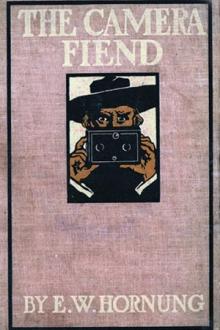

The Camera Fiend, E. W. Hornung [important of reading books txt] 📗

- Author: E. W. Hornung

- Performer: -

Book online «The Camera Fiend, E. W. Hornung [important of reading books txt] 📗». Author E. W. Hornung

“No—yourself.”

“Then I can!”

The doctor overcame his final hesitation.

“Do you remember a man we left behind us on the grass?”

“Perfectly; the grass looked as wet as it felt just now in my dream.”

“Exactly. Didn't it strike you as strange that he should be lying there in the wet grass?”

“I thought he was drunk.”

[pg 75]“He was dead!”

Pocket was shocked; he was more than shocked, for he had never witnessed death before; but next moment the shock was uncontrollably mitigated by a sudden view of the tragic incident as yet another adventure of that adventurous night. No doubt one to retail in reverential tones, but a most thrilling adventure none the less. He only failed to see why it should affect him as much as the doctor suggested. True, he might be called as witness at the inquest; his very natural density was pierced with the awkward possibility of that. But then he had not even known the man was dead.

Had the doctor?

Yes.

Pocket wondered why he had not been told at the time, but asked another question first.

“What did he die of?”

“A bullet!”

“Suicide?”

“No.”

“Not murder?”

“This paper says so.”

“Does it say who did it?”

“It cannot.”

“Can you?”

“Yes!”

“Tell me.”

[pg 76]The doctor threw out both hands in a despairing gesture.

“Have I to tell you outright, my young fellow, that you did it yourself?”

His overwhelming horror was not alleviated by a moment's doubt. He marvelled rather that he had never guessed what he had done. The walking in his sleep, the shot that woke him, the first words of Dr. Baumgartner, his first swift action, and the warm pistol in his own unconscious hand: these burning memories spoke more eloquently than any words. They would have told their own tale at once, if only he had known the man was dead. Why had he been deceived? It was cruel, it was infamous, to have kept the truth from him for a single instant. Thus wildly did the stricken youth turn and rend his benefactor for the very benefaction of a day's rest in ignorance of his deed. The doctor defended himself firmly, frankly, with much patience and some cynicism. Pocket was reminded of the state he himself had been in at the time. He also might have been a dying [pg 77] man, he was assured, and could well believe on looking back. Baumgartner had actually opened his lips to tell him the truth, but had checked himself in sheer humanity. Again the boy could confirm the outward detail out of his own recollection. To have told him later in the morning, the doctor went on to say, with an emphasis not immediately understood, could have undone nothing. He acknowledged a grave responsibility, but rightly or wrongly he had put the living before the dead.

How had he known the man was dead? Baumgartner smiled at the question. He was not only a doctor, but an old soldier who had fought in one at least of the bloodiest battles in European history. He had seen too many men fall shot through the heart to be mistaken for a moment; but in point of fact he had confirmed his conviction by brief examination while Pocket was fetching his things from behind the bush. Pocket pressed for earlier details with a morbid appetite which was not gratified without reluctance, and out of a laconic interchange the deed was gradually reconstructed with appealing verisimilitude. It was Baumgartner who had first caught sight of the somnambulist, treading warily like the blind, yet waving the revolver as he went, as though any moment he might let it off. The moment came with a wretched reeling man who joined [pg 78] Baumgartner on the path, and would not be warned. The poor man had raised a drunken shout and been shot pointblank through the heart. The doctor described him as leaping backward from the levelled barrel, then into the air and down in the dew upon his face.

The boy buried his face and wept; but even in his anguish he now recalled the shout before the shot. The enforced description had been so vivid in the end that he beheld the scene as plainly as though he had been wide awake. Then he dwelt upon the dead man, looking nothing else as he now remembered him, and that sent him off at a final tangent.

He cried, looking up with a shudder for all his tears, “What about that negative you smashed? It was the poor dead man all the time!”

