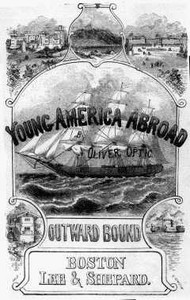

Outward Bound Or, Young America Afloat: A Story of Travel and Adventure, Optic [best non fiction books of all time txt] 📗

- Author: Optic

Book online «Outward Bound Or, Young America Afloat: A Story of Travel and Adventure, Optic [best non fiction books of all time txt] 📗». Author Optic

The capstan was manned, and the cable hove up to a short stay. The topsails and top-gallant sails were set; then the anchor was hauled up to the hawse-hole, catted and fished. The Young America moved; she wore round, and her long voyage was commenced. The courses and the royals were set, and she moved majestically down the bay. The steamer kept close by her, and salutations by shouts, cheers, and the waving of handkerchiefs, were continually interchanged, till the ship was several miles outside of the lower light.

The steamer whistled several times, to indicate that she was about to return. All hands were then ordered into the rigging of the ship; and cheer after cheer was given by the boys, and acknowledged by cheers on the part of the gentlemen, and the waving of handkerchiefs by the ladies. The steamer came about; the {126} moment of parting had come, and she was headed towards the city. Some of the students wept then; for, whatever charms there were in the voyage before them, the ties of home and friends were still strong. As long as the steamer could be seen, signals continued to pass between her and the ship.

"Captain Gordon, has the first master given the quartermaster the course yet?" asked Mr. Lowington, when the steamer had disappeared among the islands of the bay.

"No, sir; but Mr. Fluxion told him to make it east-north-east."

"Very well; but the masters should do this duty," added Mr. Lowington, as he directed the instructor in mathematics to require the masters, to whom belonged the navigation of the ship, to indicate the course.

William Foster was called, and sent into the after cabin with his associates, to obtain the necessary sailing directions. The masters had been furnished with a supply of charts, which they had studied daily, as they were instructed in the theory of laying down the ship's course. Foster unrolled the large chart of the North Atlantic Ocean upon the dinner table, and with parallel ruler, pencil, and compasses, proceeded to perform his duty.

"We want to go just south of Cape Sable," said he, placing his pencil point on that part of the chart.

"How far south of it?" asked Harry Martyn.

"Say twenty nautical miles."

The first master dotted the point twenty miles south of Cape Sable, which is the southern point of Nova Scotia, and also the ship's position, with his pencil. {127} He then placed one edge of the parallel ruler on both of these points, thus connecting them with a straight line.

A parallel ruler consists of two smaller rulers, each an inch in width and a foot in length, connected together by two flat pieces of brass, riveted into each ruler, acting as a kind of hinge. The parts, when separated, are always parallel to each other.

Foster placed the edge of the ruler on the two points made with the pencil, one indicating the ship's present position, the other the position she was to obtain after sailing two or three days. Putting the fingers of his left hand on the brass knob of the ruler, by which the parts are moved, he pressed down and held its upper half, joining the two points, firmly in its place. With the fingers of the right hand he moved the lower half down, which, in its turn, he kept firmly in place, while he slipped the upper half over the paper, thus preserving the direction between the points. By this process the parallel ruler could be moved all over the chart without losing the course from one point to the other.

On every chart there are one or more diagrams of the compass, with lines diverging from a centre, representing all the points. The parallel ruler is worked over the chart to one of these diagrams, where the direction to which it has been set nearly or exactly coincides with one of the lines representing a point of the compass.

The first master of the Young America worked the ruler down to a diagram, and found that it coincided {128} with the line indicating east by north; or one point north of east.

"That's the course," said Thomas Ellis, the third master—"east by north."

"I think not," added Foster. "If we steer that course, we should go forty or fifty miles south of Cape Sable, and thus run much farther than we need. What is the variation?"

"About twelve degrees west," replied Martyn.

The compass does not indicate the true north in all parts of the earth, the needle varying in the North Atlantic Ocean from thirty degrees east to nearly thirty degrees west. There is an imaginary line, extending in a north-westerly direction, through a point in the vicinity of Cape Lookout, called the magnetic meridian, on which there is no variation. East of this line the needle varies to the westward; and west of the line, to the eastward. These variations of the compass are marked on the chart, in different latitudes and longitudes, though they need to be occasionally corrected by observations, for they change slightly from year to year.

"Variation of twelve degrees," 1 repeated Foster, verifying the statement by an examination of the chart. That is equal to about one point, which, carried to the westward from east by north, will give the course east-north-east.

The process was repeated, and the same result being obtained, the first master reported the course to {129} Mr. Fluxion, who had made the calculation himself, in the professors' cabin.

"Quartermaster, make the course east-north-east," said the first master, when his work had been duly approved by the instructor.

"East-north-east, sir!" replied the quartermaster, who was conning the wheel—that is, he was watching the compass, and seeing that the two wheelmen kept the ship on her course.

There were two other compasses on deck, one on the quarter-deck, and another forward of the mainmast which the officers on duty were required frequently to consult, in order that any negligence in one place might be discovered in another. The after cabin and the professors' cabin were also provided with "tell-tales," which are inverted compasses, suspended under the skylights, by which the officers and instructors below could observe the ship's course.

