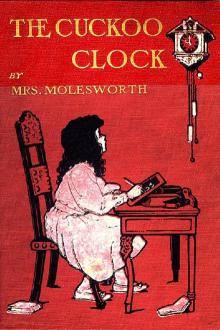

The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗

- Author: Mrs. Molesworth

- Performer: -

Book online «The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗». Author Mrs. Molesworth

"I don't know," said Griselda, dreamily. "There's a great deal to learn first, the cuckoo says."

"Have you learnt a great deal?" (he called it "a gate deal") asked Phil, looking up at Griselda with increased respect. "I don't know scarcely nothing. Mother was ill such a long time before she went away, but I know she wanted me to learn to read books. But nurse is too old to teach me."

"Shall I teach you?" said Griselda. "I can bring some of my old books and teach you here after I have done my own lessons."

"And then mother would be surprised when she comes back," said Master Phil, clapping his hands. "Oh, do. And when I've learnt to read a great deal, do you think the cuckoo would show us the way to fairyland?"

"I don't think it was that sort of learning he meant," said Griselda. "But I dare say that would help. I think," she went on, lowering her voice a little, and looking down gravely into Phil's earnest eyes, "I think he means mostly learning to be very good—very, very good, you know."

"Gooder than you?" said Phil.

"Oh dear, yes; lots and lots gooder than me," replied Griselda.

"I think you're very good," observed Phil, in a parenthesis. Then he went on with his cross-questioning.

"Gooder than mother?"

"I don't know your mother, so how can I tell how good she is?" said Griselda.

"I can tell you," said Phil, importantly. "She is just as good as—as good as—as good as good. That's what she is."

"You mean she couldn't be better," said Griselda, smiling.

"Yes, that'll do, if you like. Would that be good enough for us to be, do you think?"

"We must ask the cuckoo," said Griselda. "But I'm sure it would be a good thing for you to learn to read. You must ask your nurse to let you come here every afternoon that it's fine, and I'll ask my aunt."

"I needn't ask nurse," said Phil composedly; "she'll never know where I am, and I needn't tell her. She doesn't care what I do, except tearing my clothes; and when she scolds me, I don't care."

"That isn't good, Phil," said Griselda gravely. "You'll never be as good as good if you speak like that."

"What should I say, then? Tell me," said the little boy submissively.

"You should ask nurse to let you come to play with me, and tell her I'm much bigger than you, and I won't let you tear your clothes. And you should tell her you're very sorry you've torn them to-day."

"Very well," said Phil, "I'll say that. But, oh see!" he exclaimed, darting off, "there's a field mouse! If only I could catch him!"

Of course he couldn't catch him, nor could Griselda either; very ready, though, she was to do her best. But it was great fun all the same, and the children laughed heartily and enjoyed themselves tremendously. And when they were tired they sat down again and gathered flowers for nosegays, and Griselda was surprised to find how clever Phil was about it. He was much quicker than she at spying out the prettiest blossoms, however hidden behind tree, or stone, or shrub. And he told her of all the best places for flowers near by, and where grew the largest primroses and the sweetest violets, in a way that astonished her.

"You're such a little boy," she said; "how do you know so much about flowers?"

"I've had no one else to play with," he said innocently. "And then, you know, the fairies are so fond of them."

When Griselda thought it was time to go home, she led little Phil down the wood-path, and through the door in the wall opening on to the lane.

"Now you can find your way home without scrambling through any more bushes, can't you, Master Phil?" she said.

"Yes, thank you, and I'll come again to that place to-morrow afternoon, shall I?" asked Phil. "I'll know when—after I've had my dinner and raced three times round the big field, then it'll be time. That's how it was to-day."

"I should think it would do if you walked three times—or twice if you like—round the field. It isn't a good thing to race just when you've had your dinner," observed Griselda sagely. "And you mustn't try to come if it isn't fine, for my aunts won't let me go out if it rains even the tiniest bit. And of course you must ask your nurse's leave."

"Very well," said little Phil as he trotted off. "I'll try to remember all those things. I'm so glad you'll play with me again; and if you see the cuckoo, please thank him."

UP AND DOWN THE CHIMNEY

"Helper. Well, but if it was all dream, it would be the same as if it was all real, would it not?

Keeper. Yes, I see. I mean, Sir, I do not see."—A Liliput Revel.

ot having "just had her dinner," and feeling very much inclined for her tea, Griselda ran home at a great rate.

She felt, too, in such good spirits; it had been so delightful to have a companion in her play.

"What a good thing it was I didn't make Phil run away before I found out what a nice little boy he was," she said to herself. "I must look out my old reading books to-night. I shall so like teaching him, poor little boy, and the cuckoo will be pleased at my doing something useful, I'm sure."

