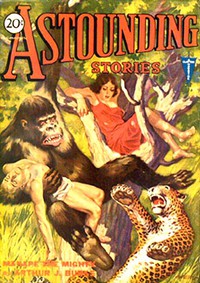

Astounding Stories, June, 1931, Various [10 best books of all time .TXT] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories, June, 1931, Various [10 best books of all time .TXT] 📗». Author Various

He had mentioned Maida to me, so I added: "And you and Maida can be married, and can live like a king and queen on what my outfit can pay you."

He smiled at me as he might have done toward a child. "Like a king and queen," he said. "But, friend Bob, Maida and I do not approve of kings and queens, nor do we wish to follow them in their follies.

"It is hard waiting,"—I saw his eyes cloud for a moment—"but Maida is willing. She is working, too—she is up in Melford as you know—and she has faith in my work. She sees with me that it will mean the release of our fellow-men and women from the poverty that grinds out their souls. I am near to success; and when I give to the world the secret of power, then—" But I had to read in his far-seeing eyes the visions he could not compass in words.

hat was the first time. I was flying a new ship when next I dropped in on him. A sweet little job I thought it then, not like the old busses that Paul and I had trained in at college, where the top speed was a hundred and twenty. This was an A. B. Clinton cruiser, and the "A.B.C.'s" in 1933 were good little wagons, the best there were.

I asked Paul to take a hop with me and fly the ship. He could fly beautifully; his lameness had been no hindrance to him. In his slender, artist hands a ship became a live thing.

"Are you doing any flying?" I asked, but the threadbare suit made his answer unnecessary.

"I'll do my flying later," he said, "and when I do,"—he waved contemptuously toward my shining, new ship—"you'll scrap that piece of junk."

The tone matched the new lines in his face—deep lines and bitter. This practical world has always been hard on the dreamers.

Poverty; and the grinding struggle that Maida was having; the expulsion from college when he was assured of a research scholarship that would have meant independence and the finest of equipment to work with—all this, I found, was having its effect. And he talked in a way I didn't like of the new Russia and of the time that was near at hand when her communistic government should sweep the world of its curse of capitalistic control. Their propaganda campaign was still going on, and I gathered that Paul had allied himself with them.

I tried to tell him what we all[359] knew; that the old Russia was gone, that Vornikoff and his crowd were rapacious and bloodthirsty, that their real motives were as far removed from his idealism as one pole from the other. But it was no use. And I left when I saw the light in his eyes. It seemed to me then that Paul Stravoinski had driven his splendid brain a bit beyond its breaking point.

nother year—and Paris, in 1939, with the dreaded First of May drawing near. There had been rumors of demonstrations in every land, but the French were prepared to cope with them—or so they believed.... Who could have coped with the menace of the north that was gathering itself for a spring?

I saw Paul there. It lacked two days of the First of May, and he was seated with a group of industrious talkers at a secluded table in a cafe. He crossed over when he saw me, and drew me aside. And I noticed that a quiet man at a table nearby never let us out of his sight. Paul and his companions, I judged, were under observation.

"What are you doing here now?" he asked. His manner was casual enough to anyone watching, but the tense voice and the look in his eyes that bored into me were anything but casual.

My resentment was only natural. "And why shouldn't I be here attending to my own affairs? Do you realize that you are being rather absurd?"

He didn't bother to answer me directly. "I can't control them," he said. "If they would only wait—a few weeks—another month! God, how I prayed to them at—"

He broke off short. His eyes never moved, yet I sensed a furtiveness as marked as if he had peered suspiciously about.

Suddenly he laughed aloud, as if at some joking remark of mine; I knew it was for the benefit of those he had left and not for the quiet man from the Surete. And now his tone was quietly conversational.

"Smile!" he said. "Smile, Bob!—we're just having a friendly talk. I won't live another two hours if they think anything else. But, Bob, my friend—for God's sake, Bob, leave Paris to-night. I am taking the midnight plane on the Transatlantic Line. Come with me—"

One of the group at the table had risen; he was sauntering in our direction. I played up to Paul's lead.

"Glad I ran across you," I told him, and shook his extended hand that gripped mine in an agony of pleading. "I'll be seeing you in New York one of these days; I am going back soon."

ut I didn't go soon enough. The unspoken pleading in Paul Stravoinski's eyes lost its hold on me by another day. I had work to do; why should I neglect it to go scuttling home because someone who feared these swarming rats had begged me to run for cover? And the French people were prepared. A little rioting, perhaps; a pistol shot or two, and a machine-gun that would spring from nowhere and sweep the street—!

We know now of the document that the Russian Ambassador delivered to the President of France, though no one knew of it then. He handed it to the portly, bearded President at ten o'clock on the morning of April thirtieth. And the building that had housed the Russian representatives was empty ten minutes later. Their disguises must have been ready, for if the sewers of Paris had swallowed them they could have vanished no more suddenly.

