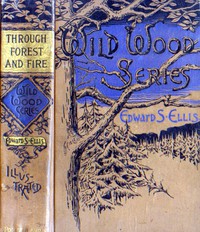

Through Forest and Fire<br />Wild-Woods Series No. 1, Edward Sylvester Ellis [smart books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis

Book online «Through Forest and Fire<br />Wild-Woods Series No. 1, Edward Sylvester Ellis [smart books to read .txt] 📗». Author Edward Sylvester Ellis

No one interfered, however, and when the conqueror thought he had flattened out the city youth to that extent that he would never acquire any plumpness again, he rose from his seat and allowed Herbert to climb upon his feet.

Never was a boy more completely cowed than was this vaunting youth, on whom all the others had looked with such admiration and awe. He meekly picked up his hat, brushed off the dirt, and looking reproachfully at Nick said:

"Do you know you broke two of my ribs?"

"I dinks I brokes dem all: dat's what I meant to do; I will try him agin."

"No, you won't!" exclaimed Herbert, darting off in a run too rapid for the short legs of Nick to equal.

Nick Ribsam had conquered a peace, and from that time forth he suffered no persecution at school. Master Herbert soon after went back to his city home, wondering how it was that a small, dumpy lad, four years younger than he, was able to vanquish him so completely when all the science was on the side of the elder youth.

Young as was Nick Ribsam, there was not a boy in the school who dared attempt to play the bully over him. The display he had given of his prowess won the respect of all.

Besides this he proved to be an unusually bright scholar. He dropped his faulty accent with astonishing rapidity, and gained knowledge with great facility. His teacher liked him, as did all the boys and girls, and when he was occasionally absent he was missed more than half a dozen other lads would have been.

The next year Nick brought his sister Nellie to school. He came down the road, holding her fat little hand in his, while her bright eyes peered out from under her plain but odd-looking hat in a timid way, which showed at the same time how great her confidence was in her big brother.

Nellie looked as much like Nick as a sister can look like a brother. There were the same ruddy cheeks, bright eyes, sturdy health, and cleanly appearance. Her gingham pantalettes came a little nearer the tops of her shoes, perhaps than was necessary, but the dress, with the waist directly under the arms, would have been considered in the height of fashion in late years.

One daring lad ventured to laugh at Nellie, and ask her whether she had on her father's or mother's shoes, but when Nick heard of it he told the boy that he would "sit down" on any one that said anything wrong to Nellie. Nothing of the kind was ever hinted to the girl again. No one wished to be "sat down" on by the Pennsylvania Hollander who banged the breath so utterly from the body of the city youth who had aroused his wrath.

The common sense, sturdy frame, sound health, and mental strength of the parents were inherited in as marked a degree by the daughter Nellie as by Nick. She showed a quickness of perception greater than that of her brother; but, as is generally the case, the boy was more profound and far-reaching in his thoughts.

After Nick had done his chores in the evening and Nellie was through helping her mother, Gustav, the father, was accustomed to light his long-handled pipe, and, as he slowly puffed it while sitting in his chair by the hearth, he looked across to his boy, who sat with his slate and pencil in hand, preparing for the morrow. Carefully watching the studious lad for a few minutes, he generally asked a series of questions:

"Nicholas, did you knowed your lessons to-day?"

"Yes, sir."

"Did you know efery one dot you knowed?"

"Yes, sir,—every one," answered Nick respectfully, with a quiet smile over his father's odd questions and sentences. The old gentleman could never correct or improve his accent, while Nick, at the age of ten, spoke so accurately that his looks were all that showed he was the child of German parents.

"Did nopody gif you helps on der lessons?"

"Nobody at all."

"Dot is right; did you help anypodies?"

"Yes, sir,—three or four of the girls and some of the boys asked me to give them a lift—"

"Gif dem vat?"

"A lift—that is, I helped them."

"Dot ish all right, but don't let me hears dot nopody vos efer helping you; if I does—"

And taking his pipe from his mouth, Mr. Ribsam shook his head in a way which threatened dreadful things.

Then the old gentleman would continue smoking a while longer, and more than likely, just as Nick was in the midst of some intricate problem, he would suddenly pronounce his name. The boy would look up instantly, all attention.

"Hef you been into any fights mit nopodies to-day?"

"I have not, sir; I have not had any trouble like that for a long while."

"Dot is right—dot is right; but, Nick, if you does get into such bad tings as fightin', don't ax nopodies to help you; takes care mit yorself!"

The lad modestly answered that he did not remember when he had failed to take care of himself under such circumstances, and the father resumed his pipe and brown study.

The honest German may not have been right in every point of his creed, but in the main he was correct, his purpose being to implant in his children a sturdy self-reliance. They could not hope to get along at all times without leaning upon others, but that boy who never forgets that God has given him a mind, a body, certain faculties and infinite powers, with the intention that he should cultivate and use them to the highest point, is the one who is sure to win in the great battle of life.

Then, too, every person is liable to be overtaken by some great emergency which calls out all the capacities of his nature, and it is then that false teaching and training prove fatal, while he who has learned to develop the divine capacities within him comes off more than conqueror.

