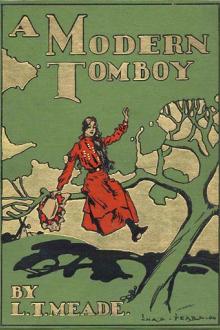

A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Book online «A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

Rosamund now suggested that they should both compete for a small prize. She chose a subject which she herself knew nothing about, therefore she said they were very nearly equal. They both did compete, and perhaps Rosamund did not exactly put forth her full powers; but, anyhow, in the end Irene won, and her delight was beyond bounds. She rushed down to her mother's boudoir and showed her the beautifully bound volume of Kingsley's Water Babies which was the prize she had won.

"I have got it through merit," she said. "Think of my getting anything through merit!"

Lady Jane very nearly cried, but she restrained herself, for Rosamund followed; whose face, with its slightly flushed cheeks and its eyes full of light and happiness, showed Lady Jane what a splendid character her young friend possessed. How could she ever thank God enough for having sent such a girl to her house?

Yes, lessons went on well, and Irene especially made great progress in her musical studies. She had always been fond of music as a little child. In her wildest moods, when Lady Jane had played for her she had become quiet, and crept close to her mother, laid her charming little head against her mother's knee, and listened with wide-open eyes. As she grew a little older she began to practice for herself, inventing her own melodies—nonsense, of course, but still with a certain promise in them.

Now Rosamund suggested that Irene should give up music with Miss Frost, for Miss Frost's style was by no means encouraging, and should take her lessons from the first-rate master who came twice a week from Dartford. It was amazing how quickly Irene made progress under this tuition. In the first place, Mr. Fortescue would not hear of any nonsense. He did not mind Irene's airs or her little attempts to subdue him; he simply desired her to do things, and when she failed he pounded her soundly on her knuckles.

"That is not the way to bring out that note," he would say; and then he would sit down to the piano himself, and ring out great melodies in the most splendid style, until the enthusiastic child almost danced with pleasure.

"Oh, is there any chance of my playing like that?" she once exclaimed.

"Every chance, and a great deal better, if you really take to it with all your heart and soul," was his response.

Rosamund was also intensely fond of music, and the girls were happy over their musical studies; in short, Irene, from having an aimless life, in which she did nothing but torment others, was now leading a full and happy existence. She had her distinct hours for work and distinct hours for play. She had a companion who delighted her; and toads, wasps, spiders, and even leeches lost their charm.

One day, to Rosamund's great delight, Irene suggested that Fuzz and Buzz and all their children should go back to the nearest chemist. This was no sooner thought of than done. Certainly it was a very great step in Irene's reform; but it must not be supposed that such a character could become good all of a sudden. It takes a lifetime, and perhaps more than a lifetime, to make any of us really good, and Irene was not by nature a very amiable child. She had been terribly spoiled, it is true, and but for Rosamund might have been an annoyance and a torment to every one as long as she lived. But she had splendid points in her character, and these were coming slowly to the fore.

Still, there were times when she was exceedingly naughty. Rosamund, having written to her mother, and so set her mind completely at rest, thought no longer of the sort of disgrace in which she was living as regarded the Merrimans. She was now anxious that Irene should make friends.

"There is no use whatever," she said, "in shutting a girl like Irene up with me. She ought to know the Singletons. I will ask Lady Jane if we may drive over some day and see them. Why shouldn't we go to-day? Irene has been quite good this morning. I dare say I could manage it. She won't like meeting Miss Carter; but she must get over that feeling. There's nothing for it but for her to live like ordinary girls. If she refuses, I shall beg of Lady Jane to take us both from The Follies, to take a house somewhere else for at least six months, and to let us make new friends. But that does seem ridiculous, when The Follies is such a lovely place, and Irene's real home. Of course, I can't always stay with her, although I mean to stay for the present."

Rosamund ran up to Lady Jane, who was pacing up and down on the terrace. Irene, as usual, was in her boat. She was floating idly about the lake. The day was intensely hot. She wore a graceful white frock and her pretty white shady hat; her little white hand was dabbling in the water, and her graceful little figure was looking almost like a nymph of the stream.

Lady Jane turned with a beaming face to Rosamund.

"What is it now, my dear?" she said.

"Well, of course, you have heard the good news. Everything is all right at the Merrimans', neither Irene nor I have taken the infection, none of the other girls have taken it, Jane is getting well again, and I have written a full account of everything to mother."

"That doesn't mean, my darling Rosamund, that you are going to leave us? I really couldn't consent to part with you. I can never, never express all that you have been to me," said poor Lady Jane, her eyes filling with tears.

