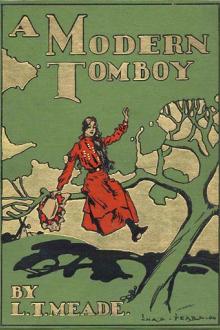

A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Book online «A Modern Tomboy, L. T. Meade [books you have to read .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

Irene took her hand affectionately, guessing little of her thoughts.

"Do come and show us round, Rosamund," she said. "I know Aggie is tired. Aren't you, darling?"

"Oh, no," said Agnes. "I'd like to go out presently and have a walk all alone with you, Irene."

"Then of course you shall, dear."

"But there's no time to-night," said Rosamund. "We have barely time to get our things unpacked and get ready for supper. You know this is school, and I told you what school meant."

"You did," said Irene, raising her bright, wild eyes to her companion's face; "but I confess I had forgotten it. This house seems like any other house, only not so handsome. It isn't nearly as big as The Follies, and the people don't seem so rich; and I have seen fat Mrs. Merriman all my life driving about with the cob and the governess-cart; and I have seen Professor Merriman, too, with his bent back and long hair. But I never chanced to come across Lucy except that time in church, and then I thought her horrible. Why should I alter my plans because of the Merrimans? I don't intend to do it."

"You must, Irene. You promised me that you would try to be good. Come, look at Agnes."

Agnes was gazing up at her chosen companion, at the girl she loved best in the world, with wonder in her dark eyes. It was not a reproving look those eyes wore; it was a sweet, astonished, and yet slightly pained gaze. It conquered Irene on the spot. She bent down and kissed the little one.

"You never thought I should be naughty, did you?" said Irene, lowering her voice.

"You couldn't! you couldn't! You are the best girl in all the world," whispered Agnes.

"Then I will make a tremendous effort to be good for your sake."

These words were also said in a whisper, and by this time the girls had reached their own room, which they were to share together. A door opened into Rosamund's room, and thus the three who were to be so closely united during the greater part of their lives were more or less in the same apartment.

"It does seem strange not to have dear Jane Denton here," said Rosamund; "but she seems to be still so delicate that she won't come back to school this term. Now, shall I help you to unpack, Irene? And shall I help you to put on a pretty frock for supper? I want you to look as nice as possible. All the girls are just dying to see you."

At that moment there came a knock at Rosamund's door. Rosamund flew to open it. Laura Everett stood without.

"So you have come back, Rosamund! How glad I am to see you! May I come in?"

"If you don't mind, not for a few minutes," said Rosamund. "May I have a chat with you after supper, or one day after lessons?"

"Of course to-night. We can walk about in the corridors if it is too cold to go out-of-doors. But is it absolutely true—I only heard it as a whisper—that you have brought Irene Ashleigh, the terror of the neighborhood, here?"

"She will be a terror no longer if you will all be kind to her," said Rosamund. "I have a great deal to say to you; but don't keep me now. She has come, and so has dear little Agnes Frost, and—oh! do ask the other girls to be kind, and not to take any special notice. You will, won't you?"

"I'm sure I'd do anything for you," said Laura. "I think you were splendid all through. I cannot tell you how I have admired you, and how I spoke to mother about you in the holidays; and mother said that though you had not done exactly right, yet you were the finest girl she had ever heard of or come across, and she was very glad to think that you and I might be in a sort of way friends."

"Well, let us be real friends," said Rosamund affectionately. "Now, don't keep me any longer. I have as much as I can do to get my couple ready to make a respectable appearance at supper."

Laura ran off to inform her school-fellows that the noted, the terrible Irene was in very truth a pupil at Mrs. Merriman's school. The girls, of course, had heard that Irene was coming, and that Rosamund had been forgiven, and, notwithstanding her disobedience, was returning to the school. But although they believed the latter part of this intelligence, they doubted the former, thinking it quite impossible that any sane people would admit such a character as Irene into their midst. But when Laura came downstairs and told her news, the girls looked up with more or less interest in their faces.

Annie Millar, who was Laura's special friend, said that she was glad.

"She needn't suppose that I'll be afraid of her," said Annie.

"And she needn't think that I'll be afraid of her," said Phyllis Flower. "She may try her toads and her wasps if she likes on me; but she won't find they have much effect."

"Oh, do stop talking!" said Laura. "Can't you understand that if Irene is to be a good girl we must not bring things of that sort up to her? I believe she will be good, and I think Rosamund is just splendid. Yes, Lucy, what did you say?"

