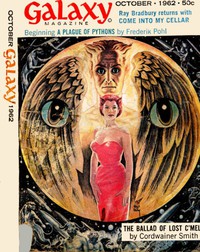

Plague of Pythons, Frederik Pohl [top 100 novels .txt] 📗

- Author: Frederik Pohl

Book online «Plague of Pythons, Frederik Pohl [top 100 novels .txt] 📗». Author Frederik Pohl

The maimed victims at the Monument supplied a clue, of course. He could not really believe that that sort of punishment would be applied for minor infractions. Death was so much less trouble. Even death was not really likely, he thought, for a simple lapse.

He thought.

He could not be sure, of course. He could be sure of only one thing: He was now a slave, completely a slave, a slave until the day he died. Back on the mainland there was the statistical likelihood of occasional slavery-by-possession, but there it was only the body that was enslaved, and only for moments. Here, in the shadow of the execs, it was all of him, forever, until death or a miracle turned him loose.

On the second day following he returned to his room at Tripler after breakfast, and found a Honolulu city policeman sitting hollow-eyed on the edge of his bed. The man stood up as Chandler came in. "So," he grumbled, "you take so long! Here. Is diagrams, specs, parts lists, all. You get everything three days from now, then we begin."

The policeman, no longer Koitska, shook himself, glanced stolidly at Chandler and walked out, leaving a thick manila envelope on the pillow. On it was written, in a crabbed hand: All secret! Do not show diagrams!

Chandler opened the envelope and spilled its contents on the bed.

An hour later he realized that sixty minutes had passed in which he had not been afraid. It was good to be working again, he thought, and then that thought faded away again as he returned to studying the sheaves of circuit diagrams and closely typed pages of specifications. It was not only work, it was hard work, and absorbing. Chandler knew enough about the very short wavelength radio spectrum to know that the device he was supposed to build was no proficiency test; this was for real. The more he puzzled over it the less he could understand of its purpose. There was a transmitter and there was a receiver. Astonishingly, neither was directional: that ruled out radar, for example. He rejected immediately the thought that the radiation was for spectrum analysis, as in the Caltech project—unfortunate, because that was the only application with which he had first-hand familiarity; but impossible. The thing was too complicated. Nor could it be a simple message transmitter—no, perhaps it could, assuming there was a reason for using the submillimeter bands instead of the conventional, far simpler short-wave spectrum. Could it? The submillimeter waves were line-of-sight, of course, but would ionosphere scatter make it possible for them to cover great distances? He could not remember. Or was that irrelevant, since perhaps they needed only to cover the distances between islands in their own archipelago? But then, why all the power? And in any case, what about this fantastic switching panel, hundreds of square feet of it even though it was transistorized and subminiaturized and involving at least a dozen sophisticated technical refinements he hadn't the training quite to understand? AT&T could have handled every phone call in the United States with less switching than this—in the days when telephone systems spanned a nation instead of a fraction of a city. He pushed the papers together in a pile and sat back, smoking a cigarette, trying to remember what he could of the theory behind submillimeter radiation.

At half a million megacycles and up, the domain of quantum theory began to be invaded. Rotating gas molecules, constricted to a few energy states, responded directly to the radio waves. Chandler remembered late-night bull sessions in Pasadena during which it had been pointed out that the possibilities in the field were enormous—although only possibilities, for there was no engineering way to reach them, and no clear theory to point the way—suggesting such strange ultimate practical applications as the receiverless radio, for example. Was that what he had here?

He gave up. It was a question that would burn at him until he found the answer, but just now he had work to do, and he'd better be doing it.

Skipping lunch entirely, he carefully checked the components lists, made a copy of what he would need, checked the original envelope and its contents with the man at the main receiving desk for his safe, and caught the bus to Honolulu.

At the Parts 'n Plenty store, Hsi read the list with a faint frown that turned into a puzzled scowl. When he put it down he looked at Chandler for a few moments without speaking.

"Well, Hsi? Can you get all this for me?" The parts man shrugged and nodded. "Koitska said in three days."

Hsi looked startled, then resigned. "That puts it right up to me, doesn't it? All right. Wait a moment."

He disappeared in the back of the store, where Chandler heard him talking on what was evidently an intercom system. He came back in a few minutes and slipped Chandler's list into a slit in the locked door. "Tough for Bert," he said. "He'll be working all night, getting started—but I can take it easy till tomorrow. By then he'll know what we don't have, and I'll find some way to get it." He shrugged again, but his face was lined. Chandler wondered how one went about finding, for example, a thirty megawatt klystron tube; but it was Hsi's problem. He said:

"All right, I'll see you Monday."

"Wait a minute, Chandler." Hsi eyed him. "You don't have anything special to do, do you? Well, come have dinner with me. Maybe I can get to know you. Then maybe I can answer some of your questions, if you like."

They took a bus out Kapiolani Boulevard, then got out and walked a few blocks to a restaurant named Mother Chee's. Hsi was well known there, it seemed. He led Chandler to a booth at the back, nodded to the waiter, ordered without looking at the menu and sat back. "You malihinis don't know much about food," he said, humorously patronizing. "I think you'll like it. It's all fish, anyway."

The man was annoying. Chandler was moved to say, "Too bad, I was hoping for duck in orange sauce, perhaps some snow peas—"

Hsi shook his head. "There's meat, all right, but not here. You'll only find it in the places where the execs sometimes go.... Tell me something, Chandler. What's that scar on your forehead."