"Well, I can only part from you by going back to mother, for they won't receive me any more at the Merrimans'."

"But why not, Rosamund?"

"Because I have taken up with Irene. But we needn't go into that now. What I want to know is, may Irene and I have the governess-cart, and may Miss Frost go with us, and may we drive over to the Singletons'?"

"Of course you may, Rosamund. But I am afraid it will be you and Miss Frost alone, for nothing would induce Irene to set foot inside that place. She has always refused, notwithstanding every effort of our dear clergyman to invite her to visit them. I have asked the children here, for they are nice children; but they are too much afraid of her to come. I do not think you will find the visit a success, even if you do induce Irene to accompany you."

"But I think I shall," said Rosamund calmly. "You know," she added, "Irene is not what she was."

"Indeed she is not. She is very different. I am beginning at last to enjoy my life and to appreciate her society. How beautiful she is, and how you have brought out her beauty!"

"Her beauty was given her by God," said Rosamund. "But, of course, now that she is learning, and becoming intelligent, and thinking good thoughts instead of bad thoughts, all these things must be reflected on her face. I want her to have other friends besides me, for I cannot always be with her, and I cannot tell you what a splendid girl I think Maud Singleton is."

"But then there is poor Miss Carter. Irene nearly killed her."

"Miss Carter is quite well and happy at the Singletons', and they just adore her, and Irene ought to apologize to her. I mean to make her when I get the chance. Perhaps not to-day. Anyhow, may we go?"

"You certainly may, and I wish you all success."

Rosamund danced away, and ran down the winding path to the edge of the lake.

"Irene, I want you to come in," she said. "I want to speak to you."

Irene rowed lazily back to the shore. She still sat in her boat and looked up at Rosamund.

"Will you get in?" she said. "There is a little breeze on the water; there is none on the land. What are you looking so solemn about?"

"I am not solemn at all. I want us to have fun this afternoon. It is rather dull here, just two girls all by themselves. I don't think that I can stay with you much longer unless you allow me to have other friends."

"Good gracious!" said Irene. "Perhaps I'd better get out. You look so very solemn."

"No, I'm not solemn exactly; but I want to have other friends. Will you get out, and may I talk to you?"

Irene jumped with alacrity out of the boat, and Rosamund helped her to moor it.

"Now, what is it?" said Irene.

"Well, Irene, it is just this: I want to go and see the Singletons this afternoon, and your mother says we may have the governess-cart, and if they ask us to stay to tea we may stay."

"We? What do you mean by 'we'?"

Irene backed away, her face crimson, her eyes dancing with all their old malignancy.

"I mean," said Rosamund, "you and I and Miss Frost."

"You mean that I am to go to the house where Carter is—Carter, whom I nearly killed?"

"I want you to come with me. Won't you, darling?"

"I wish you wouldn't speak in that coaxing voice. People don't speak in such a tender way to me. But no, I can't go. I really can't. I'd be afraid. I can't meet Carter."

"But if you come with me you needn't say much. We'll go together, and you'll find it quite pleasant. I do want to talk to other girls, for you know I've given up all my friends for you, or practically given them up for your sake."

"I wish you wouldn't throw in my face all that you have done for my sake. You had better go, and let me get back to my wild ways. I had great fun with my toads and frogs and spiders and leeches, and having everybody looking at me with scared faces. On the whole, I had much more fun than I have now. I was thinking about that as I was floating in the boat, and the thought of Frost came over me, and I wondered what she would do if I took her into a current in the middle of the lake and frightened her as I frightened Carter. Perhaps even the thought of her little brother and sister wouldn't keep her here any longer. Well, I was thinking those thoughts; but then I thought of you, and somehow or other I felt it worth while to be good just for the sake of your presence; and in many ways you have made my life more interesting. But if you want me to be friends with those Leaves; if you want me to see that dreadful, that terrible Carter again; and then if you want me to go to the Merrimans', and shake hands with that Lucy, and be agreeable to all those people, I really can't."

"Very well, Irene, you can please yourself."

Rosamund turned on her heel and walked away. Irene stood and watched her. She stood perfectly still for a minute, her face changing color, her lips working, her eyes flashing. Then she took up a great sod of wet grass and flung it after Rosamund, making a deep stain on her pretty muslin dress. Rosamund did not take the slightest notice. She walked calmly back to the house, went up to her own room, and sat there quite still. Irene got back into the boat.

"I do wish Frost was somewhere near," she thought to herself. "I won't go and see those Leaves; nothing will

Comments (0)