Tea was quite ready, in fact waiting for her, when she came in. This was a meal she always had by herself, brought up on a tray to Dorcas's little sitting-room, where Dorcas waited upon her. And sometimes when Griselda was in a particularly good humour she would beg Dorcas to sit down and have a cup of tea with her—a liberty the old servant was far too dignified and respectful to have thought of taking, unless specially requested to do so.

This evening, as you know, Griselda was in a very particularly good humour, and besides this, so very full of her adventures, that she would have been glad of an even less sympathising listener than Dorcas was likely to be.

"Sit down, Dorcas, and have some more tea, do," she said coaxingly. "It looks ever so much more comfortable, and I'm sure you could eat a little more if you tried, whether you've had your tea in the kitchen or not. I'm fearfully hungry, I can tell you. You'll have to cut a whole lot more bread and butter and not 'ladies' slices' either."

"How your tongue does go, to be sure, Miss Griselda," said Dorcas, smiling, as she seated herself on the chair Griselda had drawn in for her.

"And why shouldn't it?" said Griselda saucily. "It doesn't do it any harm. But oh, Dorcas, I've had such fun this afternoon—really, you couldn't guess what I've been doing."

"Very likely not, missie," said Dorcas.

"But you might try to guess. Oh no, I don't think you need—guessing takes such a time, and I want to tell you. Just fancy, Dorcas, I've been playing with a little boy in the wood."

"Playing with a little boy, Miss Griselda!" exclaimed Dorcas, aghast.

"Yes, and he's coming again to-morrow, and the day after, and every day, I dare say," said Griselda. "He is such a nice little boy."

"But, missie," began Dorcas.

"Well? What's the matter? You needn't look like that—as if I had done something naughty," said Griselda sharply.

"But you'll tell your aunt, missie?"

"Of course," said Griselda, looking up fearlessly into Dorcas's face with her bright grey eyes. "Of course; why shouldn't I? I must ask her to give the little boy leave to come into our grounds; and I told the little boy to be sure to tell his nurse, who takes care of him, about his playing with me."

"His nurse," repeated Dorcas, in a tone of some relief. "Then he must be quite a little boy, perhaps Miss Grizzel would not object so much in that case."

"Why should she object at all? She might know I wouldn't want to play with a naughty rude boy," said Griselda.

"She thinks all boys rude and naughty, I'm afraid, missie," said Dorcas. "All, that is to say, excepting your dear papa. But then, of course, she had the bringing up of him in her own way from the beginning."

"Well, I'll ask her, any way," said Griselda, "and if she says I'm not to play with him, I shall think—I know what I shall think of Aunt Grizzel, whether I say it or not."

And the old look of rebellion and discontent settled down again on her rosy face.

"Be careful, missie, now do, there's a dear good girl," said Dorcas anxiously, an hour later, when Griselda, dressed as usual in her little white muslin frock, was ready to join her aunts at dessert.

But Griselda would not condescend to make any reply.

"Aunt Grizzel," she said suddenly, when she had eaten an orange and three biscuits and drunk half a glass of home-made elder-berry wine, "Aunt Grizzel, when I was out in the garden to-day—down the wood-path, I mean—I met a little boy, and he played with me, and I want to know if he may come every day to play with me."

Griselda knew she was not making her request in a very amiable or becoming manner; she knew, indeed, that she was making it in such a way as was almost certain to lead to its being refused; and yet, though she was really so very, very anxious to get leave to play with little Phil, she took a sort of spiteful pleasure in injuring her own cause.

How foolish ill-temper makes us! Griselda had allowed herself to get so angry at the thought of being thwarted that had her aunt looked up quietly and said at once, "Oh yes, you may have the little boy to play with you whenever you like," she would really, in a strange distorted sort of way, have been disappointed.

But, of course, Miss Grizzel made no such reply. Nothing less than a miracle could have made her answer Griselda otherwise than as she did. Like Dorcas, for an instant, she was utterly "flabbergasted," if you know what that means. For she was really quite an old lady, you know, and sensible as she was, things upset her much more easily than when she was younger.

Naughty Griselda saw her uneasiness, and enjoyed it.

"Playing with a boy!" exclaimed Miss Grizzel. "A boy in my grounds, and you, my niece, to have played with him!"

"Yes," said Griselda coolly, "and I want to play with him again."

"Griselda," said her aunt, "I am too astonished to say more at present. Go to bed."

"Why should I go to bed? It is not my bedtime," cried Griselda, blazing up. "What have I done to be sent to bed as if I were in disgrace?"

"Go to bed," repeated Miss Grizzel. "I will speak to you to-morrow."

"You are very unfair and unjust," said Griselda, starting up from her chair. "That's all the good of being honest and telling everything. I might have played with the little boy every day for a month and you would never have known, if I hadn't told you."

She banged across the room as she spoke, and out at the door, slamming it behind her rudely. Then upstairs like a

Comments (0)