Now, Lucy had up to the present been one of Laura's great friends. Their mothers had been friends in the old days, and the clever, bright, intelligent Laura suited Lucy to perfection. But Lucy had imbibed all the traditions with regard to the willful Irene, and was horrified at the thought of having her now in the school. She was also angry at Rosamund's being reinstated; in short, she was by no means in a good temper. She thought herself badly treated that the news of the advent of these two young people had been kept from her, and was not specially mollified when her mother came into the room and told her that her father wished to speak to her for a minute or two in his study.

The girl ran off without a moment's delay, and entering the study, went straight up to the Professor, who, gentle, patient as of old, laid his hand on her shoulder.

"Well, Lucy," he said, "and so school begins, and the old things resume their sway."

"I don't think they do," retorted Lucy. "It seems to me that they are giving place to new. Why is it, father, that a girl whom you expelled has come back again to our dear little select, very private school? And why has she brought the very naughtiest girl in the whole neighborhood to be her companion?"

"I can only tell you this in reply, Lucy: Rosamund, although she was naughty, was also noble."

"That is impossible," said Lucy, with a toss of her head.

"It is difficult for you to understand; but it is the case. She was actuated by a brave motive, and has done a splendid work. I confess I was very angry with her at the time; but dear Mr. Singleton—such a Christ-like man as he is—opened my eyes, and told me what a marvelous effect Rosamund was having on little Irene Ashleigh, whom every one was afraid of, and who was in consequence being absolutely ruined. It was at Singleton's request that I reinstated Rosamund in the school, and it was further at his request and that of Lady Jane Ashleigh that I decided not to part the two girls, but to allow them to come here for at least a term. So Rosamund and Irene are both members of the school, and I desire you, Lucy, as my daughter, not to repeat to any of your fellow-pupils the stories you may have heard in the past with regard to Irene. I desire you to be kind to her, and if you cannot be friends with her, at least to leave her alone. You have your own friends, Laura Everett"——

"Oh, Laura has already gone over to the enemy," said Lucy. "Why, she was talking and preaching as hard as ever she could just now, when mother came in and said that you wanted me."

"Well, my dear, I did want to speak to you. I wanted to say just what I have said. You will attend to my instructions. You understand?"

"I understand, father," said Lucy; and she left the study with her fair head slightly bent.

There was a puzzled expression on her face. What was the meaning of it all? Never in her life, which would soon extend to sixteen years, had Lucy Merriman consciously done a wrong action. She had always been obedient to her parents; she had always been careful and prim, and, as she considered, thoughtful for others. She adored her father and mother. She herself had been willing to sacrifice her position as a happy only girl to become a member of the school, just to help her father out of his difficulties, and to enable his health to be restored, and now she was reprimanded because she could not see that wrong was right. What was the matter with Rosamund? Who could consider her conduct in any other but the one way? And yet here was Mr. Singleton inducing her father to overlook her fault.

"I felt dissatisfied when father expelled her," thought the girl. "But now he has taken her back again; and that awful ogre, that terror, has come here. What does it all mean? It's enough to turn a good girl naughty; that's all I've got to say."

There was a pretty sort of winter parlor where the girls always waited until the meals were served. Lucy re-entered it now, and found most of her companions waiting for her. She was scarcely there a moment before the gong sounded, and at the same instant Rosamund, followed by Irene, who was holding little Agnes's hand, entered the room.

Now, report had said a great deal in disfavor of Irene Ashleigh. She was the queer girl who wore the unkempt red dress, who did the strangest, wildest, maddest things, who terrified her governesses, who was cruel to the servants, who made her mother's life one long misery. But report had never mentioned that there was a charm in her wild face, in those speaking eyes; and that the same little figure clothed in the simplest, prettiest white could look almost angelic. No, angelic was hardly the word. Perhaps charming suited her better. Beyond doubt she was beautiful, with a willowy, wild grace which could not but arrest attention, and all the other girls immediately owned to a sense of inferiority in her presence. But Irene was so endowed with nature's grace that she could not do an awkward thing; and then the child who accompanied her, the small unimportant child, was as beautiful in her way as Irene was in hers. So charming a pair did they make, those two, each of them dressed in the purest white, that Rosamund, who was considered quite the handsomest girl in the school, seemed to sink into commonplace in comparison. But no one had time to make any remark.

Irene said lightly, "Oh, so you are the others!" and then nodded to one and all; and turning to Agnes, she said in a low tone, "These are the rest of the girls, Aggie; and I'm ever so hungry. Aren't you, Aggie?"

Mrs. Merriman came in and conducted her young group to the room where supper was laid out, and here the first cross occurred to disturb Irene's good temper; for Agnes was placed at the other side of

Comments (0)