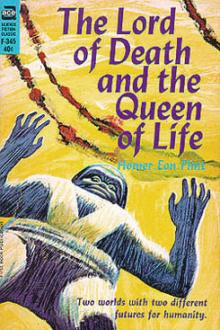

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [some good books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [some good books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

He was built much like Estra, but shorter, and with a little more flesh about the torso. His forehead bulged directly over his eyes, instead of above his ears, as did Estra's; also his eyes were smaller and not as far apart. His whole expression was equally kind and affable, despite a curiously shriveled appearance of his lips; they made the front of his mouth quite flat, and served to take attention away from his pitifully thin legs.

Estra greeted him with a cheery phrase, in a language decidedly different from any the explorers were familiar with. In a way, it was Spanish, or, rather, the pure Castilian tongue; but it seemed to be devoid of dental consonants. It was very agreeable to listen to.

Estra, however, had taken the four parcels from his comrade, and now presented him to the four, saying that his name was Kalara, and that he was a machinist. "He cannot use your tongue," said the Venusian. "Few of us have mastered it. There are difficulties.

"As for these machines"—unwrapping the parcels—"I must apologize in advance for certain defects in their design. I invented them under pressure, so to speak, having to perfect the whole idea in the rather short time that has elapsed since you, doctor, began the sky-car."

"And what is the purpose of the machines?" from Billie, as she was about to accept the first of the devices from the Venusian.

For some reason he appeared to be especially interested in the girl, and addressed half of his remarks to her; and it was while his smiling gaze was fixed upon her eyes that he gave the answer:

"They are to serve"—very carefully—"partly as lexicons and partly as grammars. In short, they are mechanical interpreters."

VI THE TRANSLATING MACHINES"First, let me remind you," said the Venusian, "of our lack of certain elements that you are familiar with on the Earth. We have never been able to improve on the common telephone. That is why we must still assemble in person whenever we have any collective activity; while on the Earth the time will come when your wireless principle will be developed to the point of transmitting both light and sound; and after that there will be little need of gatherings of any sort."

Then he explained the apparatus. It consisted of a miniature head-telephone, connected to a small, metallic case the size of a cigar-box, the cover of which was a transparent diaphragm. Estra did not open the case, but showed the mechanism through the cover.

"Essentially, this is a 'word-for-word' device," said he, pointing to a swiftly revolving dial within the box. "On one face of that dial are some ten thousand word-images, made by vibration, after the phonograph method. Directly opposite, on the other face, are the corresponding words in the other language. The disk is rotating at such an enormous speed that, for all practical purposes, any word which may chance to be spoken will be translated almost instantaneously."

He indicated two delicate, many-tentacled "feelers," as he called them, one on each face of the disk. One of these "felt" the proper word-image as it whirled beneath, while the other established an electrical contact with the corresponding waves beneath, at the same time exciting a complicated-looking talking machine.

"That," commented Estra, "is not so easy to explain. It transforms this literal translation into an idiomatic one. Perhaps you will understand its workings a little later when you learn how and why I am able to use your own language."

By this time the four had reached the point where nothing could surprise them. They were becoming accustomed to the unaccustomed. Had they been told that the Venusians had abolished speech altogether, they would have felt disappointed, but not incredulous. However, the doctor thought of something.

"Have you any extra 'records,' to be used in case we visit some other nations while we are here?"

For just a second the Venusian was puzzled; then his smile broadened. "The one record will do," said he, "wherever you go."

"A universal language!" Billie's eyes sparkled with interest.

"Long, long ago," Estra said. "It was established soon after our league of nations was formed."

"Does the league actually prevent war and promote peace?" demanded Van Emmon. This had been a disputed question when the four left the earth.

"We no longer have a league of nations," said their guide slowly. And instantly the four were eying him eagerly. This was really refreshing, to find that the Venusians were actually lacking in something.

"So it didn't work?" commented the doctor, disappointed.

But the Venusian's smile was still there. "It worked itself out," said he. "We have no further use for a league. We have no more nations. We are now—one."

And he helped them adjust the machines.

The cases were slung over their shoulders and the telephones clamped to their ears. When all ready, Estra began to talk, and his voice came nearly as sharp and clear through the apparatus as before. It was modified by a metallic flatness, together with a certain amount of mechanical noise in which a peculiar hissing was the most noticeable. Otherwise he said:

"I am now using my own language. If I make any mistakes, you must not blame the machine. It is as nearly perfect as I was able to make it."

He then asked them what blunders they noted. Billie, who was the most enthusiastic about the thing, declared that they would have no trouble in understanding; whereupon Estra quietly asked:

"Do you feel like going now to try them out?"

Once more an exchange of glances between the four from the earth. Clearly the Venusians were extremely considerate people, to leave their visitors in the care of the one man, apparently, who was able to make them feel at home. There seemed to be no reason for uneasiness.

But Van Emmon still had his old misgivings about Estra. There was something about the effeminate Venusian which irritated the big geologist; it always does make a strong man suspicious to see a weaker one show such self-confidence. Van Emmon drew the doctor and Billie aside, while Smith and Estra went on with the test. Said Van Emmon:

"It just occurred to me that the cube might look pretty good to these people. You remember what this chap said about their lack of some of our chemicals. What do you think—is it really safe to put ourselves entirely in their power?"

