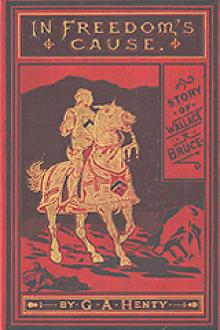

In Freedom's Cause, G. A. Henty [always you kirsty moseley .TXT] 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

- Performer: -

Book online «In Freedom's Cause, G. A. Henty [always you kirsty moseley .TXT] 📗». Author G. A. Henty

Archie eagerly drank in the tale of Wallace’s exploits, and his soul was fired by the desire to follow so valiant a leader. He was now sixteen, his frame was set and vigorous, and exercise and constant practice with arms had hardened his muscles. He became restless with his life of inactivity; and his mother, seeing that her quiet and secluded existence was no longer suitable for him, resolved to send him to her sister’s husband, Sir Robert Gordon, who dwelt near Lanark. Upon the night before he started she had a long talk with him.

“I have long observed, my boy,” she said, “the eagerness with which you constantly practise at arms; and Sandy tells me that he can no longer defend himself against you. Sandy, indeed is not a young man, but he is still hale and stout, and has lost but little of his strength. Therefore it seems that, though but a boy, you may be considered to have a man’s strength, for your father regarded Sandy as one of the stoutest and most skilful of his men-at-arms.

I know what is in your thoughts; that you long to follow in your father’s footsteps, and to win back the possessions of which you have been despoiled by the Kerrs. But beware, my boy; you are yet but young; you have no friends or protectors, save Sir Robert Gordon, who is a peaceable man, and goes with the times; while the Kerrs are a powerful family, able to put a strong body in the field, and having many powerful friends and connections throughout the country. It is our obscurity which has so far saved you, for Sir John Kerr would crush you without mercy did he dream that you could ever become formidable; and he is surrounded by ruthless retainers, who would at a word from him take your life; therefore think not for years to come to match yourself against the Kerrs.

You must gain a name and a following and powerful friends before you move a step in that direction; but I firmly believe that the time will come when you will become lord of Glencairn and the hills around it. Next, my boy, I see that your thoughts are ever running upon the state of servitude to which Scotland is reduced, and have marked how eagerly you listen to the deeds of that gallant young champion, Sir William Wallace. When the time comes I would hold you back from no enterprise in the cause of our country; but at present this is hopeless. Valiant as may be the deeds which Wallace and his band perform, they are as vain as the strokes of reeds upon armour against the power of England.”

“But, mother, his following may swell to an army.”

“Even so, Archie; but even as an army it would be but as chaff before the wind against an English array. What can a crowd of peasants, however valiant, do against the trained and disciplined battle of England. You saw how at Dunbar the Earl of Surrey scattered them like sheep, and then many of the Scotch nobles were present. So far there is no sign of any of the Scottish nobles giving aid or countenance to Wallace, and even should he gather an army, fear for the loss of their estates, a jealousy of this young leader, and the Norman blood in their veins, will bind them to England, and the Scotch would have to face not only the army of the invader, but the feudal forces of our own nobles. I say not that enterprises like those of Wallace do not aid the cause, for they do so greatly by exciting the spirit and enthusiasm of the people at large, as they have done in your case. They show them that the English are not invincible, and that even when in greatly superior numbers they may be defeated by Scotchmen who love their country. They keep alive the spirit of resistance and of hope, and prepare the time when the country shall make a general effort. Until that time comes, my son, resistance against the English power is vain. Even were it not so, you are too young to take part in such strife, but when you attain the age of manhood, if you should still wish to join the bands of Wallace — that is, if he be still able to make head against the English — I will not say nay. Here, my son, is your father’s sword. Sandy picked it up as he lay slain on the hearthstone, and hid it away; but now I can trust it with you. May it be drawn some day in the cause of Scotland! And now, my boy, the hour is late, and you had best to bed, for it were well that you made an early start for Lanark.”

The next morning Archie started soon after daybreak. On his back he carried a wallet, in which was a new suit of clothes suitable for one of the rank of a gentleman, which his mother had with great stint and difficulty procured for him. He strode briskly along, proud of the possession of a sword for the first time. It was in itself a badge of manhood, for at that time all men went armed.

As he neared the gates of Lanark he saw a party issue out and ride towards him, and recognized in their leader Sir John Kerr. Pulling his cap down over his eyes, he strode forward, keeping by the side of the road that the horsemen might pass freely, but paying no heed to them otherwise.

