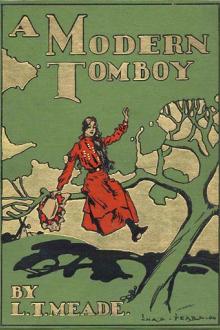

A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Book online «A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

Lucy looked with great approbation at Miss Archer when she took her seat opposite the tea-tray.

"She will bring order into this chaos," thought the girl. "She will force all these girls to behave properly. She will insist on order. I see it in her face."

But as the thought passed through Lucy's mind, Rosamund jumped suddenly up from her own place, requested Phyllis Flower to change with her, and sat down close to Miss Archer. During tea she talked to the English governess in a low tone, asking her a great many questions, and evidently impressing her very much in her favor.

"Oh, dear!" thought Lucy, "if this sort of thing goes on I shall lose my senses. If there is to be any order, if the whole scheme which mother has thought out so carefully, and father has approved of, means to establish a girl like Rosamund Cunliffe here as our leader, so that we are forced to do every single thing she wishes, I shall beg and implore of father and mother to let me go and live with Aunt Susan in the old Rectory at Dartford."

Lucy's cheeks were flushed, and she could scarcely keep the tears back from her eyes. After tea, however, as she was walking about in front of the house, wondering if she should ever know a happy moment again, Miss Archer made her appearance. When she saw Lucy she called her at once to her side.

"What a nice girl Rosamund Cunliffe seems!" was her first remark.

"Oh! don't begin by praising her," said Lucy. "I don't think I can quite stand it."

"What is the matter, my dear? You are little Lucy Merriman, are you not—the daughter of Mrs. Merriman and the Professor?"

"I am."

"And this house has always been your home?"

"I was born here," said Lucy almost tearfully.

"Then, of course, you feel rather strange at first with all these girls scattered about the place. But when lessons really begin, and you get into working order, you will be different. You will have to take your place with the others in class, and everything is to be conducted as though it were a real school."

"I will do anything you wish," said Lucy, and she turned a white face, almost of despair, towards Miss Archer. "I will do anything in all the world you wish if you will promise me one thing."

Miss Archer felt inclined to say, "What possible reason have you to expect that I should promise you anything?" but she knew human nature, and guessed that Lucy was troubled.

"Tell me what you wish," she said.

"I want you not to make a favorite of Rosamund Cunliffe. Already she has begun to upset everything—last night all the drawing-room arrangements, her own bedroom afterwards; then, to-day, the other girls have done nothing but obey her. If this goes on, how is order to be maintained?"

Miss Archer looked thoughtful.

"From the little I have seen of Rosamund, she seems to be a very amiable and clever girl," she said. "She evidently has a great deal of strength of character, and cannot help coming to the front. We must be patient with her, Lucy."

Lucy felt a greater ache than ever at her heart. She was certain that Miss Archer was already captivated by Rosamund's charms. What was she to do? To whom was she to appeal? It would be quite useless to speak to her mother, for her mother had already fallen in love with Rosamund; and indeed she had with all the young girls who had arrived such a short time ago. Mrs. Merriman was one of the most affectionate people on earth. She had the power of taking an unlimited number of girls, and boys, too, into her capacious heart. She could be spent for them, and live for them, and never once give a thought to herself. Now, in addition to the pleasure of having so many young people in the house, she knew she was helping her husband and relieving his mind from weighty cares. The Professor could, therefore, go on with the writing of his great work on Greek anthology; even if the money for this unique treatise came in slowly, there would be enough to keep the little family from the products of the school. Yes, he should be uninterrupted, and should proceed at his leisure, and give up the articles which were simply wearing him into an early grave.

Lucy knew, therefore, that no sympathy could be expected from her mother. It is true that her father might possibly understand; but then, dared she worry him? He had been looking very pale of late. His health was seriously undermined, and the doctors had spoken gravely of his case. He must be relieved. He must have less tension, otherwise the results would be attended with danger. And Lucy loved him, as she also loved her mother, with all her heart and soul.

When Miss Archer left her, having nothing particular to do herself and being most anxious to avoid the strange girls, she went up the avenue, and passing through a wicket-gate near the entrance, walked along by the side of a narrow stream where all sorts of wild flowers were always growing. Here might be seen the blue forget-me-not, the meadow-sweet, great branches of wild honeysuckle, dog-roses, and many other flowers too numerous to mention. As a rule, Lucy loved flowers, as most country girls do; but she had neither eyes nor ears for them to-day. She was thinking of her companions, and how she was to tolerate them. And as she walked she saw in a bend in the road, coming to meet her, a stout, elderly, very plainly dressed woman.

