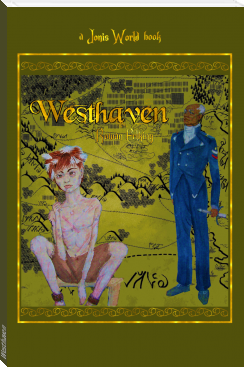

Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Rowan Erlking

Book online «Westhaven, Rowan Erlking [large ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Rowan Erlking

It took days. Through fields of grain and rows of crops and pastures with cows, horses, goats, and sheep, the boy eventually sighted the hills with the town on top of the closest peak. He also saw the rail lines going straight into it.

The general’s boy halted on the edge the farmland where the hedgerows kept properties apart, and he stared at the troops of Sky Children soldiers. They marched on the cobblestone roads near the town. Their automobiles drove over the pavement of the newly built highway. Their trains unloaded their wealthy and traveling poor into the town. They were everywhere.

He looked down at his bare sunburned chest then at his ratty pants and then at the mark on his shoulder making clear whose property he was. Never in his life did he regret more not having a shirt or a hat. He ducked into a nearby hayfield when he saw Sky Children walking down the farm lanes. Already he contemplated where he ought to go next.

“Hey! What ‘choo doin’?” A boy about a year younger than he was strolled through the fields with a hayfork on his shoulder.

Popping up onto his feet, the general’s boy covered his marked shoulder and pulled back. “Nothing.”

Walking closer, the farm boy peered at his face and then closed one eye. “Hey. I’ve seen you before.”

“No, you haven’t.” The general’s boy stepped back further.

The farm boy tossed back his head and laughed. “Yeah, I have! You’re that missing slave those blue-eyes are looking for.”

The general’s boy jumped back then ran around the hay pile, but the farm boy ran after him, his hayfork up.

“Hey! Stop!” The farm boy shouted. “Stop or I’ll stick you!”

But the general’s boy hardly stopped. In fact, he ran with all the strength he could muster, stumbling through irrigation ditches, over other crops and through the hedgerows. The farm boy called after him, chasing him on his heels. Though as the leg irons rubbed against the general’s boy’s calloused ankles, they almost tripped him when he scrambled into a barn.

“I know you’re in there,” the farm boy called out. He poked into the stalls to find him. But the general’s boy had ducked behind the horse trough, watching him walk by. “You can’t hide.”

Willing to take his chances that he could, the general’s boy crawled through the gap under the trough and crept back out of the barn the moment the farm boy’s back was to him. As soon as the general’s boy had walked far enough, he ran again, ducking through the berry bushes towards town.

There he found a shed and also a fruit cellar. Crawling through the strung-up bushes of raspberries, the general’s boy looked back only once. He could see the farm boy come out of the barn and cup his hands around his mouth.

“I’m gonna find you! You can’t hide from me!”

The general’s boy ducked behind the shed and peered around the corner. He had seen a few fruit pickers in the groves ahead of him gathering peaches. There were a number of them in aprons and hats with gloves on. The girls trailed after the older women, carrying the bushels towards the road where a horse cart waited to collect the bushels. The driver waited in his seat with a patient worn look on his wrinkled face. Peering through the trees, the boy contemplated the possibility of riding into the town on this cart, but there was no way he could do it if everyone was going to recognize him as the general’s missing property.

Searching for a way out, his eyes set on a pair of trousers hanging on a nail from the fruit cellar wall where a number of baskets were hanging. Creeping forward, he saw that there were not just trousers, but a shirt for a man, a work hat, and an apron—all three somewhat damp. Grabbing them all, he pulled back into the space he had been hiding. He tore off his ratty side-laced trousers then climbed into the large, but not uncomfortably so, pants he had taken. All the while, that farm boy call out after him not far off.

Tying the waist straps so that the pants hung snug on his body, the general’s boy then quickly drew the shirt over his head and pulled his arms through the sleeves. Tucking the shirt in and rolling up the sleeves to his elbows, he quickly yanked on the hat, tucking all his stray hair in. He had to roll up his pant cuffs so that he wasn’t walking on them. But when he was done, he took a breath to look calm so he could merely stroll through the trees to pass the workers as if he belonged there—or at least he hoped he looked it. Stuffing his dagger into the deep pocket along with his family seal, he drew in a breath.

“I know you are here!” The farm boy called, coming closer to the orchard.

“What are you doing here?” A woman snapped at the farm boy, reaching out to box his ears.

The farm boy ducked, holding his hayfork back like a staff. “Nothin’. I just—”

“You’re supposed to be busy with haying.” The woman grabbed his ear instead, yanking on it. “Now get!”