"You mean," said the doctor slowly, "that they might try to keep us here rather than lose the cube?"

Van Emmon nodded gravely, but Billie had strong objections. "Estra doesn't look like that sort," she declared vehemently.

"He's too good natured to be a crook; he needs a guardian rather than a warden."

It flashed into the doctor's mind that many a woman had fallen in love with a man merely because he seemed to be in need of some one to take care of him.

That is, the self-reliant kind of woman; and Billie certainly was self-reliant. Something of the same notion came vaguely to the geologist at the same time; and with a vigor that was quite uncalled for, he urged:

"I say, 'safety first.' We shouldn't have left the cube unguarded. I propose that one of us, at least, return to the surface while the others attend this meeting—or trap, for all we know."

"All right," said Billie promptly. "Get Estra to show you how to use the elevator, and wait for us in the vestibule."

Van Emmon's face flamed. "That isn't what I meant!" hotly. "If anybody goes to the cube, it should be you, Billie!"

If Billie did not notice the use of her nickname, at least the doctor did. The girl simply snorted.

"If you think for one second that I'm going to back out just because I'm a woman, let me tell you that you're very badly mistaken!"

Van Emmon turned to the doctor appealingly, but the doctor took the action personally. He shook his head. "I wouldn't miss this for anything, Van. Estra looks safe to me. Go and ask Smith; maybe he is willing to be the goat."

The geologist took one good look at the engineer's absorbed, unquestioning manner as he listened to the Venusian, and gave up the idea with a sigh. For a moment he was sour; then he smiled shyly.

"I'm more than anxious to meet the bunch myself," he admitted; and led the way back to Estra. The Venusian looked at him with no change of expression, although there was something very disconcerting in the precocious wisdom of his eyes. Their very kindliness and serenity gave him an appearance of superiority, such as only aggravated the geologist's suspicions.

But there was nothing to do but to trust him. They followed him through two sets of doors, which slid noiselessly open before them in response to some mechanism operated by the Venusian's steps. This brought them to another of the glass elevators, in which they descended perhaps ten feet, stepping out of it onto a moving platform; this, in turn, extended the length of a low dimly lighted passageway about a hundred yards long. When they got off, they were standing in a small anteroom.

The Venusian paused and smiled at the four again. "Do you feel like going on display now?" he asked; then added: "I should have said: 'Do you feel like seeing Venus on display, for we all know more or less about you already.'"

But the visitors were braced for the experience. Estra looked at each approvingly, and then did something which made them wonder. He stood stock still for perhaps a second, his eyes closed as though listening; and then, without explanation, he led the way through an opal-glass door into a brilliantly lighted space.

Next moment the explorers were standing in the midst of the people of Venus.

VII THE ULTIMATE RACEThe four were at the bottom of a huge, conelike pit, such as instantly reminded the doctor of a medical clinic. The space where they stood was, perhaps, twenty feet in diameter, while the walls enclosing the whole hall were many hundreds of feet apart. And sloping up from the center, on all sides, was tier upon tier of the most extraordinary seats in all creation.

For each and every one of those thousands of Venusians was separately enclosed in glass. Nowhere was there a figure to be seen who was not installed in one of those small, transparent boxes, just large enough for a single person. Moreover—and it came somewhat as a shock to the four when they noted it—the central platform itself was both covered and surrounded with the same material.

"Make yourselves at home," Estra was saying. He pointed to several microphones within easy reach. "These are provided with my translators, so when you are ready to open up conversation, go right ahead as though you were among your own people." And he made himself comfortable in a saddlelike chair, as much as to say that there was no hurry.

For a long time the explorers stood taking it in. The Venusians, without exception, stared back at them with nearly equal curiosity. And despite the extraordinary nature of the proceeding, this mutual scrutiny took place in comparative silence; for while the glass gave a certain sense of security to the newcomers, it also cut off all sound except that low humming.

The nearest row of the people got their closest attention. Without exception, they had the same general build as Estra; slim, delicate, and anemic, they resembled a "ward full of convalescent consumptives," as the doctor commented under his breath. Not one of them would ever give a joke-smith material for a fat-man anecdote; at the same time there was nothing feverish, nervous, or broken down in their appearance. "A pretty lot of invalids," as Billie added to the doctor's remark.

Many observers would have been struck, first, by the extreme diversity in the matter of dress. All wore skin-tight clothing, and much of it was silky, like Estra's. But there was a bewildering assortment of colors, and the most extraordinary decorations, or, rather, ornaments. So far as dress went, there was no telling anything whatever about sex.

"Are they all men?" asked Billie, wondering, of Estra. The Venusian shook his head with his invariable smile. "Nor all women either," said he enigmatically.

But in many respects they were astonishingly alike. Almost to a soul their upper lips were withered and flat. One and all had short, emaciated-looking legs. Each and every one had a crop of really luxuriant hair; the shades varied between the usual blonde and brunette, with little of the reddishness so common on the earth; but there were no bald people at all. On the other hand, there were no beards or mustaches in the whole crowd; every face was bare!

"Like a lot of Chinamen," said Van Emmon in an undertone; "can't tell one from another." But Billie pointed out that this was

Comments (0)