What Do You Read?, Boyd Ellanby [i can read book club .txt] 📗

- Author: Boyd Ellanby

Book online «What Do You Read?, Boyd Ellanby [i can read book club .txt] 📗». Author Boyd Ellanby

Carre stood in front of Number Eight in fascination as the metal arms hammered out the words and lines. After a moment, he frowned. "I seem to remember this! I must have read it in my early boyhood. It seems so long ago. Joan of Arc! But I don't remember its happening just this way."

"Just goes to show you can't trust your memory, Carre. You know the machines are perfectly logical, and they can't make a mistake."

"No, of course not. Odd, though." He brushed his hand over a forehead grown wet.

The knife flashed down, cut the paper, and the page fell into its basket. Hartridge picked it up.

"Would you like this sheet, as a memento? Number Eight can easily re-do it."

"Thank you."

"And is there anything else I can show you? I don't mind admitting I'm very proud of my machines."

"Well," said Carre, "perhaps you might let me have some of your current manuscripts, just for tonight? I can make a comparative study, for Ludwig, and return them sometime tomorrow."

"Nothing easier." He assembled a bundle of stapled sheets and put them in a box, and then rang for the guards, to show him out.

"Take care of yourself, Carre. See you tomorrow."

Herbert sat, that evening, in his book-lined room, reading manuscripts. He looked more and more puzzled, and ill at ease. He got up, after a time, to pace the room, and on a sudden impulse he left the apartment and hurried up the street.

It had grown dark outside, and he hurried. He could not stand the thought of the Airway, so he walked. He had covered nearly half a mile when, at the corner ahead, two Street-taxis approached each other at right angles. The drivers glared at each other. Neither slowed to let the other pass; they crashed, and began to burn. Carre hurried on, trying not to hear the screams of the people or the siren of the approaching ambulance. No wonder, he thought, that they need Ludwig in the Bureau of Public Safety; people were behaving so irrationally!

He climbed the steps of the City Library, and advanced to the desk.

"I should like to see files of the magazines published by Adult Fiction, Earth, if you please."

"But which magazine, sir? They publish hundreds."

"Well, as a start, let me see those which publish light fiction."

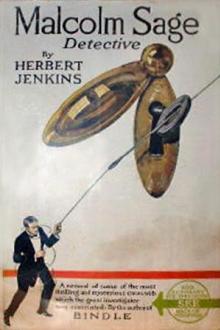

For two hours he sat in the Scholar's Room, skimming the pages of the magazines—Sagebrush Westerns, Romance and Marriage, Pinkerton's Own, Harper's, and a dozen others. He read with concentration, and made few notes. On his way home he stopped at a news-machine and selected an armful of the current issues to take home with him. He read in his room until nearly dawn, and when he did lie down he could not sleep, or rest.

"I don't believe it," he whispered to himself. "It can't be true." And, half an hour later, "How did it happen?"

At nine next morning he was sitting in the reception room of the Bureau of Public Entertainment, with brief-case on his knees, waiting for Ludwig. It was nearly noon before Ludwig himself arrived, and summoned his visitor.

He sat at his desk, his white hair rumpled, and nervously fingered his watch chain as Carre took the chair opposite.

"Sorry to keep you waiting, Herbert. The Commissioners over in Safety have a bad situation to handle, and I've been trying to advise them. I'll be glad when this writing business is straightened out, and I can give full attention to Safety. What did you think of Script-Lab?"

"Well, it's very efficient."

"I knew that," said Ludwig. "Machines are built to be efficient. But what do you think of their output? How does it compare with the work of the Writers?"

Carre cleared his throat. "John, don't you read the magazines any more?"

"No. No time. Do you?"

"I haven't, until yesterday. I read them, all night. I hardly know how to express myself. John, something is wrong with the machines."

"Nonsense! There can't be anything wrong with them. They're fed the plots, fed the variations, and then with perfect logic they create their stories. You're not an electronics expert, you know."

Carre stared at the floor. Ludwig sighed.

"I'm sorry, Herbert. I'm just too tired to be decently courteous. But what I wanted from you, after all, was a literary evaluation and not a scientific one."

"I express myself so badly. There's something wrong, something I can't exactly define, with what they write."

Ludwig looked exasperated. "But what, man? Be concrete."

"I'll try. Here's a short story that was made yesterday. Glance over it, please, and tell me how it strikes you."

Ludwig read through the manuscript with his accustomed rapidity. "I don't see anything particularly wrong about it," he said. "Murder mysteries have never been to my taste, and I don't know that I exactly approve of the hero's killing his benefactress with an undetectable poison, and then inheriting her fortune and marrying her niece. Undetectable poisons are all nonsense, anyway."

"The story doesn't seem to you—unhealthy?"

"I don't know what you're getting at! It's on the grim side, I suppose, but isn't most modern fiction a little grim? How about your own stuff?"

"I think there's a difference. I know I've written a few mysteries, and even some tragic stories, but I don't believe I've ever written anything exactly like this. And this is typical. They're doing reprints, too, of books that were destroyed or lost during the Atomic Wars. Do you remember Joan of Arc? Mark Twain's version? Here is a page from Script-Lab's manuscript."

Ludwig took the sheet and read aloud: "By-and-by a frantic man in priest's garb came wailing and lamenting and tore through the crowd and the barrier of soldiers and flung himself on his knees by Joan's cart and put up his hands in supplication, crying out—

'"O, forgive, forgive!"

'It was Loyseleur!

'And Joan's heart knew nothing of forgiveness, nothing of compassion, nothing of pity for all that suffer and have been offensive—'"

Ludwig looked up with a frown. "That's odd. It's been so long since I saw that book—I was only a boy—but that isn't just the way I remember it."

