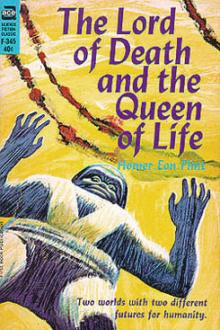

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [some good books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [some good books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

"I stay here," said she in the same clear voice, entirely unshaken by my presence. "Edam hath claimed me, and I shall cleave to him. I want none of ye, ye giant!"

For a moment I was minded to throw my weight against the barrier, such was my rage. Then I thought better on it, and closely examined the bars. Two were loose.

"Ave," said I, contriving to keep my voice even, although my hands were busy with the bars as I spake. "Ave—ye do wrong to spite me thus. Know ye not that I am the emperor, and that these bars cannot stand before me? I warn ye, if I must call my men to help me, and to witness my shame, it will go hard with ye! Better that ye should come willingly. Ye are not for such as Edam."

"No?" quoth the young man, speaking up for the chit. "Ye are wrong, Strokor. We defy thee to do thy worst; we are prepared to flee from ye at all costs!"

I had twisted one of the bars out of my way without their seeing it. I strove at the next as I answered, still controlling my voice: "'Twill do ye no good to flee, Edam; ye know that. And as for Ave—she shall wish she had never been born!"

"So I should," she replied with spirit, "if I were to become thy woman. But know you, Strokor, that Ave, the daughter of Durok, would rather die than take the name of one who had spurned her, as ye did me!"

So I had; it had slipped my mind. "But I want thee now, Ave," said I softly, preparing to slip through the opening I had made. "Surely ye would not take thine own life?"

"Nay," she answered, with a laugh in her voice. "Rather I would go with Edam here. I would go," she finished, her voice rising in her excitement, "away from this horrible man's world; away from it all, Strokor, and to Jeos! Hear ye? To Jeos! And—"

But at that instant I burst through the grating. Without a sound I charged straight for the pair of them. And without a sound they slipped away from before my grasp. Next second I was gazing stupidly at the rushing, swirling water of the flume.

And I saw that they had been sitting in the cabin of a tiny boat, and that they had got away!

There was an opening into the outer air; I rushed through, and stared in the growing twilight down the black furrow of the flume. Far in the distance, and going like a streak, I spied the glittering glass windows of the little craft. Once I made out the flutter of a saucy hand.

"We shall get them when they reach the valley!" I shouted to the men. Then I reached for my tube, and sighted it on the lower end of the flume, far, far below, almost too far away to be clear to the naked eye.

In an incredibly short time the craft reached the end. It traveled at an extraordinary rate; perchance 'twas weighted; I marveled that its windows could stand the force of the air. And I scarce had time to fear that the twain should be destroyed on that upturned spillway before it was there.

And then an awesome thing happened. As the boat struck the incline it shot upward into the air at a steep slant. Up, up it went; my heart jumped into my mouth; for surely they must be crushed when they came down.

But the craft did not come down. It went on and on, up and up; its speed scarcely slackened; 'twas like that of a shooting star. And in far less time than it takes to tell it, the little boat was high up among the stars, going higher every instant, and farther away from me. And suddenly the sweat broke cold on my forehead; for dead ahead, directly in line with their travel, lay the bluish white gleam of Jeos.

So great was my rage over the escape of the dreamer with my woman, at first I felt no sorrow. Later, after days and days of search in and about the basin, I came to grieve most terribly over my loss. When I came home to the palace, I was well-nigh ill.

In vain did I make the most generous of rewards. The whole empire turned out to search for the missing ones, but nothing came of it all. Yet I never ceased to hope, especially after my talk with Maka.

"Aye," he said, when I questioned him, "it were barely possible that they have left this world for all time. I have calculated the speed which their craft might have attained, had it the right proportions, and, in truth, it might have left the spillway at such a speed that it entirely overcame the draw of the ground.

"But I think it were a slim chance. It is more than likely, Strokor, that Ave shall return to thee."

Was I not the fitter man? Surely Edam's purpose could not succeed; Jon would not have it so. The woman was mine, because I had chosen her; and she must come back to me, and in safety, or I should tear Edam into bits.

But as time went on and naught transpired, I became more and more melancholy. Life became an empty thing; it had been empty enough before I had craved the girl, but now it was empty with hopelessness.

After a while I got to thinking of some of the things Maka had told me. The more I thought of the future, the blacker it seemed. True, there were many other women; but there had been only one Ave. No such beauty had ever graced this world before. And I knew I could be happy with no other.

Now I saw that all my fame had been in vain. I had lost the only woman that was fit for me, and when I died there would be naught left but my name. Even that the next emperor might blot out, if he chose. It had all been in vain!

"It shall not be!" I roared to myself, as I strode about my compartment, gnawing at my hands in my misery. And in just such a fit of helpless anger the great idea came to me.

