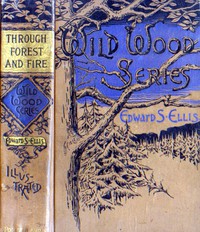

Through Forest and Fire<br />Wild-Woods Series No. 1, Edward Sylvester Ellis [smart books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis

Book online «Through Forest and Fire<br />Wild-Woods Series No. 1, Edward Sylvester Ellis [smart books to read .txt] 📗». Author Edward Sylvester Ellis

One of the lessons Sam had learned from his father was to reload his gun immediately after firing it, so as to be ready for any emergency. Accordingly, before stirring from his place, he threw out the shell from his breech-loader and replaced it with a new cartridge.

Just as he did so, he heard the report of a gun only a short distance to the left, at a point where Herbert Watrous should have been.

"He's scared up something," was the natural conclusion of Sam, who smiled as he added; "I wonder whether he could hit a bear a dozen feet off with that wonderful Remington of his. It's a good weapon, and I wish I owned one; but I wouldn't start out to hunt big game until I learned something about it."

The boy waited a minute, listening for some signal from his companion, but none was heard and he moved on again.

Sam, like many an amateur hunter, began to appreciate the value of a trained hunting dog. Bowser was not a pure-blooded hound; he was fat and he was faultily trained. He had stumbled upon the trail of the buck by accident and had plunged ahead in pursuit, until "pumped," when he seemed to lose all interest in the sport.

He now stayed close to Sam, continually looking up in his face as if to ask him when he was going to stop the nonsense and go back home.

He scarcely pricked his ears when the quail ran ahead of him, and paid no attention to the whirring made by the other. He had had all he wanted of that kind of amusement and showed no disposition to tire himself any further.

CHAPTER XIX. AN UNEXPECTED LESSON.As it was the height of the hunting season, the reports of guns were heard at varying distances through the woods, so that Sam could only judge when they were fired by his friends from their nearness to him.

He was well satisfied that the last shot was from the Remington of Herbert, while the one that preceded it a few minutes, he was convinced came from the muzzle-loader of Nick Ribsam, owned by Mr. Marston.

"The boys seem to have found something too do, but I don't believe they have seen anything of the bear—hallo!"

His last exclamation was caused by his unexpected arrival at a clearing, in the center of which stood a log cabin, while the half acre surrounding it showed that it had been cultivated during the season to the highest extent.

There was that air of thrift and cleanliness about the place which told the lad that whoever lived within was industrious, frugal, and neat.

"That's a queer place to build a house," said Sam, as he surveyed the scene; "no one can earn a living there, and it must make a long walk to reach the neighborhood where work is to be had."

Prompted by a natural curiosity, Sam walked over the faintly marked path until he stepped upon the piece of hewed log, which answered for a porch, directly in front of the door.

Although the latch string hung invitingly out, he did not pull it, but knocked rather gently.

"Come in!" was called out in a female voice, and the boy immediately opened the door.

A pleasing, neatly-clad young woman was working with her dishes at a table, while a fat chub of a boy, about two years old, was playing on the floor with a couple of kittens.

The mother, as she evidently was, turned her head so as to face the visitor, nodded cheerily, bade him good afternoon, and told him to help himself to one of the chairs, whose bottoms were made of white mountain ash, as fine and pliable as silken ribbons.

Sam was naturally courteous, and, thanking the lady for her invitation, he sat down, placing his cap on his knee. He said he was out on a hunt with some friends, and coming upon the cabin thought he would make a call, and learn whether he could be of any service to the lady and her child.

The mother thanked him, and said that fortunately she was not in need of any help, as her husband was well and able to provide her with all she needed.

Without giving the conversation in detail, it may be said that Sam Harper learned a lesson, during his brief stay in that humble cabin, which will go with him through life: it was a lesson of cheerfulness and contentment, to which he often refers, and which makes him thankful that he was led to turn aside from his sport even for a short while.

The husband of the woman worked for a farmer who lived fully four miles away, on the northern edge of the woods, and who paid only scant wages. The employee walked the four miles out so as to reach the farm by seven o'clock in the morning, and he did not leave until six in the evening. He did this summer and winter, through storm and sunshine, and was happy.

He lived in the lonely log cabin, because his employer owned it and gave him the rent free. It had been erected by some wood-choppers several years before, and was left by them when through with their contract, so that it was nothing to any one who did not occupy it.

The young man, although now the embodiment of rugged health and strength, had lain on a bed of sickness for six months, during which he hovered between life and death. His wife never left his side during that time for more than a few minutes, and the physician was scarcely less faithful. At last the wasting fever vanished, and the husband and father came back to health and strength again.

But he was in debt to the extent of $200, and he and his wife determined on the most rigid economy until the last penny should be paid.