“Hallo, sirrah!” Sir John exclaimed, reining in his horse, “who are you who pass a knight and a gentleman on the highway without vailing his bonnet in respect?”

“I am a gentleman and the son of a knight,” Archie said, looking fearlessly up into the face of his questioner. “I am Archie Forbes, and I vail my bonnet to no man living save those whom I respect and honour.”

So saying, without another word he strode forward to the town. Sir John looked darkly after him.

“Red Roy,” he said sternly, turning to one who rode behind him, “you have failed in your trust. I told you to watch the boy, and from time to time you brought me news that he was growing up but a village churl. He is no churl, and unless I mistake me, he will some day be dangerous. Let me know when he next returns to the village; we must then take speedy steps for preventing him from becoming troublesome.”

Archie’s coming had been expected by Sir Robert Gordon, and he was warmly welcomed. He had once or twice a year paid short visits to the house, but his mother could not bring herself to part with him for more than a few days at a time; and so long as he needed only such rudiments of learning as were deemed useful at the time, she herself was fully able to teach them; but now that the time had come when it was needful that he should be perfected in the exercises of arms, she felt it necessary to relinquish him.

Sir Robert Gordon had no children of his own, and regarded his nephew as his heir, and had readily undertaken to provide him with the best instruction which could be obtained in Lanark. There was resident in the town a man who had served for many years in the army of the King of France, and had been master of arms in his regiment. His skill with his sword was considered marvellous by his countrymen at Lanark, for the scientific use of weapons was as yet but little known in Scotland, and he had also in several trials of skill easily worsted the best swordsmen in the English garrison.

Sir Robert Gordon at once engaged this man as instructor to Archie.

As his residence was three miles from the town, and the lad urged that two or three hours a day of practice would by no means satisfy him, a room was provided, and his instructor took up his abode in the castle. Here, from early morning until night, Archie practised, with only such intervals for rest as were demanded by his master himself. The latter, pleased with so eager a pupil, astonished at first at the skill and strength which he already possessed, and seeing in him one who would do more than justice to all pains that he could bestow upon him, grudged no labour in bringing him forward and in teaching him all he knew.

“He is already an excellent swordsman,” he said at the end of the first week’s work to Sir Robert Gordon; “he is well nigh as strong as a man, with all the quickness and activity of a boy. In straightforward fighting he needs but little teaching. Of the finer strokes he as yet knows nothing; but such a pupil will learn as much in a week as the ordinary slow blooded learner will acquire in a year. In three months I warrant I will teach him all I know, and will engage that he shall be a match for any Englishman north of the Tweed, save in the matter of downright strength; that he will get in time, for he promises to grow out into a tall and stalwart man, and it will need a goodly champion to hold his own against him when he comes to his full growth.”

In the intervals of pike and sword play Sir Robert Gordon himself instructed him in equitation; but the lad did not take to this so kindly as he did to his other exercises, saying that he hoped he should always have to fight on foot. Still, as his uncle pointed out that assuredly this would not be the case, since in battle knights and squires always fought on horseback, he strove hard to acquire a firm and steady seat. Of an evening Archie sat with his uncle and aunt, the latter reading, the former relating stories of Scotch history and of the goings and genealogies of great families.

Sometimes there were friends staying in the castle; for Sir Robert Gordon, although by no means a wealthy knight, was greatly liked, and, being of an hospitable nature, was glad to have guests in the house.

Their nearest neighbour was Mistress Marion Bradfute of Lamington, near Ellerslie. She was a young lady of great beauty. Her father had been for some time dead, and she had but lately lost her mother, who had been a great friend of Lady Gordon. With her lived as companion and guardian an aunt, the sister of her mother.

Mistress Bradfute, besides her estate of Lamington, possessed a house in Lanark; and she was frequently at Sir Robert’s castle, he having been named one of her guardians under her father’s will.

Often in the evening the conversation turned upon the situation of Scotland, the cruelty and oppression of the English, and the chances of Scotland some day ridding herself of the domination.

Sir Robert ever spoke guardedly, for he was one who loved not strife, and the enthusiasm of Archie caused him much anxiety; he often, therefore, pointed out to him the madness of efforts of isolated parties like those of Wallace, which, he maintained, advanced in no way the freedom of the country, while they enraged the English and caused them to redouble the harshness and oppression of their rule. Wallace’s name was frequently mentioned, and Archie always spoke with enthusiasm of his hero; and he could see that, although Mistress Bradfute said but little, she fully shared his views. It was but natural that Wallace’s name should come so often forward, for his deeds, his hairbreadth escapes, his marvellous

Comments (0)