"That's what Script-Lab is writing."

"But the machines, don't—"

"I know. They don't make mistakes."

The buzz of the visi-sonor interrupted them, and the Commissioner of Public Safety spoke from the screen.

"For heaven's sake, Ludwig, shelve the book-business and get over here. We've had a rash of robberies with violence, a dozen bad street accidents, and two suspicious deaths of diabetics in coma. We need help."

Ludwig was already reaching for his brief case. "Right away," he said, and flicked the switch.

"John!" Carre begged, "This book matter is serious. You can't just drop it! Come with me to Hartridge's lab and see for yourself!"

"I can't. No time. You heard the Commissioner."

"Tomorrow morning?"

"Can't make it. Have to go to a funeral. A niece of mine who died suddenly of cancer. Poor girl. We thought she was doing so well, too, with the hormone injections. Not that her husband will break his heart, from what I know of the scoundrel."

Carre followed him towards the door. "Then make it tomorrow afternoon! It's vital!"

Ludwig pulled out his watch, and thought for a second. "All right. Meet you there tomorrow at three." The door slammed behind him.

They followed the guards through the chrome steel doors into the room with the machines. All twenty typewriters were hammering out their hundred words a minute.

"It is an honor to have a visit from you, Commissioner Ludwig," said Hartridge. "We're very proud of Script-Lab. You'll agree, I know, that the experiment has been eminently successful. Tough on you, of course, Carre. But you Writers can always land on your feet."

"The decision has not yet been made," said Ludwig. "Now to business." He pulled a chair up to the desk, opened his brief case, and took out some papers.

"Before I examine the machines, I'd like to check with you the facts and figures that Carre has compiled for me. In 1971, the first year of the experiment, only ten per cent of Script-Lab's output of stories, books, and articles was accepted by Adult Fiction, Earth. Right?"

"Right," said Hartridge. "But that was our worst year. Since then—"

Ludwig held up his hand. "In the second year, you supplied thirty-five per cent of the needs of AFE. Check?"

"Check."

"In the two years following you supplied seventy-five per cent, and in 1976, this year you are supplying about ninety per cent of all published matter, with the Writers supplying only ten per cent. Correct?"

"Correct. A wonderful record, Commissioner."

Ludwig turned to another sheet of data. "As I understand it, you feed into the machine's memories, basic plots, factual data, conversational variants, and they do the rest?"

"That's right. We give them the material, and they create with perfect rationality. I myself read nearly everything they make, and even I am amazed at their craftsmanship. And they are so efficient, and write so swiftly!"

"Speed is no doubt a desirable feature," said Ludwig.

"But not the only one!" said Carre.

Hartridge smiled. "Professional jealously is warping your judgment, old man. It may be hard to take, but you Writers have nothing to give the world, anymore, that machines can't."

Ludwig turned his back and surveyed the room. "I would like to see, now, some of your productions."

Hartridge beamed. "As a matter of fact, I have something that ought to interest you, particularly. Just follow me, gentlemen. Here, by the way, is our power source. Note how simple and efficient the circuit design is. Ah, here we are. Knowing that you were making us a visit today, I gave to Number Seven, here, the necessary data for creating your own monologue on 'Our Duties to the Aged.' That was your doctoral thesis, I believe?"

"But that's out of print! I haven't seen a copy myself in years!"

"To Script-Lab, that is unimportant. Feed it the data, the basic premises, and it will do the rest. Would you like to see?"

The three men crowded around Number Seven, and watched the emergence of paper from the typewriter as the keys tapped the words into lines, and the carriage shifted. Ludwig, at first, showed only the pleasure which any writer feels on re-reading a good piece of work. Gradually, his face changed. He looked puzzled, uncertain, and then his skin reddened with anger.

"He looked puzzled, uncertain, and then his skin reddened with anger."

The automatic knife chopped down and severed the completed page. Ludwig scooped it up from the basket and read the page a second time. He raised his eyes to meet the tense gaze of Carre.

"Is this what you were trying to tell me, Herbert?"

"That sort of thing. Yes."

"Is something wrong, Commissioner?" said Hartridge. "I thought you'd be pleased."

"Pleased? But this is something I never wrote!"

"But you must have written it," said Hartridge. "Or are you just trying to sabotage my project with a deliberate misstatement?"

"Read it!" said Ludwig. "Read that paragraph out loud."

"'Our duties to the aged,'" read Hartridge, "'are closely bound to our duties to ourselves. When the old become infirm, they should be quietly helped out of a contented existence. After all, the only measure of the value of aged men and women should be their present usefulness to society.'

He looked up from the page. "I don't see why you're so unwilling to admit your authorship, Commissioner. There's nothing wrong with this."

"Only," Ludwig said softly, "I didn't write it. What the monologue actually said was something like this: 'Our duties to the aged are closely bound to our duties to ourselves. When the old become infirm, they should be quietly helped to a contented existence. After all, the only measure of the value of aged men and women should be their past usefulness to our society.'

"You've made your point, Carre," he went on. "If this sort of perverted advice has been fed to our people the last few years, it's no wonder we're having a wave of crimes. Be selfish! It pays. An eye for an eye! Poison the old man! Nobody will ever know and you'll get his money!"

Hartridge was still studying the typescript, and he spoke with defiance. "Number Seven's excerpt from your monologue seems perfectly sensible to me," he said. "For some reason of your own you must be lying about it. Why, the version you say you remember is utterly illogical!"

"Of course it's illogical!" said

Comments (0)