The Wailing Asteroid, Murray Leinster [top fiction books of all time TXT] 📗

- Author: Murray Leinster

Book online «The Wailing Asteroid, Murray Leinster [top fiction books of all time TXT] 📗». Author Murray Leinster

After a time, Burke gave up trying to explain things. And when one and then another duplicate drive worked, the argument ceased. But eminent physicists still had a resentful feeling that Burke was cheating on them somehow.

Then for days nothing happened. One of the three men in the ship always stayed in the control-chair where he could check the ship's course against the homing signals from the asteroid. He might have to correct it by the fraction of a hair, or swing ship and put on more drive if the radar should show celestial debris in the spaceship's path. Every so many hours the ship had to be swung about so that instead of accelerating she decelerated, or instead of decelerating gained fresh speed. But that was all.

On the fifth day there was the flash of a meteor on the radar. On the seventh day an object which could have been the second or third unmanned Russian probe showed briefly at the very edge of the radar screens. In essence, however, the journey was pure tedium. Burke wearied of making sure that his work was good, though he congratulated himself that nothing did happen to break the monotony. Holmes admitted that he was disappointed. He'd wanted to make the journey because he'd sailed in everything but a spaceship. But there was no fun in it. Keller alone seemed comfortably absorbed. He prepared daily lists of instrument-readings to be sent back to Earth. They would be of enormous importance to science-minded people. They were not of interest to Sandy.

Even when she talked to Burke, it was necessarily impersonal. There could be no privacy which was not ostentatious. The two girls used the lower compartment, the three men the upper and larger one. For Sandy to talk privately with Burke, she'd have had to go to the small bottom section of the ship. Holmes and Pam faced the same situation. It was uncomfortable. So they developed a perfectly pleasant habit of talking exclusively of things everybody could talk about. It did not bother Keller, who would hardly average a dozen words in twenty-four hours, but Sandy muttered to herself when she and Pam retired for what was a ship-night's rest.

When they went past the orbit of Mars, agitated instructions came out from Earth. The asteroid belts began beyond Mars. Elaborate directions came. The ship was tracked by radar telescopes all around the world, direction-finding on its transmission. Croydon kept track. American radar bowls picked up the ship's voice. South American and Hawaiian and Japanese and Siberian radar telescopes determined the ship's position every time a set of code symbols reached Earth from the ship. Of course, there were also the beepings and the seventy-nine-minute-spaced identical broadcasts from farther out from the sun.

Somebody got a brilliant idea and authority to try it. An interview for broadcast on Earth was sought with somebody on the ship. It was then a hundred thirty million miles from Earth, and ninety-two million more from the sun. Largely out of boredom Sandy agreed to answer questions. But at the speed of light it required eleven minutes to reach her from Earth, and as long for her reply to be received. It did not make for liveliness, so she spoke curtly for five minutes and stopped. She talked at random about housekeeping in space. Without knowing it, she was praised for her domesticity in many pulpits the following Sunday, and eight hundred ninety-two proposals of marriage piled up in mail addressed to her in care of the United States government. Twelve were in Russian.

But nothing really exciting happened aboard the spaceship. It was Burke's guess that they could go directly through the asteroid belt along the plane of the ecliptic, and not get nearer than ten thousand miles to any bit of shattered stone or metal in orbit out there. He was almost right. There was only one occasion when his optimism came into doubt.

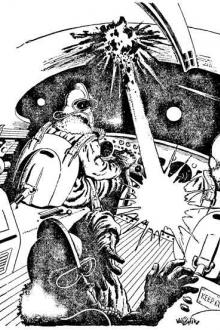

It was on the ninth day out from Earth. Experimentally, the ship coasted on attained momentum, using no drive. There was, then, no substitute for gravity and everyone and everything in the ship was weightless. The power obtainable from the sun as heat had dwindled to one-ninth of that at the Earth's distance. But what was received could be stored, and was. Meanwhile the ship plunged onward at very nearly four hundred miles per second. Burke, Keller, and Holmes together labored over a self-contained diving suit which they hoped could be used as a space suit in dire emergency and for brief periods. They wanted to get the feel of using it with internal pressure and weightlessness as conditions. Sandy sat at the transmitter, working at code which by now she heartily loathed. Pam sat in the control-chair, watching the instruments.

There was a buzz. Burke snapped his head around to see the radar screen. A line of light appeared on it. It aimed directly at the center of the screen, which meant that whatever had been picked up was on a collision course with the ship. Burke plunged toward the control-chair to take over. But he'd forgotten the condition of no-gravity. He went floating off in mid-air, far wide of the chair.

He barked orders to Pam, who was least qualified of anybody aboard to meet an emergency of this sort. She panicked. She did nothing. Holmes took precious seconds to drag himself to the controls by what hand-holds could be had. The glowing white line on the radar screen lengthened swiftly. It neared the center. It reached the center. Burke and Holmes froze.

