tame Irene Ashleigh. So father and I both got down from the gig, and she told us that she had left The Follies and was going back to London to try to get another situation. She said that she had sent on her trunks by a porter to the station, and she meant to walk, for Lady Jane was very, very angry with her. She could not go on. She broke down, poor dear! and very nearly fainted. She said she did feel very faint and bad, so we just got her into the gig—as, of course, any people who had any feelings would do—and we brought her straight back to the Rectory, and she has stayed with us ever since.

"For the first month she was not our governess at all; she was our sort of child, to be petted and loved and fussed over. We put her in the sunniest room, and when we found that her nerves were so terribly shaken that she could scarcely sleep alone, one of my sisters had a little bed made up in the room and slept with her at night. We fed her up, didn't we just? and petted her; and when we found she liked it we took to calling her 'Cartery love,' and she did not mind it a bit. Then she got better, and said she must seek another situation, and father said she should stay and teach us and look after things in the house a bit. So she stayed. She knows such a lot, and does teach us so beautifully, and she isn't half nor quarter as shy as she was; we all love her, and she loves us. I think if Irene were not so near she would be perfectly happy."

"Thank you for telling me so much," said Rosamund when Maud ceased speaking.

"I had to tell you, for I want you, if you talk to her, to be very careful, for she is still exceedingly nervous. And no wonder. What she lived through at The Follies was enough to destroy the nerves of any woman, even the stoutest-hearted in the world."

"Well, I should like to speak to her, and I will certainly not harm her," said Rosamund.

Maud left her for a little while, and in a few minutes Miss Carter was seen coming down the path with Maud hanging on her arm.

"Now, Cartery dear," she said, "you talk to Rosamund Cunliffe, who is a friend of mine, and I will go and have a good, romping game of tennis. Oh, I see they are just breaking up the present set, so I am just in time."

Off ran Maud. Miss Carter's light-blue eyes followed her with an expression of the deepest affection.

"You seem very fond of her," said Rosamund suddenly.

"I don't know what I should have done without her. She saved my life and my reason."

"I don't want to talk about what has evidently given you very great distress," said Rosamund after a time; "but I should like to tell you that I know."

"You know?" said Miss Carter, beginning to tremble, and turning very pale.

"Yes, for Irene told me."

"My dear, dear Miss Cunliffe, how had you the courage to go with her in that terrible boat? She actually took you into the current—that appalling current where one is so powerless—and you escaped!"

"Oh, yes," said Rosamund lightly. "It was a mere nothing. You see, I am stronger than she is. All she wants is management."

"I could never manage her," said Miss Carter. "I could tell you of other things she did."

"No, I don't want to hear unless you are going to tell me something nice about her. Every one seems to speak against that poor girl; but I am determined to be her friend."

"Are you really?" said Miss Carter, suddenly changing her tone and looking fixedly at Rosamund. "Then you must be about the noblest girl in the world."

These words were very gratifying to Rosamund, who did think herself rather good in taking up Irene's cause; although, of course, she was fascinated by the exceedingly naughty young person.

"Yes, indeed, you are splendid," said Miss Carter; "and I know there must be good in the child. Such courage, such animal spirits, such daring cannot be meant for nothing. The fact is, her mother cannot manage her. Her mother is too gentle, too like me."

"Dear Lady Jane! Miss Carter, when my mother was young she was her great friend, and she said that Lady Jane was rather naughty."

"Ah!" said Miss Carter, with a sigh, "she has left all that behind her a long time ago. The only time I found her hard and unsympathetic was when I told her that I could not stay any longer at The Follies. She

Comments (0)