The log indicated that the ship was making six knots an hour, the rate being ascertained every two hours, and entered on the log-slate, to be used in making up the "dead reckoning." The Young America had taken her "departure," that is, left the last land to be seen, at half past three o'clock. At four, when the log was heaved, she had made three miles; at six, fifteen miles; at eight, the wind diminishing and the log indicating but four knots, only eight miles were to be added for the two hours' run, making twenty-three miles in all. The first sea day would end at twelve o'clock on the morrow, when the log-slate would indicate the total of nautical miles the ship had run after taking her departure. This is {130} called her dead reckoning, which may be measured off on the chart, and should carry the vessel to the point indicated by the observations for latitude and longitude.

The wind was very light, and studding-sails were set alow and aloft. The ship only made her six knots as she pitched gently in the long swell of the ocean. The boys were still nominally under the order of "all hands on deck," but there was nothing for them to do, with the exception of the wheelmen, and they were gazing at the receding land behind them. They were taking their last view of the shores of their native land. Doubtless some of them were inclined to be sentimental, but most of them were thinking of the pleasant sights they were to see, and the exciting scenes in which they were to engage on the other side of the rolling ocean, and were as jolly as though earth had no sorrows for them.

The principal and the professors were pacing the quarter-deck, and doubtless some of them were wondering whether boys like the crew of the Young America could be induced to study and recite their lessons amid the excitement of crossing the Atlantic, and the din of the great commercial cities of the old world. The teachers were energetic men, and they were hopeful, at least, especially as study and discipline were the principal elements of the voyage, and each pupil's privileges were to depend upon his diligence and his good behavior. It would be almost impossible for a boy who wanted to go to Paris while the ship was lying at Havre, so far to neglect his duties as to forfeit the privilege of going. As these {131} gentlemen have not been formally introduced, the "faculty" of the ship is here presented:—

Robert Lowington, Principal.

Rev. Thomas Agneau, Chaplain.

Dr. Edward B. Winstock, Surgeon.

INSTRUCTORS.

John Paradyme, A.M., Greek and Latin.

Richard Modelle, Reading and Grammar.

Charles C. Mapps, A.M., Geography and History.

James E. Fluxion, Mathematics.

Abraham Carboy, M.D., Chemistry and Nat. Phil.

Adolph Badois, French and German.

These gentlemen were all highly accomplished teachers in their several departments, as the progress of the students during the preceding year fully proved. They were interested in their work, and in sympathy with the boys, as well as with the principal.

It was a very quiet time on board, and the crew were collected in little groups, generally talking of the sights they were to see. In the waist were Shuffles, Monroe, and Wilton, all feuds among them having been healed. They appeared to be the best of friends, and it looked ominous for the discipline of the ship to see them reunited. Shuffles was powerful for good or evil, as he chose, and Mr. Lowington regretted that he had fallen from his high position, fearing that the self-respect which had sustained him as an officer would desert him as a seaman, and permit him to fall into excesses.

Shuffles was more dissatisfied and discontented than {132} he had ever been before. He had desired to make the tour of Europe with his father, and he was sorely disappointed when denied this privilege; for with the family he would be free from restraint, and free from hard study. When he lost his rank as an officer, he became desperate and reckless. To live in the steerage and do seaman's duty for three months, after he had enjoyed the luxuries of authority, and of a state-room in the after cabin, were intolerable. After the cabin offices had been distributed, he told Monroe that he intended to run away that night; but he had found no opportunity to do so; and it was unfortunate for his shipmates that he did not.

"This isn't bad—is it, Shuffles?" said Wilton, as the ship slowly ploughed her way through the billows.

"I think it is. I had made up my mouth to cross the ocean in a steamer, and live high in London and Paris," replied Shuffles. "I don't relish this thing, now."

"Why not?" asked Wilton.

"I don't feel at home here."

"I do."

"Because you never were anywhere else. I ought to be captain of this ship."

"Well, you can be, if you have a mind to work for it," added Monroe.

"Work for it! That's played out. I must stay in the steerage three months, at any rate; and that while the burden of the fun is going on. If we were going to lie in harbor, or cruise along the coast, I would go in for my old place."

"But Carnes is out of the way now, and your {133} chance is better this year than it was last," suggested Monroe.

"I know that, but I can't think of straining every nerve for three months, two of them while we are going from port to port in Europe. When we go ashore at Queenstown, I shall have to wear a short jacket, instead of the frock coat of an officer; and I think the jacket would look better on some younger fellow."

"What are you going to do, Shuffles?" asked Wilton.

"I'd rather be a king among hogs, than a hog among kings."

"What do you mean by that?"

"No matter; there's time enough to talk over these things."

"Do you mean a mutiny?" laughed Wilton.

"Haven't you forgotten that?"

"No."

"I wonder what Lowington would say, if he knew I had proposed such a thing," added Shuffles, thoughtfully.

"He did know it, at the time you captured the runaways, for I told him."

"Did you?" demanded Shuffles, his brow contracting with anger.

"I told you I would tell him, and I did," answered Wilton. "You were a traitor to our fellows, and got us into a scrape."

"I was an officer then."

"No matter for that. Do you suppose, if I were an {134} officer, I would throw myself in your way when you were up to anything?"

"I don't know whether you would or not; but I wouldn't blow on you, if

Comments (0)