There was a curious flashing change in a vision-screen. An image flashed into view. It was a jagged, tortured, irregularly-shaped mass of stone or metal, distorted in its representation by the speed at which it passed the television lens. It was perhaps a hundred yards in diameter. It could never have been seen from Earth. It might circle the sun in its lonely orbit for a hundred million years and never be seen again.

It went away to nothing. It had missed by yards or fathoms, and Burke found himself sweating profusely. Holmes was deathly white. Keller very carefully took a deep breath, swallowed, and went back to his work on the diving-suit-qua-space-suit. Sandy hadn't noticed anything at all. But Pam burst into abrupt, belated tears, and Holmes comforted her clumsily. She was bitterly ashamed that she'd done nothing to meet the emergency which came while she was at the control-board, and which was the only emergency they'd encountered since the ship's departure from Earth.

After that, they put on the drive and used reserve fuel. It was necessary to check their speed, anyhow. They were very near the source of the beeping signal they'd steered by for so long. The directional receiver pointed to it had long since been turned down to its lowest possible volume, and still the beepings were loud.

On the eleventh day after their take-off, they sighted Asteroid M-387. They had traveled two hundred seventy million miles at an averaged-out speed of very close to three hundred miles per second. Despite muting, the beepings from the loud-speakers were monstrous noises.

"Try a call, Holmes," said Burke. "But they ought to know we're here."

He felt strange. He'd brought the ship to a stop about four or five miles from M-387. The asteroid was a mass of dark stuff with white outcroppings at one place and another. The ship seemed to edge itself toward it. The floating mass of stone and metal had no particular shape. It was longer than it was wide, but its form fitted no description. A mountain which had been torn from solidity with its roots of stone attached might look like Schull's Object as it turned slowly against a background of myriads of unblinking stars.

There was no change in the beeping that came from the singular thing. It did rotate, but so slowly that one had to watch for long minutes to be sure of it. There was no outward sign of any reaction to the ship's presence. Holmes took the microphone.

"Hello! Hello!" he said absurdly. "We have come from Earth to find out what you want."

No answer. No change in the beeping calls. The asteroid turned with enormous deliberation.

Sandy said suddenly, "Look there! A stick! No, it's a mast! See, where the patch of white is?"

Burke very, very gingerly drew closer to the monstrous thing which hung in space. It was true. There was a mast of some sort sticking up out of white stone. The direction-indicators pointed to it. The beeping stopped and a broadcast began. It was the standard broadcast Earth heard every seventy-nine minutes.

There was no reply to Holmes' call. There was no indication that the ship's arrival had been noted. On Earth the ignoring of human broadcasts to M-387 had seemed arrogance, indifference, a superior and menacing contempt for man and all his works; somehow, here the effect was different. This irregular mass was a fragment of something that once had been much greater. It suddenly ceased to seem menacing because it seemed oblivious. It acted blindly, by rote, like some mechanism set to operate in a certain way and unable to act in any other.

It did not seem alive. It had signaled like a robot beacon. Now it felt like one. It was one.

"Look, coming around toward us," said Holmes very quietly. "There's something that looks like a tunnel. It's not a crevasse. It was cut."

Burke nodded.

"Yes," he said thoughtfully. "I think we'll explore it. But I don't really expect we'll find any life here. There's nothing outside to see but a single metal mast. We've got some signal lights on our hull. If we're careful—"

No one objected. The appearance of the asteroid was utterly disappointing. Its lifelessness and its obliviousness to their coming and their calls were worse than disappointing. There was nothing to be seen but a metal stick from which signals went out to nowhere.

Burke jockeyed the little ship to the tunnel-mouth. It was fully a hundred feet in diameter. He turned on the ship's signal lights. Gently, cautiously, he worked down the very center of the very large bore.

It was perfectly straight. They went in for what seemed an indefinite distance. Presently the signal lights showed that the wall was smoothed. The bore grew smaller still. They went on and on.

Suddenly Keller grunted. He pointed to one of the six television screens which aimed out the length of the tunnel and showed the stars beyond.

Those stars were being blotted out. Something vast moved slowly and deliberately across the shaft they navigated. It closed the opening. Their retreat was blocked. The ship was shut in, in the center of a mountain of stone which floated perpetually in emptiness. Burke checked the ship's forward motion, judging their speed by the side walls shown by the ship's outside lights.

Very, very slowly, faint illumination appeared outside. In seconds they could see that the light came from long tubes of faint bluish light. The light changed. It grew stronger. It turned green and then yellowish and then became very bright, indeed.

Then nothing more took place. Nothing whatever. The five inside the ship waited more than an hour for some other development, but absolutely nothing happened.

Chapter 6There was a tiny shock; in a minute, trivial contact of the ship with something outside it. Drifting within the now brightly lighted bore, it had touched the wall. There was no force to the impact.

Keller made an interested noise. When eyes turned to him, he pointed to a dial. A needle on that dial pointed just past

Comments (0)