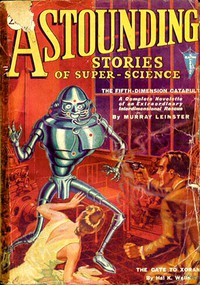

Astounding Stories, March, 1931, Various [e reader comics .txt] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories, March, 1931, Various [e reader comics .txt] 📗». Author Various

The body of Polter lay at my feet. It was hardly the length of my forearm I stood, a titan.

And then, with a shock of realization, I saw how tiny I was! This was the broken top of that fragment of golden quartz the size of a walnut! I was standing there, under the lens of the giant microscope in Polter's dome-room laboratory, with half a dozen astounded Quebec police officials peering down at me![358]

CHAPTER XII Mysterious Little Golden Rockneed not detail the aftermath of our emergence from the atom. Dr. Kent and Babs followed me out within a few moments. But Alan was not with them! He had seen Polter fall. His father and Babs were safe. The sacrifice he had made in leaving Glora was no longer needed.

Down there on the rocky plateau, Dr. Kent suddenly realized that Alan was dwindling.

"Father, I must! Don't you understand? Glora's world is menaced. I can't leave her like this. My duty to you and Babs is ended. I did my best, Dad—you two are safe now."

"Alan! My boy!"

He was already down at Dr. Kent's waist, Bab's size. He held up his hand. "Dad, good-by." His rugged, youthful face was flushed, his voice choked. "You—you've been a mighty good father to me. Always."

Babs flung her arms about him. "Alan, don't!"

"But I must." He smiled whimsically as he kissed her. "You wouldn't want to leave George, would you? Never see him again? I'm not asking you to do that, am I?"

"But, Alan—"

"You've been a great little pal, Babs. I'll never forget it."

"Alan! You talk as though you were never coming back!"

"Do I? But of course I'm coming back!" He cast her off. "Babs, listen. Father's upset. That's natural. You tell him not to worry. I'll be careful, and do what I can to save that little city. I must find Glora and—"

Babs was suddenly trembling with eagerness for him. "Yes! Of course you must, Alan!"

"Find her and bring her out here! I'll do it! Don't you worry." He was dwindling fast. Dr. Kent had collapsed to a rock, staring down with horror-stricken eyes. Alan called up to Babs:

"Listen! Have George watch the chunk of gold-quartz. Have it guarded and watched day and night. Handle it carefully, Babs!"

"Yes! Yes! How long will you be gone, Alan?"

"Heavens—how do I know? But I'll come back, don't you worry. Maybe in only a day or two of your time."

"Right! Good-by, Alan!"

"Good-by," his tiny voice echoed up. "Good-by, Babs—Father!"

Babs could see his miniature face smiling up at her. She smiled back and waved her arm as he vanished into the pebbles at her feet.

The eyes of youth! They look ahead; they see all things so easily possible! But old Dr. Kent was sobbing.

t has broken Dr. Kent. A month now has passed. He seldom mentions Alan to Babs and me. But when he does, he tries to smile and say that Alan soon will return. He has been very ill this last week, though he is better now. He did not tell us that he was working to compound another supply of the drugs, but we knew it very well.

And his emotion, the strain of it, made him break. He was in bed a week. We are living in New York, quite near the Museum of the American Society for Scientific Research. In a room of the biological department there, the precious fragment of golden quartz lies guarded. A microscope is over it, and there is never a moment of the day or night without an alert, keen-eyed watcher peering down.

But nothing has appeared. Neither friend nor foe—nothing. I cannot say so to Babs, but often I fear that Dr. Kent will suddenly die, and the secret of his drugs die with him. I hinted once that I would make a trip into the atom if he would let me, but it excited him so greatly I had to laugh it off with the assurance that of course Alan will soon return safely to us. Dr. Kent is an old man now, unnaturally old, with, it seems, the full weight of eighty years[359] pressing upon him. He cannot stand this emotion. I think he is despairingly summoning strength to work upon his drugs, fearful that he will not be equal to it. Yet more fearful to disclose the secret and unloose so diabolical a power.

There are nights when with Dr. Kent asleep, Babs and I slip away and go to the Museum. We dismiss the guard for a time, and in that private room we sit hand in hand by the microscope to watch. The fragment of golden quartz lies on its clean white slab with a brilliant light upon it.

Mysterious little golden rock! What secrets are there, down beyond the vanishing point in the realm of the infinitely small! Our human longings go to Alan and to Glora.

But sometimes we are swept by the greater viewpoint. Awed by the mysteries of nature, we realize how very small and unimportant we are in the vast scheme of things. We envisage the infinite reaches of astronomical space overhead. Realms of largeness unfathomable. And at our feet, everywhere, are myriad entrances into the infinitely small. With ourselves in between—with our fatuous human consciousness that we are of some importance to it all!

Truly there are more things in Heaven and Earth than are dreamed of in our philosophy!

INVISIBLE EYES

n invisible eye that can see in the dark and detect the light of a ship two miles away on a black foggy night was introduced to newspaper men recently by its inventor, John Baird of television fame. He calls the invention "Noctovisor."

It looks like a large camera and can be mounted on a ship or airplane. It was announced that it would soon be tried on trans-Atlantic liners. For the demonstration it was mounted in the garden of Baird's cottage, overlooking the twinkling lights of Dorking. In the dark beyond those lights an automobile headlight three miles away pointed toward the cottage.