That boy stomped back. He hung his shoulders with a sulk. “But I saw that slave boy on those posters out in the hay fields. I chase him to the barn, but he snuck out.”

“No making up stories, Todas. Now get, or I’ll sick your father on you for lollygagging.” She kicked at him.

“All right!” The boy stomped back towards the hay fields. “But I heard he’s worth a lot of money!”

“I said get!”

He ran off, but he stuck his tongue out at her before really going.

“Good for nothing troublemaker.” She turned and muttered to the girls she was working with while the general’s boy continued walking through the trees to the road, glancing back at her once. “Even if that boy was here, how dare he think to turn him in for the money?”

“It’s a lot of money,” the girl carrying the bushel at her right said.

The woman struck the back of the girl’s head with the flat of her hand. “Don’t talk like that! It’s a human being that they’re asking for. Not a missing cow. I feel sorry for the poor kid.”

The other girl lifted her chin and said, “He’s got to be brave to run from General Gole.”

“And don’t you let anyone hear talking like that either,” the woman said, though milder as if she agreed with the sentiment. “If those blue-eyes hear it, they might string you up and stick you in the stocks.”

Both girls exchanged glances, but they also closed their mouths.

The general’s boy veered away from them, deciding against riding in the cart after all. Keeping the fruit pickers in view in the corner of his eye, he reached the road. He looked beyond it to the town on the hill and drew in a breath. Then he crossed, looking both ways, knowing how fast automobiles could come and go in town areas.

It was a long walk to the town from the fields, but he took his time so he would not appear rushed. The horse drawn carts, the automobiles, and the trucks passed him by without even a look. People on foot walked in the dust at the sides, crossing the train tracks and entering the commerce district without so much as a checkpoint. Though, the Sky Child soldiers did watch the people enter the merchandise square, probably checking for weapons. For a moment he worried that they might discover his dagger. He held it underneath his hand in his deep pants pocket, laying it flat against his leg. But the soldiers hardly looked at him at all. They stopped a cart instead to speak with the driver.

Entering the commerce district, almost automatically he went into his familiar routine of ducking down and walking quickly as he did when running an errand for the general. He passed the shops that sold hats, leather purses and boots with laces and silver buckles, going around shoppers who had slaves to carry their bags. He wove through the stands that sold clothing for the middleclass, some of the sellers calling for him to buy. But he did not stop. Walking through all the sellers and buyers to the market street where servants from households gathered up the fresh vegetables and fruits, he hurried by people counting eggs and chops of meat for the suppers that evening. The smell of spices and warm bread steamed up from the bamboo baskets and out of the ovens. The breads were lifted on trays where scullery maids bartered the price with the bakers. Fighting his hunger as he licked the saliva from his lips, he continued on until he reached the living areas. Here he slowed down.

The living areas for humans among the lower class had the typical wooden homes with walkways. Peering in them, he saw the clean streets that was usual for a northern town, putting Roan to shame. The people here were conscientious. The women here scrubbed the walk in front of their homes like they would have done in his home village. A pang struck him as he wondered once more if his mother was alive.

Sitting down on the edge of the walkway along the road between the living quarters and the market, he exhaled and hunched over his shoulders. There was nothing else he could do until he figured out where he could find the raiders that used to visit his father’s shop. Though he was hungry, he knew if he stole food it would only bring the attention of others. He had to be the watcher. But it was one thing he was good at. By watching, he had gained knowledge of the ways of the Sky Children, enough to know how to avoid them. It was the only way he knew to find those he was looking for.

*

He hated waiting. Gailert was tired of waiting. He had spent the past few weeks just waiting for reports on their progress in the corner. So far, the news was neither bad nor good. And since the captains all agreed he was safest in Barnid Town, he no longer traveled with caravans sent to fight the insurgents.

What he hated the most about it was becoming a back-seat general. He had always been on the front lines fighting against the enemy. But everyone was agreed that at his age he ought to start to take it easy. But sitting and waiting was not his style.

Perhaps that was why he decided to take a walk. His new boy walked after him, eagerly keeping up pace. The child was so much better than his last boy that Gailert didn’t even need to chain this boy’s ankles. In fact, the general doted on the child. He gave him a better place to sleep, and he had the boy eating hearty meals to bring up his strength. And when he was very good, Gailert allowed the boy to sit up in the library with him as he read from his books. But on his walk, Gailert trotted fast, and the child struggled to keep up—not whining or complaining, but the puffs of his breath showed that he was having difficulty with it.

“Ah! General Winstrong!” The mayor of Barnid waved from his auto as he had his driver stop on the curb. “I have been meaning to talk with you!”

Halting, the general gave the mayor a bow. “Your Honor.”

Leaning out of the window, the mayor grinned from ear

Comments (0)