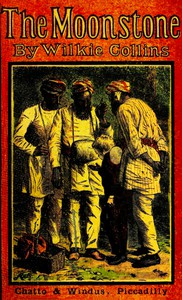

The Moonstone, Wilkie Collins [howl and other poems TXT] 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

Book online «The Moonstone, Wilkie Collins [howl and other poems TXT] 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

June the sixteenth brought an event which made Mr. Franklin’s chance look, to my mind, a worse chance than ever.

A strange gentleman, speaking English with a foreign accent, came that morning to the house, and asked to see Mr. Franklin Blake on business. The business could not possibly have been connected with the Diamond, for these two reasons—first, that Mr. Franklin told me nothing about it; secondly, that he communicated it (when the gentleman had gone, as I suppose) to my lady. She probably hinted something about it next to her daughter. At any rate, Miss Rachel was reported to have said some severe things to Mr. Franklin, at the piano that evening, about the people he had lived among, and the principles he had adopted in foreign parts. The next day, for the first time, nothing was done towards the decoration of the door. I suspect some imprudence of Mr. Franklin’s on the Continent—with a woman or a debt at the bottom of it—had followed him to England. But that is all guesswork. In this case, not only Mr. Franklin, but my lady too, for a wonder, left me in the dark.

On the seventeenth, to all appearance, the cloud passed away again. They returned to their decorating work on the door, and seemed to be as good friends as ever. If Penelope was to be believed, Mr. Franklin had seized the opportunity of the reconciliation to make an offer to Miss Rachel, and had neither been accepted nor refused. My girl was sure (from signs and tokens which I need not trouble you with) that her young mistress had fought Mr. Franklin off by declining to believe that he was in earnest, and had then secretly regretted treating him in that way afterwards. Though Penelope was admitted to more familiarity with her young mistress than maids generally are—for the two had been almost brought up together as children—still I knew Miss Rachel’s reserved character too well to believe that she would show her mind to anybody in this way. What my daughter told me, on the present occasion, was, as I suspected, more what she wished than what she really knew.

On the nineteenth another event happened. We had the doctor in the house professionally. He was summoned to prescribe for a person whom I have had occasion to present to you in these pages—our second housemaid, Rosanna Spearman.

This poor girl—who had puzzled me, as you know already, at the Shivering Sand—puzzled me more than once again, in the interval time of which I am now writing. Penelope’s notion that her fellow-servant was in love with Mr. Franklin (which my daughter, by my orders, kept strictly secret) seemed to be just as absurd as ever. But I must own that what I myself saw, and what my daughter saw also, of our second housemaid’s conduct, began to look mysterious, to say the least of it.

For example, the girl constantly put herself in Mr. Franklin’s way—very slyly and quietly, but she did it. He took about as much notice of her as he took of the cat; it never seemed to occur to him to waste a look on Rosanna’s plain face. The poor thing’s appetite, never much, fell away dreadfully; and her eyes in the morning showed plain signs of waking and crying at night. One day Penelope made an awkward discovery, which we hushed up on the spot. She caught Rosanna at Mr. Franklin’s dressing-table, secretly removing a rose which Miss Rachel had given him to wear in his button-hole, and putting another rose like it, of her own picking, in its place. She was, after that, once or twice impudent to me, when I gave her a well-meant general hint to be careful in her conduct; and, worse still, she was not over-respectful now, on the few occasions when Miss Rachel accidentally spoke to her.

My lady noticed the change, and asked me what I thought about it. I tried to screen the girl by answering that I thought she was out of health; and it ended in the doctor being sent for, as already mentioned, on the nineteenth. He said it was her nerves, and doubted if she was fit for service. My lady offered to remove her for change of air to one of our farms, inland. She begged and prayed, with the tears in her eyes, to be let to stop; and, in an evil hour, I advised my lady to try her for a little longer. As the event proved, and as you will soon see, this was the worst advice I could have given. If I could only have looked a little way into the future, I would have taken Rosanna Spearman out of the house, then and there, with my own hand.

On the twentieth, there came a note from Mr. Godfrey. He had arranged to stop at Frizinghall that night, having occasion to consult his father on business. On the afternoon of the next day, he and his two eldest sisters would ride over to us on horseback, in good time before dinner. An elegant little casket in china accompanied the note, presented to Miss Rachel, with her cousin’s love and best wishes. Mr. Franklin had only given her a plain locket not worth half the money. My daughter Penelope, nevertheless—such is the obstinacy of women—still backed him to win.

Thanks be to Heaven, we have arrived at the eve of the birthday at last! You will own, I think, that I have got you over the ground this time, without much loitering by the way. Cheer up! I’ll ease you with another new chapter here—and, what is more, that chapter shall take you straight into the thick of the story.

June twenty-first, the day of the birthday, was cloudy and unsettled at sunrise, but towards noon it cleared up bravely.

