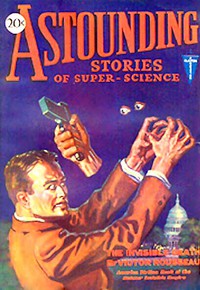

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930, Various [feel good books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930, Various [feel good books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Various

"That is so, sir, and then we shall have the advantage of invisibility, and[46] the enemy ships will be in fluorescence."

"Damned impracticable!" muttered Stopford.

"You seriously propose to darken the greater part of eastern North America?" asked the Secretary for War.

"The gas can be produced in large quantities from coal tar besides existing in crystalline deposits," replied Luke Evans. "It is so volatile that I estimate that a single ton will darken all eastern North America for five days. Whereas the concentration would be made only in specific areas liable to attack. The gas is distilled with great facility from one of the tri-phenyl-carbinol coal-tar derivatives."

Vice-president Tomlinson was a pompous, irascible old man, but it was he who hit the nail on the head.

"That's all very well as an emergency measure, but we've got to find the haunt of that gang and smash it!"

An orderly brought in a telegraphic dispatch and handed it to him. The Vice-president opened it, glanced through it, and tried to hand it to the Secretary of State. Instead, it fluttered from his nerveless fingers, and he sank back with a groan. The Secretary picked it up and glanced at it.

"Gentlemen," he said, trying to control his voice, "New York was bombed out of the blue at sunrise this morning, and the whole lower part of the city is a heap of ruins."

n the days that followed it became clear that all the resources of America would be needed to cope with the Invisible Empire. Not a day passed without some blow being struck. Boston, Charleston, Baltimore, Pittsburg in turn were devastated. Three cruisers and a score of minor craft were sunk in the harbor of Newport News, where they were concentrating, and thenceforward the fleet became a fugitive force, seeking concealment rather than an offensive. Trans-Atlantic sea-traffic ceased.

Meanwhile the black gas was being hurriedly manufactured. From cylinders placed in central positions in a score of cities it was discharged continuously, covering these centers with an impenetrable pall of night that no light would penetrate. Only by the glow of radium paint, which commanded fabulous prices, could official business be transacted, and that only to a very small degree.

Courts were closed, business suspended, prisoners released, perforce, from jails. Famine ruled. The remedy was proving worse than the disease. Within a week the use of the dark gas had had to be discontinued. And a temporary suspension of the raids served only to accentuate the general terror.

There were food riots everywhere, demands that the Government come to terms, and counter-demands that the war be fought out to the bitter end.

Fought out, when everything was disorganized? Stocks of food congested all the terminals, mobs rioted and battled and plundered all through the east.

"It means surrender," was voiced at the Council meeting by one of the members. And nobody answered him.

Three days of respite, then, instead of bombs, proclamations fluttering down from a cloudless sky. Unless the white flag of surrender was hoisted from the summit of the battered Capitol, the Invisible Emperor would strike such a blow as should bring America to her knees!

t was a twelve-hour ultimatum, and before three hours had passed thousands of citizens had taken possession of the Capitol and filled all the approaches. Over their heads floated banners—the Stars and Stripes, and, blazoned across them the words, "No Surrender."

It was a spontaneous uprising of the people of Washington. Hungry, homeless in the sharpening autumn weather, and nearly all bereft of members of[47] their families, too often of the breadwinner, now lying deep beneath the rubble that littered the streets, they had gathered in their thousands to protest against any attempt to yield.

Dick, flying overhead at the apex of his squadron, felt his heart swell with elation as he watched the orderly crowds. This was at three in the afternoon: at six the ultimatum ended, the new frightfulness was to begin.

At five, Vice-president Tomlinson was to address the crowds. The old man had risen to the occasion. He had cast off his pompousness and vanity, and was known to favor war to the bitter end. Dick and his squadron circled above the broken dome as the car that carried the Vice-president and the secretaries of State and for War approached along the Avenue.

Rat-tat, rat-a-tat-tat!

Out of the blue sky streams of lead were poured into the assembled multitudes. Instantly they had become converted into a panic-stricken mob, turning this way and that.

Rat-a-tat-tat. Swaths of dead and dying men rolled in the dust, and, as wheat falls under the reaper's blade, the mob melted away in lines and by battalions. Within thirty seconds the whole terrain was piled with dead and dying.

"My God, it's massacre! It's murder!" shouted Dick.

hey had not even waited for the twelve hours to expire. To and fro the invisible airplanes shot through the blue evening sky, till the last fugitives were streaming away in all directions like hunted deer, and the dead lay piled in ghastly heaps everywhere.

Out of these heaps wounded and dying men would stagger to their feet to shake their fists impotently at their murderers.

In vain Dick and his squadron strove to dash themselves into the invisible airships. The pilots eluded them with ease, sometimes sending a contemptuous round of machine-gun bullets in their direction, but not troubling to shoot them down.

Two small boys, carrying a huge banner with "No Surrender" across it, were walking off the ghastly field. Twelve or fourteen years old at most, they disdained to run. They were singing, singing the National Anthem, though their voices were inaudible through the turmoil.

Rat-tat! Rat-tat-a-tat! The fiends above loosed a storm of lead upon them. Both fell. One rose, still clutching the banner in his hand and waved it aloft. In a sudden silence his childish treble could be heard:

My country, 'tis of thee

Sweet land of lib-er-ty—

The guns rattled again. Clutching the blood-stained banner, he dropped across the body of his companion.

Suddenly a broad band of black soared upward from the earth. Those in charge of the cylinders placed about the Capitol had released the gas.