And the document? It was the same in substance as those delivered in like manner in every capital of Europe: twenty-four hours were[360] given in which to assure the Central Council of Russia that the French Government would be dissolved, that communism would be established, and that its executive heads would be appointed by the Central Council.

And then the bulletins appeared, and the exodus began. Papers floated in the air; they blew in hundreds of whirling eddies through the streets. And they warned all true followers of the glorious Russian faith to leave Paris that day, for to-morrow would herald the dawn of a new heaven on earth—a Communistic heaven—and its birth would come with the destruction of Paris....

I give you the general meaning though not the exact words. And, like the rest, I smiled tolerantly as I saw the stream of men and women and frightened children that filtered from the city all that day and night; but I must admit that our smiles were strained as morning came on the First of May, and the hour of ten drew near.

Paris, the beautiful—that lovely blossom, flowering on the sturdy stalk that was La Belle France! Paris, laughing to cover its unspoken fears that morning in May, while the streets thudded to the feet of marching men in horizon blue, and the air above was vibrant with the endless roar of planes.

This meant war; and mobilization orders were out; yet still the deadly menace was blurred by a feeling of unreality. A hoax!—a huge joke!—it was absurd, the thought of a distant people imposing their will upon France! And yet ... and yet....

here were countless eyes turned skyward as a thousand bells rang out the hour of ten; and countless ears heard faintly the sound of gunfire from the north.

My work had brought me into contact with high officials of the French Government; I was privileged to stand with a group of them where a high-roofed building gave a vantage point for observation. With them I saw the menacing specks on the horizon; I saw them come on with deadly deliberation—come on and on in an ever-growing armada that filled the sky.

Wireless had brought the report of their flight high over Germany; it was bringing now the story of disaster from the northern front. A heavy air-force had been concentrated there; and now the steady stream of radio messages came on flimsy sheets to the group about me, while they clustered to read the incredible words. They cursed and glared at one another, those French officials, as if daring their fellows to believe the truth; then, silent and white of face, they reached numbly for each following sheet that messengers brought—until they knew at last that the air-force of France was no more....

The roar of the approaching host was deafening in our ears. Red—red as blood!—and each unit grew to enormous proportions. Armored cruisers of the air—dreadnaughts!—they came as a complete surprise.

"But the city is ringed with anti-aircraft batteries," a uniformed man was whispering. "They will bring the brutes down."

The northern edge of the city flamed to a roaring wall of fire; the batteries went into action in a single, crashing harmony that sang triumphantly in our ears. A few of the red shapes fell, but for each of these a hundred others swept down in deadly, directed flight.

A glass was in my hand; my eyes strained through it to see the silvery cylinders that fell from the speeding ships. I saw the red cruisers sweep upward before the inferno of exploding bombs raged toward them from below. And where the roar of batteries had been was only silence.[361]

he fleet was over the city. We waited for the rain of bombs that must come; we saw the red cloud move swiftly to continue the annihilation of batteries that still could fire; we saw the armada pass on and lose itself among cloud-banks in the west.

Only a dozen planes remained, high-hung in the upper air. We stared in wonderment at one another. Was this mercy?—from such an enemy? It was inconceivable!

"Mercy!" I wonder that we dared to think the word. Only an instant till a whistling shriek marked the coming of death. It was a single plane—a giant shell—that rode on wings of steel. It came from the north, and I saw it pass close overhead. Its propeller screamed an insolent, inhuman challenge. Inhuman—for one glance told the story. Here was no man-flown plane: no cockpit or cabin, no gunmounts. Only a flying shell that swerved and swung as we watched. We knew that its course was directed from above; it was swung with terrible certainty by a wireless control that reached it from a ship overhead.

Slowly it sought its target: deliberately it poised above it. An instant, only, it hung, though the moment, it seemed, would never end—then down!—and the blunt nose crashed into the Government buildings where at that moment the Chamber of Deputies was in session ... and where those buildings had been was spouting masonry and fire.

A man had me by the arm; his fingers gripped into my flesh. With his other hand he was pointing toward the north. "Torpedoes!" he was saying. "Torpedoes of a size gigantic! Ah, mon Dieu! mon Dieu! Save us for we are lost!"

They came in an endless stream, those blood-red projectiles; they announced their coming with shrill cries of varying pitch; and they swung and swerved, as the ships above us picked them up, to rake the city with mathematical precision.

Incendiary, of course: flames followed every shattering burst. Between us and the Seine was a hell of fire—a hell that contained unnumbered thousands of what an instant before had been living folk—men and women clinging in a last terrified embrace—children whose white faces were hidden in their mothers' skirts or buried in bosoms no longer a refuge for childish fears. I saw it as plainly as if I had been given the far-reaching vision of a god ... and I turned and ran with stumbling feet where a stairway awaited....

f that flight, only a blurred recollection has stayed with me. I pray God that I may never see it more clearly. There are sights that mortal eyes cannot behold with understanding and leave mortal brain intact. It is like an anaesthetic at such times, the numbness that blocks off the horrors the eyes are recording—like the hurt of the surgeon's scalpel that never reaches to the

Comments (0)