Lucy stood still for an instant, and then uttered a perfect shout of welcome, and ran into the arms of her aunt Susan.

Mrs. Susan Brett was the wife of a hard-working clergyman in a town about ten miles away. She had no children of her own, and devoted her whole time to helping her husband in his huge parish. She spent little or no money on dress, and was certainly a very plain woman. She had a large, pale face, somewhat flat, with wide nostrils, a long upper lip, small pale-blue eyes, and a somewhat bulgy forehead. Plain she undoubtedly was, but no one who knew her well ever gave her looks a thought, so genial was her smile, so hearty her hand-clasp, so sympathetic her words. She was beloved by her husband's parishioners, and in especial she was loved by Lucy Merriman, who had a sort of fascination in watching her and in wondering at her.

From time to time Lucy had visited the Bretts in their small Rectory in the town of Dartford. Nobody in all the world could be more welcome to the child in her present mood than her aunt Susan, and she ran forward with outstretched arms.

"Oh, Aunt Susy, I am glad to see you! But what has brought you to-day?"

"Why, this, my dear," said Mrs. Brett. "I just had three hours to spare while William was busy over his sermon for next Sunday. He is writing a new sermon—he hasn't done that for quite six months—and he said he wanted the house to himself, and no excuse for any one to come in. And he just asked me if I'd like to have a peep into the country; that always means a visit to Sunnyside. So I said I'd look up the trains, and of course there was one just convenient, so I clapped on my hat—you don't mind it being my oldest one—and here I am."

"Oh, I am so glad!" said Lucy. "I think I wanted you, Aunt Susan, more than any one else in all the world."

She tucked her hand through her aunt's arm as she spoke, and they turned and walked slowly along by the riverside.

Mrs. Brett, if she had a plain face, had by no means a correspondingly plain soul. On the contrary, it was attuned to the best, the richest, the highest in God's world. She could see the loveliness of trees, of river, of flowers. She could listen to the song of the wild birds, and thank her Maker that she was born into so good a world. Nothing rested her, as she expressed it, like a visit into the country. Nothing made the dreadful things she had often to encounter in town seem more endurable than the sweet-peas, the roses, the green trees, the green grass, the fragrance and perfume of the country; and when she saw her little niece—for she was very fond of Lucy—looking discontented and unhappy, Mrs. Brett at once perceived a reason for her unexpected visit to Sunnyside.

"We needn't go too fast, need we?" she said. "If we go down this path, and note the flowers—aren't the flowers lovely, Lucy?"——

"Yes," replied Lucy.

"We shall be in time for tea, shall we not? But tell me, how is your father, dear? I see you are in trouble of some sort. Is he worse?"

"No, Aunt Susy; I think he is better. He has had better nights of late, and mother is not so anxious about him."

"Then what is the worry, my love, for worry of some sort there doubtless is?"

"It is the girls, Aunt Susy."

"What girls, my love?"

"Those girls that mother has invited to finish their education at Sunnyside. They came yesterday, and the teachers, Mademoiselle Omont and Miss Archer, arrived to-day. And the girls don't suit me—I suppose I am so accustomed to being an only child. I cannot tell you exactly why, but I haven't been a bit myself since they came."

"A little bit jealous, perhaps," said Aunt Susan, giving a quick glance at Lucy's pouting face, then turning away with a sigh.

"You will be surprised, Lucy," she continued after a pause, "when I tell you that I used to be fearfully jealous when I was young. It was my besetting sin."

"Oh, Aunt Susy, I simply don't believe it!"

"You don't? Then I will show you some day, when you and I are having a snug evening at the old Rectory at Dartford, a letter I once received from my dear father. He took great pains to point out to me my special fault, as he called it; and his words had a wonderful effect, and I went straight to the only source of deliverance, and by slow degrees I lost that terrible feeling which took all the sunshine out of my life."

"Tell me more, please, Aunt Susan," said Lucy.

"Well, you see, dear, I was not like yourself an only child. I was one of several, and I was quite the plain one of the family. I am very plain now, as you perceive; but I had two beautiful little sisters. They were younger than I, and Florence had quite a beautiful little face, and so had Janet. Wherever they went they were admired and talked about, and I was thought nothing of. Then I had three brothers, and they were good-looking, too, and strong, and had excellent abilities, and people thought a great deal about them; but no one thought anything about me. I was the eldest, but I was never counted one way or the other as of the slightest consequence. My people were quite rich, and Florence and Janet were beautifully dressed, and taken down to the drawing-room to see visitors; but I was never noticed at all. I could go if I liked, but it did not gratify anybody, so by degrees I stayed away. You do not know what bitter feelings I had in my

Comments (0)