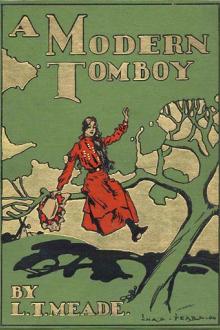

A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Book online «A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

"Irene," she said, "you ought to have a proper introduction to Agnes. This is Agnes Frost."

Little Agnes came shyly forward and looked straight up with her big dark eyes at Irene. She was a smaller girl, and if possible still more delicate-looking, but very pretty and interesting. Hugh, who had been having such an interesting debate with Irene, now stepped up to Agnes and flung his arm round her neck.

"She is tired, poor baby!" he said. "She wants to go in and go to sleep for an hour. You have a headache, haven't you, little un?"

"Yes," replied Agnes. "My head aches rather badly. It is the train—it always makes me feel sick."

"Then shall I take you into the house?" said Irene.

She forgot Hugh, to Hugh's own amazement. She took Agnes' tiny hand and led her toward the house. Miss Frost longed to follow; but Rosamund held her back.

"No, no. On no account go with them," she said. "Let Irene feel that she has got possession of the little one at once. You see how confidently Agnes gave her hand. That is the best possible sign. Let her take her to her room and see after her comforts."

Irene—who never before in all her life had any creature to look up to her, who was looked down upon with terror and shunned by her fellow-creatures, with the exception of Rosamund, who ruled her, although with the weapons of love—felt an altogether new sensation now as the little creature, not so old as herself, clung to her confidently.

"I shall be glad to lie down," said little Agnes. "Have you ever gone long journeys by train, and does your head ache?"

"No, I haven't gone long journeys by train; but I will take you to your room and draw down the blinds, and you can go to sleep."

"May I? That is what I want more than anything else. If I could sleep for half-an-hour I should feel better."

"You shall, of course," said Irene.

She walked slowly through the house, holding this small, dependent creature by the hand. Was she not her guest? She forgot all about poor Miss Frost, whose heart was devoured with jealousy; for little Agnes, in the olden times, had clung to her. Now she clung close to Irene.

"You are so nice," she said, "and so pretty! I am glad I am coming to spend the holidays with you."

"Are you?" said Irene, with a queer look.

James the footman saw them as they went upstairs; and Lady Jane stood at the drawing-room door, but made no sign.

Irene presently reached the small but very prettily arranged room which the little girl was to occupy.

"This room opens out of Frosty's," she said.

"Who is Frosty?" asked the child.

"My governess, of course, and your sister."

"Oh! but I'd rather sleep in a room opening out of yours. Can't I? Of course, I'm very fond of my dear sister Emily; but you are so fresh, and I think you will take care of me."

"There is a tiny room which you could have next to mine, and we could have the doors open, and I promise to be awfully careful of you, if you really like it best," said Irene, who felt more and more charmed at the dependence of this small creature.

"Yes, I know I'd like it best. But may I lie down here just for the present?"

"Of course you may."

Irene herself helped to remove Agnes's boots. She laid her on the bed and put the coverlet over her, and then rang the bell. One of the housemaids appeared.

"I want some tea," said Irene in a lofty tone, "for little Miss Agnes Frost. You can bring it up on a tray with cakes, and I can have some at the same time. And please arrange the pink bedroom opening out of mine for Miss Agnes to sleep in to-night. Do you hear? Do you understand?"

"Yes, miss, of course," said the girl, retiring in a great hurry in the utmost amazement; for over Irene's curious, expressive little face had come a new look—a look of protection, almost of motherhood.

She bent down and kissed little Agnes; and Agnes put her thin arms round her neck, and said, "Oh, you are so beautiful, and so—so kind to me! Of course, I love dear sister Emily; but she is old, and you are young. I want somebody young—somebody like you—to be kind to me, for I am such a timid little girl. Will you take care of me?"

"I vow I will," said Irene.

"Then you will hold my hand if I do drop asleep—for this is such a big, strange house, and I may feel frightened?"

"No one shall frighten you while I am here," was Irene's answer.

The housemaid, the veritable Susan who had once spoken such harsh things to Irene, presently came in with the tea-tray. Irene herself poured out the tea and brought it to little Agnes, who drank it feverishly, and then lay down; but she was too tired and too ill from her journey to care to eat any cakes. Just as she was dropping off to sleep, Miss Frost put in an anxious face.

"Run away, Frosty; run away at once. She is my charge," said Irene; and Miss Frost, smothering the jealousy which could not but arise in her heart, left the room.

This was a position she had not expected. Nevertheless, there was no help for it.

"Now, I am going to munch cakes, and you shall sleep. Would you like me to tell you a story while you are dropping off to sleep?"

"If it isn't at all frightening—if it is nice."

"I will tell you about the little princess in Hans Andersen. My darling, my noble, my beloved Rosamund told it to me, and I will tell it to you. Now then, listen."

