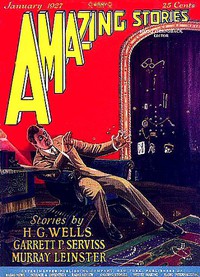

The Red Dust, Murray Leinster [best book reader txt] 📗

- Author: Murray Leinster

Book online «The Red Dust, Murray Leinster [best book reader txt] 📗». Author Murray Leinster

Burl believed that the rustling was merely the sound of a moth or butterfly emerging from its chrysalis, but was unwilling to take any chances. He and his people circled the mushroom thicket and mounted higher.

And at last, perhaps six or seven hundred feet above the level of the river, they came upon a little plateau, going back into a small pocket in the mountainside. Here they found many of the edible fungoids, and no less than a dozen of the giant cabbages, on whose broad leaves many furry grubs were feeding steadily in placid contentment with themselves and all the world.

A small stream bubbled up from a tiny basin and ran swiftly across the plateau, and there were dense thickets of toadstools in which the tribesmen might find secure hiding-places. The tribe would make itself a new home here.

That night they hid among inextricably tangled masses of mushrooms, and saw with amazement the multitude of creatures that ventured forth in the darkness. All the valley and the plateau were illumined by the shining beacons of huge but graceful fireflies, who darted here and there in delight and—apparently—in security.

Upon the earth below, also, many tiny lights glowed. The larv� of the fireflies crawled slowly but happily over the fungus-covered mountainside, and great glow-worms clambered upon the shining tops of the toadstools and rested there, twin broad bands of bluish fire burning brightly within their translucent bodies.

They were the females of the firefly race, which never attain to legs and wings, but crawl always upon the earth, merely enlarged creatures in the forms of their own larv�. Moths soared overhead with mighty, throbbing wing-beats, and all the world seemed a paradise through which no evil creatures roamed in search of prey.

And a strange thing came to pass. Soon after darkness fell upon the earth and the steady drip-drop of the rain began, a musical tinkling sound was heard which grew in volume, and became a deep-toned roar, which reechoed and reverberated from the opposite hillsides until it was like melodious and long-continued thunder. For a long time the people were puzzled and a little afraid, but Burl took courage and investigated.

He emerged from the concealing thicket and peered cautiously about, seeing nothing. Then he dared move in the direction of the sound, and the gleam from a dozen fireflies showed him a sheet of water pouring over a vertical cliff to the river far below.

The rainfall, gentle as it was, when gathered from all the broad expanse of the mountainside, made a river of its own, which had scoured out a bed, and poured down each night to plunge in a smother of spray and foam through six hundred feet of empty space to the swiftly flowing river in the center of the valley. It was this sound that had puzzled the tribefolk, and this sound that lulled them to sleep when Burl at last came back to allay their fears.

The next day they explored their new territory with a boldness of which they would not have been capable a month before. They found a single great trap-door in the earth, sure sign of the burrow of a monster spider, and Burl resolved that before many days the spider would be dealt with. He told his tribesmen so, and they nodded their heads solemnly instead of shrinking back in terror as they would have done not long since.

The tribe was rapidly becoming a group of men, capable of taking the aggressive. They needed Burl's rash leadership, and for many generations they would need bold leaders, but they were infinitely superior to the timid, rabbit-like creatures they had been. They bore spears, and they had used them. They had seen danger, and had blindly followed Burl through the forest of strangled things instead of fleeing weakly from the peril.

They wore soft, yellow fur about their middles, taken from the bodies of giant slugs they had slain. They had eaten much meat, and preferred its succulent taste to the insipid savor of the mushrooms that had once been their steady diet. They knew the exhilaration of brave adventure—though they had been forced into adventure by Burl—and they were far more worthy descendants of their ancestors than those ancestors had known for many thousand years.

The exploration of their new domain yielded many wonders and a few advantages. The tribefolk found that the nearest ant-city was miles away, and that the small insects would trouble them but rarely. (The nightly rush of water down the sloping sides of the mountain made it undesirable for the site of an ant colony.)

And best of all, back in the little pocket in the mountainside, they found old and disused cells of hunting wasps. The walls of the pocket were made of soft sandstone with alternate layers of clay, and the wasps had found digging easy.

There were a dozen or more burrows, the shaft of each some four feet in diameter and going back into the cliff for nearly thirty feet, where they branched out into a number of cells. Each of the cells had once held a grub which had grown fat and large upon its hoard of paralyzed crickets, and then had broken away to the outer world to emerge as a full-grown wasp.

Now, however, the laboriously tunneled caverns would furnish a hiding-place for the tribe of men, a far more secure hiding-place than the center of the mushroom thickets. And, furthermore, a hiding-place which, because more permanent, would gradually become a possession for which the men would fight.

It is a curious thing that the advancement of a people from a state of savagery and continual warfare to civilization and continual peace is not made by the elimination of the causes of strife, but by the addition of new objects and ideals, in defense of which that same people will offer battle.

A single chrysalis was found securely anchored to the underside of a rock-shelf, and Burl detached it with great labor and carried it into one of the burrows, though the task was one that was almost beyond his strength. He desired the butterfly that would emerge for his own use.

