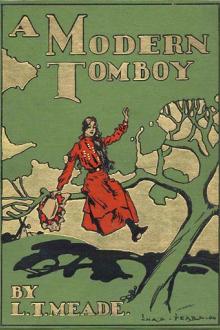

A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls, L. T. Meade [ready to read books .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

Book online «A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls, L. T. Meade [ready to read books .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

"Now, Cartery dear," she said, "you talk to Rosamund Cunliffe, who is a friend of mine, and I will go and have a good, romping game of tennis. Oh, I see they are just breaking up the present set, so I am just in time."

Off ran Maud. Miss Carter's light-blue eyes followed her with an expression of the deepest affection.

"You seem very fond of her," said Rosamund suddenly.

"I don't know what I should have done without her. She saved my life and my reason."

"I don't want to talk about what has evidently given you very great distress," said Rosamund after a time; "but I should like to tell you that I know."

"You know?" said Miss Carter, beginning to tremble, and turning very pale.

"Yes, for Irene told me."

"My dear, dear Miss Cunliffe, how had you the courage to go with her in that terrible boat? She actually took you into the current—that appalling current where one is so powerless—and you escaped!"

"Oh, yes," said Rosamund lightly. "It was a mere nothing. You see, I am stronger than she is. All she wants is management."

"I could never manage her," said Miss Carter. "I could tell you of other things she did."

"No, I don't want to hear unless you are going to tell me something nice about her. Every one seems to speak against that poor girl; but I am determined to be her friend."

"Are you really?" said Miss Carter, suddenly changing her tone and looking fixedly at Rosamund. "Then you must be about the noblest girl in the world."

These words were very gratifying to Rosamund, who did think herself rather good in taking up Irene's cause; although, of course, she was fascinated by the exceedingly naughty young person.

"Yes, indeed, you are splendid," said Miss Carter; "and I know there must be good in the child. Such courage, such animal spirits, such daring cannot be meant for nothing. The fact is, her mother cannot manage her. Her mother is too gentle, too like me."

"Dear Lady Jane! Miss Carter, when my mother was young she was her great friend, and she said that Lady Jane was rather naughty."

"Ah!" said Miss Carter, with a sigh, "she has left all that behind her a long time ago. The only time I found her hard and unsympathetic was when I told her that I could not stay any longer at The Follies. She begged and implored of me to stay; but, of course, you know the story. I was under a promise to go, and I could not let out that Irene had wrung it from me at the risk of my life. So I went, and she took no notice of me, although it seemed to me that a sort of despair filled her face. Anyhow, off I went, and I am a happy woman here. I don't know what is to be done with Irene."

How long were you with her?

"A month altogether; but that month seems like years. I was very glad to get the post, for I must tell you, Miss Cunliffe, that I am poor and dependent altogether on what I earn for my daily bread. I have an old mother at home; I help her to keep alive with some of my earnings; and Lady Jane offered a very big salary—over a hundred a year—and there was only one child to teach, and I thought it would be so delightful. She mentioned the charms of the country-house, and that she did not require a great deal of education; and she even spoke of the lake and the boat. Oh, I was so glad to come! for I am not certificated, you know, and cannot get the posts that other women can. Well, anyhow, I arrived, and for a month it was really a reign of terror."

Miss Carter began to tremble.

"You must not do that, really," said Rosamund. "You are not suited to it. But do tell me what you think a very strong-minded person would have made of Irene."

"Well, you see, the first and principal thing was not to fear her, and it was impossible not to fear her, for she was up to so many tricks; she was worse than the most mischievous school-boy who ever walked. She would suddenly come into the drawing-room in her gymnasium clothes, and turn somersaults up and down the room in the presence of Lady Jane's distinguished guests. Oh! I cannot tell you half she did—I dare not tell you. There was no trick she was not up to; but you will know for yourself if you really mean to have more to do with her."

"I certainly mean to have a great deal more to do with her, although at the present moment I am forbidden by Professor Merriman even to speak to her."

"I know the Merrimans have a very bad opinion of her," said Miss Carter.

"Yes, that is just it; but she is the daughter of my mother's dearest friend, and I am not going to give her up."

"Yet you are at school at Mr. Merriman's!"

"That is true."

Miss Carter looked in a puzzled way at Rosamund.

"I cannot reveal any more of my plans," said Rosamund, speaking in a rather lofty tone; "but now I want to know a few things about her. Is she stingy or generous?"

"Oh! absolutely and perfectly generous, and in her own way forgiving too; and I do not think she could tell a lie, for she has no fear in her, and I suppose it is fear that makes us tell lies. She has never feared any mortal. She has no respect for authority, not even her mother; and although she rushes at her sometimes and smothers her with kisses, she seems to have no real affection for her. If I could be sure that she was absolutely affectionate I think something could be done for her. Now, that is all I can tell you. You can scarcely believe how this subject distresses me and causes that terrible trembling to come on. I don't think, Miss Cunliffe, young as you are, and brave as you doubtless are, you ought to undertake the reform of that wild girl at your age. Allow me to say that you are sent to school by your parents for a definite purpose, and not to undertake the reform of Irene Ashleigh."

A frown came over Rosamund's face, and Miss Carter, glancing at her, saw that her words had caused displeasure.