Irene began. She could tell that marvelous tale with all the grace and unction and passion which her genius inspired her with. Little Agnes listened and listened, and forgot her terrors. She clung closer and closer to her companion, and when the story came to an end her starry eyes were brimful of tears.

"Oh, that is very sweet!" said the little girl. "And now the little princess is one of the spirits of the air, and she has won something"——

"She has won her soul," said Irene in a strange, strangled sort of voice; for it occurred to her that, after all, the little princess might have a greater resemblance to herself than ever she had thought. For was she not fighting for her own soul all this time?

While little Agnes slept, Irene sat in the room by her side still and quiet. There were voices heard in the distance; the manly voice of Hughie, who was somewhat dictatorial, and was ordering people about, and telling this person or the other that they were doing things wrong, and was terrifying his sister by his manly ways. There was Rosamund's voice, who was quite delighted at the turn events had taken. There was Miss Frost's voice, anxious about Agnes, and quite sure that Irene must end by terrifying her. There was Rosamund again persuading and soothing, and doing all she could to allow the present order of things to take a natural course. But upstairs in the pretty little bedroom the child slept peacefully; and Irene looked at her and felt new sensations, new hopes, new desires struggling in her breast. She had loved Rosamund because she was so strong. She was beginning to love little Agnes because she was so weak. What a strange tangle the world was! What was happening to her? And why was that curious living thing within so satisfied, so happy, so sure of itself?

It was between six and seven o'clock when Agnes, neatly and tidily dressed, came downstairs, accompanied by Irene, who led her straight into the drawing room.

"This is Agnes Frost, mothery," said Irene; "and you are on no account to tire her. She is better now. Are you not, Agnes?"

"Yes, I am better," replied the little girl. "But who is this grand lady you are introducing me to?"

"This is my mother—Lady Jane."

"I never knew anybody called 'Lady' before."

"Well, my mother is Lady Jane—Lady Jane Ashleigh."

Little Agnes held out a timid hand.

"How do you do, dear? I hope you have got over the fatigue of your journey."

"Oh, yes, mothery, she is quite well now. Don't worry her," said Irene almost rudely. "I am going to take her out in the boat on the lake."

"Be sure you are very careful."

"I will be careful enough."

Just then Miss Frost came in.

"Agnes, I hear Irene wants to take you out in the boat. You are not to go."

"But she has promised," said little Agnes.

She raised confiding dark eyes to her new friend's face.

"You must trust me, Frosty. Don't be a perfect goose," said Irene; and taking Agnes' hand, they went down across the summer lawn to the place where the boat was moored. By-and-by Irene was seen by those who watched, gently rowing among the water-lilies, with little Agnes at the other end of the boat.

"What a beautiful girl you are!" little Agnes kept saying; "and how happy my sister ought to be, living always with you!"

"Don't ask her if she is happy for a day or two. I have given directions about your room. You shall sleep in the little pink room next to mine."

CHAPTER XIX. A SORT OF ANGEL.Irene pulled with swift, sure strokes across the summer lake. The lake was one of the great features of the place. It was a quarter of a mile wide, and half a mile in length, and had been carefully attended to by owner after owner for generations; so that groups of water-lilies grew here, and swans arched their proud white necks and spread out their feathered plumes. Little Agnes had never seen anything so lovely before, and when she bent forward and saw her own reflection in the water she gave a scream of childish pleasure.

"Oh, how happy sister Emily must be!" was her remark.

Again Irene made the strange answer, "Don't ask for a day or two."

Then little Agnes raised grave dark eyes to Irene's face.

"But any one would be happy with you," she said. "To look at you is such a comfort."

"Tell me about yourself," said Irene suddenly, shipping her oars, bending forward, and fixing her intensely bright eyes on the child.

She did not feel at all like a changeling now. That wild thing in her breast was still. She felt somewhat like a mother, somewhat like an ordinary little girl might feel towards a loved baby-sister, or even towards a doll. This new sense of protection had a marvelous effect upon her. She would not have minded if little Agnes had crept into her arms and laid her head on her breast.

"Tell me what you did before you came here," she said.

"But don't you know?" said Agnes. "Sister Emily has been living with you for a long time. She must have told you about me."

"I am ashamed to say I never asked her anything about you."

"I suppose that is because you are very thoughtful. You were determined—yes, determined—not to give her pain. She is always so sad when she thinks of us; but Hughie and I are not really unhappy. We don't mind things now."

"What do you mean by 'now'? Tell me—do tell me."

"Oh, we are at school. Hughie is at a pretty good school, although it is rather rough. He is learning hard. He is to be apprenticed to a trade some day. Dear sister Emily cannot afford to bring him up as a gentleman; but she is saving every penny of her money to put him into a really good trade. Perhaps he will be a bookbinder, or perhaps a cabinetmaker."

"But people of that sort are not gentry," said Irene. Then she colored and bit her lips.

Little Agnes had seen so much of the rough side of life that she was not

Comments (0)