No sooner conceived than put into practice. I will not go closely into details; I will relate just the outstanding facts. What I did was to select a very tall mountain, located almost on the equator, and proclaimed my intention to erect a monument to Jon upon its summit. I caused vast quanities of materials to be brought to the place; and for a year a hundred thousand men labored to put the pieces together.

When they had finished, they had made a mammoth tower partly of wood and partly of alloy. It was made in sections so that it might be placed, piece upon piece, one above another high into the sky.

It was an enormous task. When it was complete, I had a tower as high as the mountain itself erected upon its summit.

And next I caused section after section of the long, iron, pole-to-pole rod, which had tricked Klow, to be hauled up into the tower. I was only careful to begin the process from the top and work downward. I gave word that the last three sections be inserted at midday at a given day.

And at that hour I was safe inside a non-magnetic room.

I know right well when the deed was done. There was a most terrific earthquake. All about me, though I could see nothing at all, I could hear buildings falling. The din was appalling.

At the same time the air was fairly shattered with the rattle of the lightning. Never have I heard the like before. The rod had loosed the wrath of the forces above our air!

And as suddenly the whole deafening storm ended. Perchance the rod was destroyed by the lightning; I never went to see. For I know, the electricity split the very ground apart. But I gazed out of a window in the top of my palace, and saw that I had succeeded.

Not a soul but myself remained alive.

None but buildings made of the alloy were standing. Not only man, but most of his works had perished in that awful blast. I, alone, remained!

I, Strokor, am the survivor! I, the greatest man; it were but fit that I should be the last! No man shall come after me, to honor me or not as he chooses. I, and no other, shall be, the last man!

And when Ave returns—as she must, though it be ages hence—when she comes, she shall find me waiting. I, Strokor, the mighty and wise, shall be here when she returns. I shall wait for her forever; here I shall always stay. The stars may move from their places, but I shall not go! For it is my intention to make use of another secret Maka taught me. In brief—[9]

PART III THE SURVIVORProvided with a sledge-hammer, a crowbar, and a hydraulic jack, and even with drills and explosives as a last resort, Jackson, Kinney, and Van Emmon returned the same day to the walled-in room in the top of that mystifying mansion. The materials they carried would have made considerable of a load had not Smith removed enough of the weights from their suits to offset their burden. They reached the unopened door without special exertion, and with no mishap.

They looked in vain for a crack big enough to hold the point of the crowbar; neither could the most vigorous jabbing loosen any of the material. They dropped that tool and tried the sledge. It got no results; even in the hands of the husky geologist, the most vigorous blows failed to budge the door. They did not even dent it.

So they propped the powerful hydraulic jack, a tool sturdy enough to lift a house, at an angle against the door. Then, using the crowbar as a lever, the architect steadily turned up the screw, the mechanism multiplying his very ordinary strength a hundredfold. In a moment it could be seen that he was getting results; the door began to stir. Van Emmon struck one edge with the sledge-hammer, and it gave slightly.

In another minute the whole door, weighing over a ton, had been pushed almost out of its opening. The jack overbalanced, toppled over; they did not readjust it, but threw their combined weight upon the barrier.

There was no need to try again. With a shiver the huge slab of metal slid, upright, into the space beyond, stood straight on end for a second or so, then toppled to the floor.

And this time they heard the crash.

For, as the door fell, a great gust of wind rushed out with a hissing shriek, almost overbalancing the men from the earth. They stood still for a while, breathing hard from their exertion, trying in vain to peer into the blackness before them. Under no circumstances would either of them have admitted that he was gathering courage.

In a minute the architect, his eyes sparkling with his enthusiasm for the antique, picked up the electric torch and turned it into the compartment. As he did so the other two stepped to his side, so that the three of them faced the unknown together. It was just as well. Outlined in that circle of light, and not six feet in front of them, stood a great chair upon a wide platform; and seated in it, erect and alert, his wide open eyes staring straight into those of the three, was the frightful mountainous form of Strokor, the giant, himself.

For an indeterminable length of time the men from the earth stood there, speechless, unbreathing, staring at that awful monster as though at a nightmare. He did not move; he was entirely at ease, and yet plainly on guard, glaring at them with an air of conscious superiority which held them powerless. Instinctively they knew that the all-dominating voice in the records had belonged to this Hercules. But their instinct could not tell them whether the man still lived.

It was the doctor's brain that worked first. Automatically, from a lifelong habit of diagnosis, he inspected that dreadful figure quite as though it were that of a patient. Bit by bit his subconscious mind pieced together the evidence; the man in the chair showed no signs of life. And after a while the doctor's conscious mind also knew.

"He is dead," he said positively, in his natural voice; and such was the vast relief of the other two that they were in no way startled by the sound. Instantly all three drew long breaths; the tension was relaxed; and Van

Comments (0)