We, in the servants’ hall, began this happy anniversary, as usual, by offering our little presents to Miss Rachel, with the regular speech delivered annually by me as the chief. I follow the plan adopted by the Queen in opening Parliament—namely, the plan of saying much the same thing regularly every year. Before it is delivered, my speech (like the Queen’s) is looked for as eagerly as if nothing of the kind had ever been heard before. When it is delivered, and turns out not to be the novelty anticipated, though they grumble a little, they look forward hopefully to something newer next year. An easy people to govern, in the Parliament and in the Kitchen—that’s the moral of it.

After breakfast, Mr. Franklin and I had a private conference on the subject of the Moonstone—the time having now come for removing it from the bank at Frizinghall, and placing it in Miss Rachel’s own hands.

Whether he had been trying to make love to his cousin again, and had got a rebuff—or whether his broken rest, night after night, was aggravating the queer contradictions and uncertainties in his character—I don’t know. But certain it is, that Mr. Franklin failed to show himself at his best on the morning of the birthday. He was in twenty different minds about the Diamond in as many minutes. For my part, I stuck fast by the plain facts as we knew them. Nothing had happened to justify us in alarming my lady on the subject of the jewel; and nothing could alter the legal obligation that now lay on Mr. Franklin to put it in his cousin’s possession. That was my view of the matter; and, twist and turn it as he might, he was forced in the end to make it his view too. We arranged that he was to ride over, after lunch, to Frizinghall, and bring the Diamond back, with Mr. Godfrey and the two young ladies, in all probability, to keep him company on the way home again.

This settled, our young gentleman went back to Miss Rachel.

They consumed the whole morning, and part of the afternoon, in the everlasting business of decorating the door, Penelope standing by to mix the colours, as directed; and my lady, as luncheon time drew near, going in and out of the room, with her handkerchief to her nose (for they used a deal of Mr. Franklin’s vehicle that day), and trying vainly to get the two artists away from their work. It was three o’clock before they took off their aprons, and released Penelope (much the worse for the vehicle), and cleaned themselves of their mess. But they had done what they wanted—they had finished the door on the birthday, and proud enough they were of it. The griffins, cupids, and so on, were, I must own, most beautiful to behold; though so many in number, so entangled in flowers and devices, and so topsy-turvy in their actions and attitudes, that you felt them unpleasantly in your head for hours after you had done with the pleasure of looking at them. If I add that Penelope ended her part of the morning’s work by being sick in the back-kitchen, it is in no unfriendly spirit towards the vehicle. No! no! It left off stinking when it dried; and if Art requires these sort of sacrifices—though the girl is my own daughter—I say, let Art have them!

Mr. Franklin snatched a morsel from the luncheon-table, and rode off to Frizinghall—to escort his cousins, as he told my lady. To fetch the Moonstone, as was privately known to himself and to me.

This being one of the high festivals on which I took my place at the side-board, in command of the attendance at table, I had plenty to occupy my mind while Mr. Franklin was away. Having seen to the wine, and reviewed my men and women who were to wait at dinner, I retired to collect myself before the company came. A whiff of—you know what, and a turn at a certain book which I have had occasion to mention in these pages, composed me, body and mind. I was aroused from what I am inclined to think must have been, not a nap, but a reverie, by the clatter of horses’ hoofs outside; and, going to the door, received a cavalcade comprising Mr. Franklin and his three cousins, escorted by one of old Mr. Ablewhite’s grooms.

Mr. Godfrey struck me, strangely enough, as being like Mr. Franklin in this respect—that he did not seem to be in his customary spirits. He kindly shook hands with me as usual, and was most politely glad to see his old friend Betteredge wearing so well. But there was a sort of cloud over him, which I couldn’t at all account for; and when I asked how he had found his father in health, he answered rather shortly, “Much as usual.” However, the two Miss Ablewhites were cheerful enough for twenty, which more than restored the balance. They were nearly as big as their brother; spanking, yellow-haired, rosy lasses, overflowing with super-abundant flesh and blood; bursting from head to foot with health and spirits. The legs of the poor horses trembled with carrying them; and when they jumped from their saddles (without waiting to be helped), I declare they bounced on the ground as if they were made of india-rubber. Everything the Miss Ablewhites said began with a large O; everything they did was done with a bang; and they giggled and screamed, in season and out of season, on the smallest provocation. Bouncers—that’s what I call them.

Under cover of the noise made by the young ladies, I had an opportunity of saying a private word to Mr. Franklin in the hall.

“Have you got the Diamond safe, sir?”

He nodded, and tapped the breast-pocket of his coat.

“Have you seen anything of the Indians?”

“Not a glimpse.” With that answer, he asked for my lady, and, hearing she was in the small drawing-room, went there straight. The bell rang, before he had been a minute in the room, and Penelope was sent to tell Miss Rachel that Mr. Franklin Blake wanted to speak to her.

Crossing the hall, about half an hour afterwards, I was brought to a sudden standstill by an outbreak of screams from the small drawing-room. I can’t say I was at all alarmed; for I recognised in the screams the favourite

Comments (0)