Out of Time's Abyss, Edgar Rice Burroughs [english reading book txt] 📗

- Author: Edgar Rice Burroughs

Book online «Out of Time's Abyss, Edgar Rice Burroughs [english reading book txt] 📗». Author Edgar Rice Burroughs

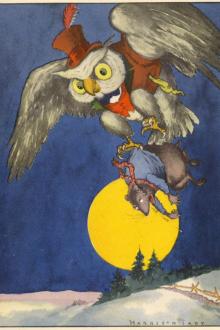

"Gawd!" he almost screamed. "What is it?"

Attracted by Brady's cry the others seized their rifles as they followed his wide-eyed, frozen gaze, nor was there one of them that was not moved by some species of terror or awe. Then Brady spoke again in an almost inaudible voice. "Holy Mother protect us—it's a banshee!"

Bradley, always cool almost to indifference in the face of danger, felt a strange, creeping sensation run over his flesh, as slowly, not a hundred feet above them, the thing flapped itself across the sky, its huge, round eyes glaring down upon them. And until it disappeared over the tops of the trees of a near-by wood the five men stood as though paralyzed, their eyes never leaving the weird shape; nor never one of them appearing to recall that he grasped a loaded rifle in his hands.

With the passing of the thing, came the reaction. Tippet sank to the ground and buried his face in his hands. "Oh, Gord," he moaned. "Tyke me awy from this orful plice." Brady, recovered from the first shock, swore loud and luridly. He called upon all the saints to witness that he was unafraid and that anybody with half an eye could have seen that the creature was nothing more than "one av thim flyin' alligators" that they all were familiar with.

"Yes," said Sinclair with fine sarcasm, "we've saw so many of them with white shrouds on 'em."

"Shut up, you fool!" growled Brady. "If you know so much, tell us what it was after bein' then."

Then he turned toward Bradley. "What was it, sir, do you think?" he asked.

Bradley shook his head. "I don't know," he said. "It looked like a winged human being clothed in a flowing white robe. Its face was more human than otherwise. That is the way it looked to me; but what it really was I can't even guess, for such a creature is as far beyond my experience or knowledge as it is beyond yours. All that I am sure of is that whatever else it may have been, it was quite material—it was no ghost; rather just another of the strange forms of life which we have met here and with which we should be accustomed by this time."

Tippet looked up. His face was still ashy. "Yer cawn't tell me," he cried. "Hi seen hit. Blime, Hi seen hit. Hit was ha dead man flyin' through the hair. Didn't Hi see 'is heyes? Oh, Gord! Didn't Hi see 'em?"

"It didn't look like any beast or reptile to me," spoke up Sinclair. "It was lookin' right down at me when I looked up and I saw its face plain as I see yours. It had big round eyes that looked all cold and dead, and its cheeks were sunken in deep, and I could see its yellow teeth behind thin, tight-drawn lips—like a man who had been dead a long while, sir," he added, turning toward Bradley.

"Yes!" James had not spoken since the apparition had passed over them, and now it was scarce speech which he uttered—rather a series of articulate gasps. "Yes—dead—a—long—while. It—means something. It—come—for some—one. For one—of us. One—of us is goin'—to die. I'm goin' to die!" he ended in a wail.

"Come! Come!" snapped Bradley. "Won't do. Won't do at all. Get to work, all of you. Waste of time. Can't waste time."

His authoritative tones brought them all up standing, and presently each was occupied with his own duties; but each worked in silence and there was no singing and no bantering such as had marked the making of previous camps. Not until they had eaten and to each had been issued the little ration of smoking tobacco allowed after each evening meal did any sign of a relaxation of taut nerves appear. It was Brady who showed the first signs of returning good spirits. He commenced humming "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" and presently to voice the words, but he was well into his third song before anyone joined him, and even then there seemed a dismal note in even the gayest of tunes.

A huge fire blazed in the opening of their rocky shelter that the prowling carnivora might be kept at bay; and always one man stood on guard, watchfully alert against a sudden rush by some maddened beast of the jungle. Beyond the fire, yellow-green spots of flame appeared, moved restlessly about, disappeared and reappeared, accompanied by a hideous chorus of screams and growls and roars as the hungry meat-eaters hunting through the night were attracted by the light or the scent of possible prey.

But to such sights and sounds as these the five men had become callous. They sang or talked as unconcernedly as they might have done in the bar-room of some publichouse at home.

Sinclair was standing guard. The others were listening to Brady's description of traffic congestion at the Rush Street bridge during the rush hour at night. The fire crackled cheerily. The owners of the yellow-green eyes raised their frightful chorus to the heavens. Conditions seemed again to have returned to normal. And then, as though the hand of Death had reached out and touched them all, the five men tensed into sudden rigidity.

Above the nocturnal diapason of the teeming jungle sounded a dismal flapping of wings and over head, through the thick night, a shadowy form passed across the diffused light of the flaring camp-fire. Sinclair raised his rifle and fired. An eerie wail floated down from above and the apparition, whatever it might have been, was swallowed by the darkness. For several seconds the listening men heard the sound of those dismally flapping wings lessening in the distance until they could no longer be heard.