He preempted, too, a solitary burrow a little distant from the others, and made preparations for an event that was destined to make his plans wiser and more far-reaching than before.

His followers were equally busy with their various burrows, gathering stores of soft growth for their couches, and later—at Burl's suggestion—even carrying within the dark caverns the radiant heads of the luminous mushrooms to furnish illumination. The light would be dim, and after the mushroom had partly dried it would cease, but for a people utterly ignorant of fire it was far from a bad plan.

Burl was very happy for that time. His people looked upon him as a savior, and obeyed his least order without question. He was growing to repose some measure of trust in them, too, as men who began to have some glimmerings of the new-found courage that had come to him, and which he had striven hard to implant in their breasts.

The tribe had been a formless gathering of people. There were six or seven men and as many women, and naturally families had come into being—sometimes after fierce and absurd fights among the men—but the families were not the sharply distinct agreements they would have been in a tribe of higher development.

The marriage was but an agreement, terminable at any time, and the men had but little of the feeling of parenthood, though the women had all the fierce maternal instinct of the insects about them.

These burrows in which the tribefolk were making their homes would put an end to the casual nature of the marriage bonds. They were homes in the making—damp and humid burrows without fire or heat, but homes, nevertheless. The family may come before the home, in the development of mankind, but it invariably exists when the home has been made.

The tribe had been upon the plateau for nearly a week when Burl found that stirrings and strugglings were going on within the huge cocoon he had laid close beside the burrow he had chosen for his own. He cast aside all other work, and waited patiently for the thing he knew was about to happen. He squatted on his haunches beside the huge, oblong cylinder, his spear in his hand, waiting patiently. From time to time he nibbled at a bit of edible mushroom.

Burl had acquired many new traits, among which a little foresight was most prominent, but he had never conquered the habit of feeling hungry at any and every time that food was near at hand. He had to wait. He had food. Therefore, he ate.

The sound of scrapings came from the closed cocoon, caked upon its outer side with dirt and mold. The scraping and scratching continued, and presently a tiny hole showed, which rapidly enlarged. Tiny jaws and a dry, glazed skin became visible, the skin looking as if it had been varnished with many coats of brown shellac. Then a malformed head forced its way through and stopped.

All motion ceased for a matter of perhaps half an hour, and then the strange, blind head seemed to become distended, to be swelling. A crack appeared along its upper part, which lengthened and grew wide. And then a second head appeared from within the first.

This head was soft and downy, and a slender proboscis was coiled beneath its lower edge like the trunk of one of the elephants that had been extinct for many thousand years. Soft scales and fine hairs alternated to cover it, and two immense, many-faceted eyes gazed mildly at the world on which it was looking for the first time. The color of the whole was purest milky-white.

Slowly and painfully, assisting itself by slender, colorless legs that seemed strangely feeble and trembling, a butterfly crawled from the cocoon. Its wings were folded and lifeless, without substance or color, but the body was a perfect white. The butterfly moved a little distance from its cocoon and slowly unfurled its wings. With the action, life seemed to be pumped into them from some hidden spring in the insect's body. The slender antenn� spread out and wavered gently in the warm air. The wings were becoming broad expanses of snowy velvet.

A trace of eagerness seemed to come into the butterfly's actions. Somewhere there in the valley sweet food and joyous companions awaited it. Fluttering above the fungoids of the hillsides, surely there was a mate with whom the joys of love were to be shared, surely upon those gigantic patches of green, half hidden in the haze, there would be laid tiny golden eggs that in time would hatch into small, fat grubs.

Strength came to the butterfly's limbs. Its wings were spread and closed with a new assurance. It spread them once more, and raised them to make the first flight of this new existence in a marvelous world, full of delights and adventures—Burl struck home with his spear.

The delicate limbs struggled in agony, the wings fluttered helplessly, and in a little while the butterfly lay still upon the fungus-carpeted earth, and Burl leaned over to strip away the great wings of snow-white velvet, to sever the long and slender antenn�, and then to call his tribesmen and bid them share in the food he had for them.

And there was a feast that afternoon. The tribesmen sat about the white carcass, cracking open the delicate limbs for the meat within them, and Burl made sure that Saya secured the choicest bits. The tribesmen were happy. Then one of the children of the tribe stretched a hand aloft and pointed up the mountainside.

Coming slowly down the slanting earth was a long, narrow file of living animals. For a time the file seemed to be but one creature, but Burl's keen eyes soon saw that there were many. They were caterpillars, each one perhaps ten feet long, each with a tiny black head armed with sharp jaws, and with dull-red fur upon their backs. The rear of the procession was lost in the mist of the low-hanging cloud-banks that covered the mountainside some two thousand feet above the plateau, but the foremost was no more than three hundred yards away.

Slowly and solemnly the procession came on, the black head of the second touching the rear of the first, and the head of the third touching the rear of the second. In faultless alignment, without intervals, they moved steadily down the slanting side of the mountain.

Save the first, they seemed absorbed in maintaining their perfect formation, but the leader constantly rose upon his hinder half and waved the fore part of his body in

Comments (0)