Chandler touched it, almost with surprise. Since the medics had treated it he had almost forgotten it was there. He began to explain, then paused, looking at Hsi, and changed his mind. "What's the score? You testing me, too? Want to see if I'll lie about it?"

Hsi grinned. "Sorry. I guess that's what I was doing. I do know what an 'H' stands for; we've seen them before. Not many. The ones that do get this far usually don't last long. Unless, of course, they are working for somebody whom it wouldn't do to offend," he explained.

"So what you want to know, then, is whether I was really hoaxing or not. Does it make any difference?"

"Damn right it does, man! We're slaves, but we're not animals!" Chandler had gotten to him; the parts man looked startled, then sallow, as he observed his own vehemence.

"Sorry, Hsi. It makes a difference to me, too. Well, I wasn't hoaxing. I was possessed, just like any other everyday rapist-murderer, only I couldn't prove it. And it didn't look too good for me, because the damn thing happened in a pharmaceuticals plant. That was supposed to be about the only place in town where you could be sure you wouldn't be possessed, or so everybody thought. Including me. Up to the time I went ape."

Hsi nodded. The waiter approached with their drinks. Hsi looked at him appraisingly, then did a curious thing. He gripped his left wrist with his right hand, quickly, then released it again. The waiter did not appear to notice. Expertly he served the drinks, folded small pink floral napkins, dumped and wiped their ashtray in one motion—and then, so quickly that Chandler was not quite sure he had seen it, caught Hsi's wrist in the same fleeting gesture just before he turned and walked away.

Without comment Hsi turned back to Chandler. He said, "I believe you. Would you like to know why it happened? Because I think I can tell you. The execs have all the antibiotics they need now."

"You mean—" Chandler hesitated.

"That's right. They did leave some areas alone, as long as they weren't fully stocked on everything they might want for the foreseeable future. Wouldn't you?"

"I might," Chandler said cautiously, "if I knew what I was—being an exec."

Hsi said, "Eat your dinner. I'll take a chance and tell you what I know." He swallowed his whiskey-on-the-rocks with a quick backward jerk of the head. "They're mostly Russians—you must know that much for yourself. The whole thing started in Russia."

Chandler said, "Well, that's pretty obvious. But Russia was smashed up as much as anywhere else. The whole Russian government was killed—wasn't it?"

Hsi nodded. "They're not the government. Not the exec. Communism doesn't mean any more to them than the Declaration of Independence does—which is nothing. It's very simple, Chandler: they're a project that got out of hand."

Back four years ago, he said, in Russia, it started in the last days of the Second Stalinite Regime, before the Neo-Krushchevists took over power in the January Push.

The Western World had not known exactly what was going on, of course. The "mystery wrapped in a riddle surrounded by an enigma" had become queerer and even more opaque after Kruschchev's death and the revival of such fine old Soviet institutions as the Gay Pay Oo. That was the development called the Freeze, when the Stalinites seized control in the name of the sacred Generalissimo of the Soviet Fatherland, a mighty-missile party, dedicated to bringing about the world revolution by force of sputnik. The neo-Krushchevists, on the other hand, believed that honey caught more flies than vinegar; and, although there were few visible adherents to that philosophy during the purges of the Freeze, they were not all dead. Then, out of the Donbas Electrical Workshop, came sudden support for their point of view.

It was a weapon. It was more than a weapon, an irresistable tool—more than that, the way to end all disputes forever. It was a simple radio transmitter (Hsi said)—or so it seemed, but its frequencies were on an unusual band and its effects were remarkable. It controlled the minds of men. The "receiver" was the human brain. Through this little portable transmitter, surgically patch-wired to the brain of the person operating it, his entire personality was transmitted in a pattern of very short waves which could invade and modulate the personality of any other human being in the world. For that matter, of any animal, as long as the creature had enough "mind" to seize—

"What's the matter?" Hsi interrupted himself, staring at Chandler. Chandler had stopped eating, his hand frozen midway to his mouth. He shook his head.

"Nothing. Go on." Hsi shrugged and continued.

While the Western World was celebrating Christmas—the Christmas before the first outbreak of possession in the outside world—the man who invented the machine was secretly demonstrating it to another man. Both of them were now dead. The inventor had been a Pole, the other man a former Party leader who, four years before, had rescued the inventor's dying father from a Siberian work camp. The Party leader had reason to congratulate himself on that loaf cast on the water. There were only three working models of the transmitter—what ultimately was refined into the coronet Chandler had seen on the heads of Koitska and the girl—but that was enough for the January push.

The Stalinites were out. The neo-Krushchevists were in.

A whole factory in the Donbas was converted to manufacturing these little mental controllers as fast as they could be produced—and that was fast, for they were simple in design to begin with and were quickly refined to a few circuits. Even the surgical wiring to the brain became unnecessary as induction coils tapped the encephalic rhythms. Only the great amplifying hookup was really complicated. Only one of those was necessary, for a single amplifier could serve as re-broadcaster—modulator for thousands of the headsets.

"Are you sure you're all right?" Hsi demanded.

Chandler put down his fork, lit a cigarette and beckoned to the waiter. "I'm all right. I just want another drink."

He needed the drink. For now he knew what he was building for Koitska.

The waiter brought two more drinks and carried away the uneaten food. "We don't know exactly who did what after that," Hsi said, "but somehow or other

Comments (0)