Bradley was the first to speak. "Shouldn't have fired, Sinclair," he said; "can't waste ammunition." But there was no note of censure in his tone. It was as though he understood the nervous reaction that had compelled the other's act.

"I couldn't help it, sir," said Sinclair. "Lord, it would take an iron man to keep from shootin' at that awful thing. Do you believe in ghosts, sir?"

"No," replied Bradley. "No such things."

"I don't know about that," said Brady. "There was a woman murdered over on the prairie near Brighton—her throat was cut from ear to ear, and—"

"Shut up," snapped Bradley.

"My grandaddy used to live down Coppington wy," said Tippet. "They were a hold ruined castle on a 'ill near by, hand at midnight they used to see pale blue lights through the windows an 'ear—"

"Will you close your hatch!" demanded Bradley. "You fools will have yourselves scared to death in a minute. Now go to sleep."

But there was little sleep in camp that night until utter exhaustion overtook the harassed men toward morning; nor was there any return of the weird creature that had set the nerves of each of them on edge.

The following forenoon the party reached the base of the barrier cliffs and for two days marched northward in an effort to discover a break in the frowning abutment that raised its rocky face almost perpendicularly above them, yet nowhere was there the slightest indication that the cliffs were scalable.

Disheartened, Bradley determined to turn back toward the fort, as he already had exceeded the time decided upon by Bowen Tyler and himself for the expedition. The cliffs for many miles had been trending in a northeasterly direction, indicating to Bradley that they were approaching the northern extremity of the island. According to the best of his calculations they had made sufficient easting during the past two days to have brought them to a point almost directly north of Fort Dinosaur and as nothing could be gained by retracing their steps along the base of the cliffs he decided to strike due south through the unexplored country between them and the fort.

That night (September 9, 1916), they made camp a short distance from the cliffs beside one of the numerous cool springs that are to be found within Caspak, oftentimes close beside the still more numerous warm and hot springs which feed the many pools. After supper the men lay smoking and chatting among themselves. Tippet was on guard. Fewer night prowlers threatened them, and the men were commenting upon the fact that the farther north they had traveled the smaller the number of all species of animals became, though it was still present in what would have seemed appalling plenitude in any other part of the world. The diminution in reptilian life was the most noticeable change in the fauna of northern Caspak. Here, however, were forms they had not met elsewhere, several of which were of gigantic proportions.

According to their custom all, with the exception of the man on guard, sought sleep early, nor, once disposed upon the ground for slumber, were they long in finding it. It seemed to Bradley that he had scarcely closed his eyes when he was brought to his feet, wide awake, by a piercing scream which was punctuated by the sharp report of a rifle from the direction of the fire where Tippet stood guard. As he ran toward the man, Bradley heard above him the same uncanny wail that had set every nerve on edge several nights before, and the dismal flapping of huge wings. He did not need to look up at the white-shrouded figure winging slowly away into the night to know that their grim visitor had returned.

The muscles of his arm, reacting to the sight and sound of the menacing form, carried his hand to the butt of his pistol; but after he had drawn the weapon, he immediately returned it to its holster with a shrug.

"What for?" he muttered. "Can't waste ammunition." Then he walked quickly to where Tippet lay sprawled upon his face. By this time James, Brady and Sinclair were at his heels, each with his rifle in readiness.

"Is he dead, sir?" whispered James as Bradley kneeled beside the prostrate form.

Bradley turned Tippet over on his back and pressed an ear close to the other's heart. In a moment he raised his head. "Fainted," he announced. "Get water. Hurry!" Then he loosened Tippet's shirt at the throat and when the water was brought, threw a cupful in the man's face. Slowly Tippet regained consciousness and sat up. At first he looked curiously into the faces of the men about him; then an expression of terror overspread his features. He shot a startled glance up into the black void above and then burying his face in his arms began to sob like a child.

"What's wrong, man?" demanded Bradley. "Buck up! Can't play cry-baby. Waste of energy. What happened?"

"Wot 'appened, sir!" wailed Tippet. "Oh, Gord, sir! Hit came back. Hit came for me, sir. Right hit did, sir; strite hat me, sir; hand with long w'ite 'ands it clawed for me. Oh, Gord! Hit almost caught me, sir. Hi'm has good as dead; Hi'm a marked man; that's wot Hi ham. Hit was a-goin' for to carry me horf, sir."

"Stuff and nonsense," snapped Bradley. "Did you get a good look at it?"

Tippet said that he did—a much better look than he wanted. The thing had almost clutched him, and he had looked straight into its eyes—"dead heyes in a dead face," he had described them.

"Wot was it after bein', do you think?" inquired Brady.

"Hit was Death," moaned Tippet, shuddering, and again a pall of gloom fell upon the little party.

The following day Tippet walked as one in a trance. He never spoke except in reply to a direct question, which more often than not had to be repeated before it could attract his attention. He insisted that he was already a dead man, for if the thing didn't come for him during the day he would never live through another night of agonized apprehension, waiting for the frightful end that he was positive was in store for him. "I'll see to that," he said, and they all knew that Tippet meant to take his own life before darkness set in.

Bradley tried to reason with him, in his short, crisp way, but soon saw the futility of it; nor could he take the man's weapons from him without subjecting him to almost certain death from any of the numberless dangers

Comments (0)