“It was,” replied Baumgartner; “but it was never meant to be. I had you in focus when you fired. What I did was done instinctively, but with time to think I should have done just the same. You had given me the chance of a lifetime, though nothing has come of it so far. And that was another reason for saving you, ill as you were, from the immediate consequences of an innocent act.”

Pocket was passionately honest, as his worst friends knew; he had an instinctive admiration [pg 79] for downright honesty in another. His young soul was torn with grief and pity for the dead; he was already haunted by the inevitable and complex consequences of his fatal misadventure, and yet he could dimly appreciate the candid declaration of one who had attempted to turn that tragedy to instantaneous and inconceivable account. It was the mistaken kindness to himself that he still found most difficult to forgive.

“It's got to come out,” he groaned; “this will make it all the worse.”

“You mean the delay?”

“Yes! Who's to tell them I didn't do it on purpose, and run away, and then think better of it?”

Baumgartner smiled.

“Surely I am,” said he; but his smile went out with the words. “If only they believe me!” he added as though it was a new idea to him.

It was a terrifying one to Pocket.

“Why shouldn't they?” was his broken exclamation.

“I don't know. I never thought of it before. But what can I swear to, after all? I can swear you shot a man, but I can't swear you shot him in your sleep!”

“You said you saw I did!”

“So I did, my young fellow,” replied the doctor, [pg 80] with a kinder smile; “at least I can swear that you were walking with your eyes shut, and I thought you were walking in your sleep. It's not quite the same thing. It is near it. But we are talking about my evidence on oath in a court of justice.”

“Shall I be tried?” asked the schoolboy in a hoarse whisper.

“Perhaps only by the magistrate,” replied the other, soothingly; “let us hope it will stop at that.”

“But it must, it must!” cried Pocket wildly. “I'm absolutely innocent! You said so yourself a minute ago; you've only to swear it as a doctor? They can't do anything to me—they can't possibly!”

The doctor stood looking into the sunless garden with a troubled face.

“Dr. Baumgartner!”

“Yes, my young fellow?”

“They can't do anything to me, can they?”

Baumgartner returned to the fireside with his foreign shrug.

“It depends what you call anything,” said he. “They cannot hang you; after what I should certainly have to say I doubt if they could even detain you in custody. But you would only be released on bail; the case would be sent for trial; it would get into every paper in England; your family could not stop it, your schoolfellows would [pg 81] devour it, you would find it difficult to live down both at home and at school. In years to come it will mean at best a certain smile at your expense! That is what they can do to you,” concluded the doctor, apologetically. “You asked me to tell you. It is better to be candid. I hoped you would bear it like a man.”

Pocket was not even bearing it like a manly boy; he had flung himself back into the big chair, and broken down for the first time utterly. One name became articulate through his sobs. “My mother!” he moaned. “It'll kill her! I know it will! Oh, that I should live to kill my mother too!”

“Mothers have more lives than that; they have more than most people,” remarked Baumgartner sardonically.

“You don't understand! She has had a frightful illness, bad news of any kind has to be kept from her, and can you imagine worse news than this? She mustn't hear it!” cried the boy, leaping to feet with streaming eyes. “For God's sake, sir, help me to hush it up!”

“It's in the papers already,” replied Baumgartner, with a forbearing shrug.

“But my part in it!”

“You said it had got to come out.”

“I didn't realise all it meant—to her!”

[pg 82]“I thought you meant to make a clean breast of it?”

“So I did; but now I don't!” cried Pocket, vehemently. “Now I would give my own life, cheerfully, rather than let her know what I've done—than drag them all through that!”

“Do you mean what you say?”

Baumgartner appeared to be forming some conditional intention.

“Every syllable!” said Pocket.

“Because, you know,” explained the doctor, “it is a case of now or never so far as going to Scotland Yard is concerned.”

“Then it's never!”

“I must put it plainly to you. It's not too late to do whatever you decide, but you must decide now. I would still go with you to Scotland Yard, and the chances are that they would still accept the true story of to-day. I have told you what I believe to be the worst that can happen to you; it may be that rather more may happen to me for harbouring you all day as I have done. I hope not, but I took the law into my own hands, and I I am prepared to abide by the law if you so decide this minute.”

Comments (0)