"If Fred keeps his health," said the cheery woman, "we shall be out of debt at the end of two years more. Won't you bring your friends and stay with us to-night?"

This invitation was given with great cordiality, and Sam would have been glad to accept it, but he declined, through consideration for the brave couple, who would certainly be put to inconvenience by entertaining three visitors.

Sam thanked her for her kindness, and, rising to go, drew back the door and remarked:

"I notice you have a good rifle over the mantle; I don't see how your husband can get much time to use it."

"He doesn't; it is I who shoot the game, which saves half the cost of food; but," added the plucky little woman, "there is one game which I am very anxious to bring down."

"What is that?"

"A bear."

"Do you know whether there are any in the woods?"

"There is one, and I think more. My husband has seen it twice, and he took the gun with him when going to work, in the hope of gaining a chance to shoot it; but, when I caught sight of it on the edge of the clearing, he thought it best to leave the rifle for me to use."

"Why are you so anxious to shoot the bear?" asked Sam.

"Well, it isn't a very pleasant neighbor, and I have to keep little Tommy in the house all the time for fear the brute will seize him. Then, beside that, the bear has carried off some of Mr. Bailey's (that's the man my husband works for) pigs, and has so frightened his family that Mr. Bailey said he would give us twenty dollars for the hide of every bear we brought him."

"I hope it may be your fortune to shoot all in the woods," said Sam, as he bade her good-day again, and passed out and across the clearing into the forest.

"That's about the bravest woman I ever saw," said the lad to himself, as he moved thoughtfully in the direction of the limestone-rock, where it was agreed the three should meet to spend the night; "she ought to win, and if this crowd of bear hunters succeed in bagging the old fellow we will present him to her."

The thought was a pleasing one to Sam, who walked a short way farther, when he added, with a grim smile, "But I don't think that bear will lose any night's sleep on account of being disturbed by this crowd."

CHAPTER XX. BOWSER PROVES HIMSELF OF SOME USE.Sam Harper saw, from the position of the sun in the heavens, that he had stayed longer than he intended to in the cabin, and the short afternoon was drawing to a close.

He therefore moved at a brisk walk for a quarter of a mile, Bowser trotting at his heels as though he thought such a laborious gait uncalled for; but, as the lad then observed that the large limestone was not far away, he slackened his pace, and sat down on a fallen tree to rest.

"This is a queer sort of a hunt," he said to himself, "and I don't see what chance there is of any one of us three doing anything at all. Bowser isn't worth a copper to hunt with; all there was in him expended itself when he chased the buck and let it get away from him—hallo, Bowser, what's the matter with you?"

The hound just then began acting as though he felt the slighting remarks of his master, and meant to make him sorry therefor.

He uttered several sharp yelps and began circling around the fallen tree on which Sam was sitting. He went with what might be called a nervous gallop, frequently turning about and circumnavigating the lad and the log in the opposite direction.

All the time he kept up his barking and demonstrations, now and then running up to Sam, galloping several paces away, and then looking toward him and barking again with great vigor.

Sam watched his antics with amusement and interest.

"He acts as though he wanted me to follow him from this spot, though I cannot understand why he wants me to do that, since he is so lazy he would be glad to lie down and stay here till morning."

Studying the maneuvers of the hound, Sam became satisfied that the brute was seeking to draw him away from the fallen tree on which he was sitting.

The dog became more excited every minute. He trotted back and forth, running up to his young master and then darting off again, looking appealingly toward Sam, who finally saw that his actions meant something serious.

"I don't know why he wishes me to leave, but he has some reason for it, and I will try to find out."

Sam slowly rose from the fallen oak tree on which he was sitting, and as he did so his cap fairly lifted from his head with terror.

He caught the glint and scintillation in the sunlight of something on the ground on the other side of the trunk, and separated from him only by the breadth thereof, at the same instant that his ear detected the whirring rattle which told the fact that an immense rattlesnake had coiled itself therefor, and had just given its warning signal that it meant to strike.

Sam Harper never made such a quick leap in all his life as he did, when he bounded several feet from the log, with a yell as if the ground beneath him had become suddenly red-hot.

There is nothing on the broad earth which is held in such universal abhorrence as a snake, the sight of which sends a shiver of disgust and dread over nearly every one that looks upon it.

When Sam sat down on the fallen tree, he was probably almost near enough for the coiled crotalus to bury its fangs in him. It reared its head, and, without uttering its customary warning, most likely measured the intervening space with the purpose of striking.

The instinct of Bowser at this juncture told him of the peril of his master, and he began his demonstrations, intended to draw him away from the spot. At the same time, his barking, and trotting back and forth, diverted the attention of the rattlesnake to the hound, and thereby prevented him striking the unsuspicious boy.

It must have been, also, that during these few minutes the serpent vibrated his tail more than once, for the nature of the reptile leads him to do so; but the sound could not have been very loud, as it

Comments (0)