CHAPTER III. A MATHEMATICAL DISCUSSION.The elder Ribsam took several puffs from his pipe, his eyes fixed dreamily on the fire, as though in deep meditation. His wife sat in her chair on the other side, and was busy with her knitting, while perhaps her thoughts were wandering away to that loved Fatherland which she had left so many years before, never to see again. Nellie had grown sleepy and gone to bed.

Mr. Ribsam turned his head and looked at Nick. The boy was seated close to the lamp on the table, and the scratching of his pencil on his slate and his glances at the slip of paper lying on the stand, with the problems written upon it, told plainly enough what occupied his thoughts.

"Nicholas," said the father.

"Just one minute, please," replied the lad, glancing hastily up: "I am on the last of the problems that Mr. Layton gave us for this week, and I have it almost finished."

The protest of the boy was so respectful that the father resumed his smoking and waited until Nick laid his slate on the table and wheeled his chair around.

"There, father, I am through."

"Read owed loud dot sum von you shoost don't do."

"Mr. Layton gave a dozen original problems as he called them, to our class to-day, and we have a week in which to solve them. I like that kind of work, and so I kept at it this evening until I finished them all."

"You vos sure dot you ain't right, Nicholas, eh?"

"I have proved every one of them. Oh, you asked me to read the last one! When Mr. Layton read that we all laughed because it was so simple, but when you come to study it it isn't so simple as you would think. It is this: If New York has fifty per cent. more population than Philadelphia, what per cent. has Philadelphia less than New York?"

Mr. Ribsam's shoulders went up and down, and he shook like a bowl of jelly. He seemed to be overcome by the simplicity of the problem over which his son had been racking his brains.

"Dot makes me laughs. Yaw, yaw, yaw!"

"If you will sit down and figure on it you won't laugh quite so hard," said Nick, amused by the jollity of his father, which brought a smile to his mother; "what is your answer?"

"If I hafs feefty tollar more don you hafs, how mooch less tollar don't you hafs don I hafs? Yaw, yaw, yaw!"

"That is plain enough," said Nick sturdily "but if you mean to say that the answer to the problem I gave you is fifty per cent., you are wrong."

"Oxplains how dot ain't," said Mr. Ribsam, suddenly becoming serious.

The mother was also interested, and looked smilingly toward her bright son. Like every mother, her sympathies went out to him. When Nick told his father that he was in error, the mother felt a thrill of delight; she wanted Nick to get the better of her husband, much as she loved both, and you and I can't blame her.

Nick leaned back in his chair, shoved his hands into his pockets, and looked smilingly at his father and his pipe as he said:

"Suppose, to illustrate, that Philadelphia has just one hundred people. Then, if New York has fifty per cent. more, it must have one hundred and fifty people as its population; that is correct, is it not, father?"

Mr. Ribsam took another puff or two, as if to make sure that his boy was not leading him into a trap, and then he solemnly nodded his head.

"Dot ish so,—dot am,—yaw."

"Then if Philadelphia has one hundred people for its population, New York has one hundred and fifty?"

"Yaw, and Pheelatelphy has feefty per cent. less—yaw, yaw, yaw!"

"Hold on, father,—not so fast. I'm teacher just now, and you mustn't run ahead of me. If you will notice in this problem the per cent. in the first part is based on Philadelphia's population, while in the second part it is based on the population of New York, and since the population of the two cities is different, the per cent. cannot be the same."

"How dot is?" asked Mr. Ribsam, showing eager interest in the reasoning of the boy.

"We have agreed, to begin with, that the population of Philadelphia is one hundred and of New York one hundred and fifty. Now, how many people will have to be subtracted from New York's population to make it the same as Philadelphia?"

"Feefty,—vot I says."

"And fifty is what part of one hundred and fifty,—that is, what part of the population of New York?"

"It vos one thirds."

"And one third of anything is thirty-three and one third per cent. of it, which is the correct answer to the problem."

Mr. Ribsam held his pipe suspended in one hand while he stared with open mouth into the smiling face of his son, as though he did not quite grasp his reasoning.

"Vot you don't laughs at?" he said, turning sharply toward his wife, who had resumed her knitting and was dropping many a stitch because of the mirth, which shook her as vigorously as it stirred her husband a few minutes before.

"I laughs ven some folks dinks dey ain't shmarter don dey vosn't all te vile, don't it?"

And stopping her knitting she threw back her head and laughed unrestrainedly. Her husband hastily shoved the stem of his pipe between his lips, sunk lower down in the chair, and smoked so hard that his head soon became almost invisible in the vapor.

By-and-by he roused himself and asked Nick to begin with the first problem and reason out the result he obtained with each one in turn.

Nick did so, and on the last but one his parent tripped him. A few pointed questions showed the boy that he was wrong. Then the hearty "Yaw, yaw, yaw!" of the father rang out, and looking at the solemn visage of his wife, he asked:

"Vy you don't laughs now, eh? Yaw, yaw, yaw!"

The wife meekly answered that she did not see anything to cause mirth, though Nick proved that he did.

Not only that, but the son became satisfied from the quickness with which his father detected his error, and the keen reasoning he gave, that he purposely went wrong on the first problem read to him with the object of testing the youngster.

Finally, he asked him whether such was not the case. Many persons in the place of Mr. Ribsam would have been tempted to fib, because almost every one will admit any charge sooner than that of ignorance; but the Dutchman considered lying one of the meanest vices of

Comments (0)