At a signal from the inventor a sheet of ebonite, as a substitute for a supposed fog, two miles thick, was placed in front of the headlight. Not a glimmer was then visible to the human eye, but it appeared on the noctovisor screen as a bright red disc. It was supposed to have particular value in permitting a navigator in a fog to tell the exact direction of a beacon and to estimate roughly its distance.

The device is a combination of camera lens, television transmitter and television receiver. The lens throws a distant image on the exploring disc of the transmitter, through which it acts on a photo-electric cell sensitive to invisible infra-red rays. The receiver amplifies it for the observer.

MOON ROCKETSeventeen years of experimenting on a rocket designed by Prof. Albert H. Goddard of Clark University, to shriek its way from the earth to the moon, came to a glorious climax recently in an isolated and closely guarded section of Worcester when the rocket tore its flaming way through the air for a quarter-mile with a roar heard for a distance of two miles.

Prof. Goddard said the rocket was shot out of its cradle, careened through the air a mass of flame, and landed about where it was directed to land, beyond the Auburn town line. Test of a new propellant was the object of his demonstration, Prof. Goddard said.

Two or three times a week a small rocket goes up into the air a short distance, not enough to attract great attention. But the latest was a nine-foot rocket, shot out of a forty-foot tower. Near the tower is a safety post built of stone, with slits for peepholes. The experimental party stepped into the safety zone when the rocket was started.

The forty-foot tower is built much like an oil well derrick. Inside it are two steel rails to fill grooves in the rocket. These guide the rocket much as rifling in a gun barrel guides a bullet. Prof. Goddard, when teaching at Princeton in 1912, evolved the idea of shooting a rocket to the moon by means of successive charges of explosive much as the new German rocket motor racers are powered. In this most recent experiment he used a new powder mixture.

Prof. Goddard issued a statement after the demonstration, which said:

"My test was one of a series of experiments with rockets using an entirely new propellant. There was no attempt to reach the moon or anything of such a spectacular nature. The rocket is normally noisy, possibly enough to attract considerable attention. The test was thoroughly satisfactory, nothing exploded in the air, and there was no damage except possibly that incidental to landing."

[360]

"Eddie!" Lisa screamed suddenly. "Look out!"

Terrors Unseen

By Harl Vincent

"Eddie!" Lisa screamed suddenly. "Look out!"

Terrors Unseen

By Harl Vincent

omething about the lonely figure of the girl caused Edward Vail to bring his car to a sudden stop at the side of the road. When first he had glimpsed her off there on that narrow strip of rock-bound coast he was mildly surprised, for it was a desolate spot and seldom frequented by bathers so late in the season. Now he was aroused to startled attention by the unnatural posture of the slender body that had just been erect and outlined sharply against the graying September sky. He switched off the ignition and sprang to the ground.

Bent backward and twisted into the attitude of a contortionist, the little figure in the crimson bathing suit was a thing at which to marvel. No human being could maintain that position without falling, yet the[361] girl did not fall to the jagged stones that lay beneath her. She was rigid, straining. Then suddenly her arm waved wildly and she screamed, a wild gasping cry that died in her throat on a note of despairing terror. It seemed that she struggled furiously with an unseen power for one horrible instant. Then the tortured body lurched violently and collapsed in a pitiful quivering heap among the stones.

Eddie Vail was running now, miraculously picking his way over the treacherous footing. The girl had fainted, no doubt of that, and something was seriously wrong with her.

A mysterious mechanical something whizzed past; something that buzzed like a thousand hornets and slithered over the rocks in a series of metallic clanks. Then it was gone—or so it seemed in the confusion of Eddie's mind; but he had seen nothing. Probably a fantasy of his overworked brain, or only the surf breaking against the sea wall. He turned his attention to the girl.

he was moaning and tossing her head, returning painfully to consciousness. He straightened her limbs and placed his folded coat under the restless head, noting with alarm that vicious red welts marred the whiteness of her arms and shoulders. It was as if she had been beaten cruelly; those marks could never have resulted from her fall. Poor kid. Subject to fits of some sort, he presumed. She was a good looker, too, and no mistake. He smoothed back the rumpled mass of golden hair and studied her features. They were vaguely familiar.

Then she opened her eyes. Stark terror looked out from their ultra-marine depths, and her lips quivered as if she were about to cry. He raised her to a more comfortable position and supported her with an encircling arm. She did cry a little, like a frightened child. Then, with startling abruptness, she sprang to her feet.

"Where is it?" she demanded.

"Where's what?" Eddie was on his feet, peering in all directions. He remembered the queer sounds he had heard or imagined.

"I—I don't know." The girl passed a trembling hand before her eyes as if to wipe away some horrifying vision. "Perhaps it's my imagination, but I felt—it was just as real—one of father's iron monsters. Beating me; bending me. I'd have snapped in a moment. But nothing was there. I—I'm afraid...."

Eddie caught her as she swayed on her feet. "There now," he said soothingly, "you're all right, Miss Shelton. It's gone now, whatever it was." Iron monsters! In a flash it had come to him that this girl he held in his arms was Lina Shelton, daughter of the robot wizard. No wonder she was afflicted with hallucinations! But

Comments (0)