"Forgive me," she said gently; "I don't really mean to be unkind. Indeed, I admire you, and admire your bravery beyond words. To be as brave as you are would be a noble gift, and if it were only my own heritage, how happy I should be!"

"I tell you what it is, Miss Carter," said Rosamund suddenly; "if ever I want your help, and if I can assure you that you can give it without personal danger to yourself, will you give it to me?"

"If I think it right I will truly do so."

"Then the day may come," said Rosamund; "there is no saying."

Just then Ivy's pretty voice was heard calling Miss Carter.

"She is my second youngest pupil, and such a darling child!" said Miss Carter, her eyes brightening. "Yes, dear," she continued as Ivy danced up to her; "what is it?"

"We want a game of Puss-in-the-corner, and the silliest and youngest among us are going to play."

Jumping up as she spoke, Miss Carter said she belonged to that group, and Rosamund turned somewhat disdainfully away.

CHAPTER IX. AN UNEXPECTED ROOM-MATE.It was on that very same day that Jane Denton, Rosamund's special friend, complained of sudden chill and headache. She was a little sick, too, and could not touch her supper. Mrs. Merriman always kept a clinical thermometer handy, and on discovering that the young girl's temperature was considerably over one hundred degrees, she took fright and had her removed to a room in a distant part of the house.

"If she is not better in the morning we will send for the doctor," was her verdict. "Now, girls, one thing: I do not wish the Professor to be annoyed. I undertook this school in order to save him anxiety, and if he knows of every trifling indisposition he may be terribly vexed and put out. I therefore take charge of Jane to-night, sleeping in her room and looking after her, and administering to her simple remedies. If in the morning she is no better I will send for the doctor, and then we will know how to act. Meanwhile you, Rosamund, have your room to yourself."

Rosamund was distressed for her friend, and boldly announced at once that she would act as nurse.

"I ought to," she said. "She is my friend, and I have always been fond of her. Besides, it seems exceedingly hard that you, Mrs. Merriman, who work so much for us all day long, should have to work at night as well. Do let me undertake this."

Mrs. Merriman could scarcely keep the tears back from her eyes when Rosamund spoke. She could not help liking the girl, notwithstanding her eccentricities and her very bold act of disobedience on the previous Sunday. But she was firm in her resolve.

"No, dear," she said; "I am obliged to you for making the offer."

"Hypocrite!" said Lucy angrily to herself. "She knows it cannot be accepted."

Mrs. Merriman was not looking at Lucy; on the contrary, she was looking full into Rosamund's face.

"I am obliged to you for making the offer," she continued; "but it is impossible for me to accept it, for the simple reason that there is just the possibility that Jane may be going to have some infectious disease, in which case I could not hear of any other girl in my establishment running any risk. Therefore you see for yourself that I cannot accept your offer. I should be unfaithful to your mother if I did."

"Oh, come, Rosamund!" said Laura Everett; "do let us go out and have a chat together. Of course, Mrs. Merriman is right. We will help you all we can, Mrs. Merriman, by being extra good girls. Isn't that the best way?"

Mrs. Merriman admitted that it was, and the two girls, their arms entwined, went out into the soft summer night. Laura Everett, with her merry face, blue eyes, and fair hair, was a great contrast to Rosamund Cunliffe. She was exceedingly clever and fond of books. Most of her tastes lay, however, in a scientific direction. She was devoted to chemistry and mathematics, and could already work well in these two branches of science. She was intensely matter-of-fact, and in reality had nothing whatever in common with Rosamund.

Lucy Merriman had a great admiration for Laura Everett: in the first place, because her mother, Lady Everett, was Mrs. Merriman's old friend; and in the next place, because she possessed, as Lucy expressed it, the invaluable gift of common-sense. She had rather taken Laura under her own wing, had intended to make her her special friend, had meant to trot her round and to show her to other friends; in short, as much as possible to divide her from Rosamund, whom she considered a most dangerous and pernicious influence.

But Laura had character of her own, and admired Rosamund; and now that she saw the girl looking rather pale, with an almost pathetic expression in her brown eyes, her heart smote her with a sense of pity, and she went up to her eagerly.

"I want you to tell me just what you think about the Singletons," she said. "Let us walk about under the trees. Isn't it nice and home-like here? Don't you think so, Rosamund?"

"Perhaps," said Rosamund in a dubious voice. Then she added impulsively, "You see, Laura, it is somewhat difficult for me to talk to you, for Lucy is your friend and she is not mine."

"I know you do not like her—I mean I know she is in every way your opposite; but if you only would take no notice of her little peculiarities, and accept her as she really is, you would soon find good points in her. She is devoted to her parents, and is very true. I know, of course, she is a little matter-of-fact."

"Yes, that is it," said Rosamund. "For goodness' sake, Laura, don't waste time talking about her. We can say as much as ever we like about the Singletons. I must say I am rather charmed with them."

"And so am I," said Laura, "particularly with Maud. She is so bright and unselfish."

"The person I like best of the entire group is Miss Carter," said Rosamund stoutly.

"What!" exclaimed Laura, with a laugh. "That poor, thin, frightened-looking governess—'Cartery love,' as they call her?"

"Yes, 'Cartery love,' or anything else you

Comments (0)