A band of darkness, rising into the blue, cutting off the earth, making the summit of the ruined Capitol a floating dome. But, fast as it rose, the invisible airships rose faster above it.

A last vicious volley! Two of Dick's flight crashing down upon the piles of dead men underneath! And nothing was visible, though the darkness rose till it obliterated the blue above.

t dawn the Council sat, after an all-night meeting. Vice-president Tomlinson, one arm shattered by a machine-gun bullet, still occupied the chair at the head of the table.

Outside, immediately about the White House, there was not a sound. Washington might have been a city of the dead. The railroad terminals, however, were occupied by a mob of people, busily looting. There was great disorder. Organized government had simply disappeared.

Each man was occupied only with obtaining as much food as he could carry, and taking his family into rural[48] districts where the Terror would not be likely to pursue. All the roads leading out of Washington—into Virginia, into Maryland, were congested with columns of fugitives that stretched for miles.

Some, who were fortunate enough to possess automobiles, and—what was rarer—a few gallons of gas, were trying to force their way through the masses ahead of them; here and there a family trudged beside a pack-horse, or a big dog drew an improvised sled on wheels, loaded with flour, bacon, blankets, pillows. Old men and young children trudged on uncomplaining.

The telegraph wires were still, for the most part, working. All the world knew what was happening. From all the big cities of the East a similar exodus was proceeding. There was little bitterness and little disorder.

It was not the airship raids from which these crowds were fleeing. Something grimmer was happening. The murderous attack upon the populace about the Capitol had been merely an incident. This later development was the fulfilment of the Invisible Emperor's ultimatum.

Death was afield, death, invisible, instantaneous, and inevitable. Death blown on the winds, in the form of the deadliest of unknown gases.

n the Blue Room of the White House a score of experts had gathered. Dick, too, with the chiefs of his staff, Stopford, and the army and naval heads. Among them was the chief of the Meteorological Bureau, and it was to him primarily that Tomlinson was reading a telegraphic dispatch from Wilmington, South Carolina:

"The Invisible Death has reached this point and is working havoc throughout the city, spreading from street to street. Men are dropping dead everywhere. A few have fled, but—"

The sudden ending of the dispatch was significant enough. Tomlinson picked up another dispatch from Columbia, in the same State:

"Invisible Death now circling city," he read. "Business section already invaded. All other telegraphists have left posts. Can't say how long—"

And this, too, ended in the same way. There were piles of such communications, and they had been coming in for eighteen hours. At that moment an orderly brought in a dozen more.

Tomlinson showed the head of the Meteorological Bureau the chart upon the table. "We've plotted out a map as the wires came in, Mr. Graves," he said. "The Invisible Death struck the southeast shore of the United States yesterday afternoon near Charleston. It has spread approximately at a steady rate. The wind velocity—?"

"Remains constant. Seventy miles an hour. Dying down a little," answered Graves.

"The death line now runs from Wilmington, South Carolina, straight to Augusta, Georgia," the Vice-president pursued. "Every living thing that this gas has encountered has been instantly destroyed. Men, cattle, birds, vermin, wild beasts. The gas is invisible and inodorous. These gentlemen believe it may be a form of hydrocyanic acid, but of a concentration beyond anything known to chemistry, so deadly that a billionth part of it to one of air must be fatal, otherwise it could not have traveled as it has done. Warnings have been broadcasted, but there are no stocks of chemicals that might counteract it. Flight is the only hope—flight at seventy miles an hour!"

is voice shook. "This gas has been loosed, as you told us, upon the wings of the hurricane that came through the Florida Strait. What are the chances of its reaching Washington?"

"Mr. Vice-president, if the wind continues, and this gas has sufficient concentration, it should be in Washington within the next eight hours." Graves replied. "If the wind changes direc[49]tion, however, this gas will probably be blown out to sea, or into the Alleghanies, where it will probably be dissipated among the hills, or by the foliage on the mountains. I'm not a chemist—"

"No, sir, and I am not consulting you as one," answered old Tomlinson. "A death belt several hundred miles in length and three or four hundred deep has already been cut across this continent. We are faced with wholesale, unmitigated murder, on such a scale as was never known before. But we are an integral part of America, and Washington has no more right to expect immunity than our devastated Southern States. The question we wish to put to you is, can you trace the exact course taken by the hurricane?"

"I can, Mr. Vice-president," answered Graves. "It originated somewhere in the West Indian seas, like all these storms. We've been getting our reports almost as usual. Our first one came from Nassau, which was badly damaged. The storm missed the Florida coast, as many of them do, and struck the coast of South Carolina—in fact, we received a report from Charleston, which must have almost coincided with your first report of the gas."

"If the storm missed the Florida coast, it follows that the gas was not discharged from any point on the American continent," said Tomlinson. "From some point off Florida—from some island, or from a plane or from a ship at sea."

"Not from a ship at sea, Mr. Vice-president," interposed the head of the Chemical Bureau. "To discharge gas on such an extensive scale would require more space than could be furnished by the largest vessel, in my opinion."

"In all probability the gas was 'loaded,' so to say, onto the gale somewhere in the Bahamas," said Graves. "That seems to me the most likely explanation."

ice-president Tomlinson nodded, and picked up one of the latest telegraphic dispatches, as if absently.

"Gentlemen," he said, "the Invisible Death has already reached Charlotte."

He picked up another. "Reported Abaco Island, Bahamas, totally wrecked by storm. All communication has ceased," he read. He turned to Dick and spoke as if inspired. "Captain Rennell, there

Comments (0)