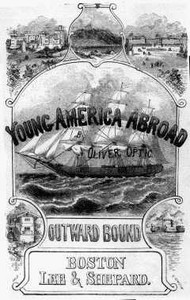

Outward Bound Or, Young America Afloat: A Story of Travel and Adventure, Optic [best non fiction books of all time txt] 📗

- Author: Optic

Book online «Outward Bound Or, Young America Afloat: A Story of Travel and Adventure, Optic [best non fiction books of all time txt] 📗». Author Optic

At ten o'clock the first part of the port watch was relieved, and the second part went on duty. Shuffles and Wilton were at liberty now, but there appeared to be a coldness between them, and Wilton sought another companion for his leisure hours. Sanborn and Adler belonged to his part of the watch, and he soon joined them.

"There isn't much difference between being off duty and being on," said Adler, as they seated themselves on the main hatch.

"There will be a difference when we have to make and take in sail every half hour. We had a big job taking in the studding sails last night."

"They don't drive the ship," added Sanborn. "I suppose if we were a merchantman, they would crack on all the sail she would carry."

"She goes along beautifully," said Wilton.

"She was only making five knots the last time the log was heaved."

"And the sea is as smooth as a mill-pond. We shall not get to Queenstown for two months at this rate."{182}

"Stand by to set studding sails!" shouted Pelham, the officer of the deck.

"I wondered why they didn't do that before," said Sanborn.

The fore and main studding sails were set, two at a time, by the part of the watch on duty, the wind still being well aft.

"What shall we do?" asked Wilton, with a long yawn, after they had watched the operation of setting the studding sails for a time. "This is stupid business, and I'm getting sleepy."

"Let us go below," suggested Sanborn.

"What for? The professors won't let you speak out loud while the recitations are going on," added Adler.

"We don't want to speak out loud. What do you say to shaking a little?" continued Wilton.

"I'm with you," replied Wilton. "Can either of you change me a half sovereign?"

Neither of them could, but they were willing to take Wilton's due bills, till his indebtedness amounted to ten shillings. The boys had already begun to talk the language of sterling currency, and many of them were supplied with English silver coins as well as gold. The three boys went down at the fore hatch, and removing their caps as they entered the steerage, walked silently to Gangway D, from which they went into mess room No. 8, which had thus far been the headquarters of the gamblers. Seating themselves on the stools, they used one of the beds as a table, and in a few moments were deeply absorbed in the exciting {183} game. They spoke in whispers, and were careful not to rattle the props too loudly.

After they had played a few moments, Shuffles came in. They invited him to join them in the play, but he declined, and soon left the mess room, returning to the deck. In the waist he met Paul Kendall, who was the officer of his watch, and, like him, was off duty. They had generally been on good terms while in the after cabin together, for then Shuffles was on his best behavior.

"How do things go on in the after cabin now, Kendall—I beg your pardon—Mr. Kendall?" said Shuffles, in his most gentlemanly tones.

"About as usual, Mr. Shuffles," replied Paul.

"I am not a 'mister' now," laughed Shuffles.

"Well, it's all the same to me. I am sorry you are not with us now."

"So am I," added Shuffles. "I did not expect to be on board this year, or I should have been there now."

"You can be, next term, if you like."

"This thing yesterday has ruined all my prospects."

"That was rather bad. I never was so sorry for anything in my life before," answered Paul, warmly. "You and I were always good friends after we got well acquainted, though I did vote for another at the election a year ago."

"You did what you thought was right, and I don't blame you for that. I always did my duty when I was an officer."

"That you did, Shuffles; and we always agreed first rate. Isn't it a little strange that I have not lived {184} in the steerage since the ship's company were organized?"

"That's because you were always a good boy, and a smart scholar. I think you would not like it."

"If it wasn't for losing my rank, I should like to try it," replied Paul. "I should like to get better acquainted with the fellows."

"You wouldn't like them in the steerage. You would see a great many things there which you never see in the cabin; a great many things which Mr. Lowington and the professors know nothing about."

"Why, what do you mean, Shuffles?" demanded Paul, astonished at this revelation.

"I ought not to say anything about it; but I believe these things will break up the Academy Ship one of these days, for the boys are growing worse instead of better in her, and their folks will find it out sooner or later."

"You surprise me!" exclaimed Paul, sadly, for he held the honor of the ship and her crew as the apple of his eye. "If there is anything wrong there, you ought to make it known."

"I suppose I ought; but you know I'm not a tell-tale."

"You have told me, and I'm an officer."

"Well, I blundered into saying what I have. What you said about going into the steerage made me let it out. I am sorry I said anything."

"You have raised my curiosity."

"I will tell you; or rather I will put you in the way of seeing for yourself, if you will not mention {185} my name in connection with the matter, even to Mr. Lowington, and certainly not to any one else."

"I will not, Shuffles."

"The fellows are gambling in the steerage at this very moment," added Shuffles, in a low tone. "Don't betray me."

"I will not. Gambling!" exclaimed Paul, with natural horror.

"You will find them in No. 8," continued Shuffles, walking away, and leaving the astonished officer to wonder how boys could gamble.

CHAPTER XII.{186}

THE ROOT OF ALL EVIL.Return to Table of Contents

Paul Kendall, who had not occupied a berth in the steerage since the first organization of the ship, was greatly surprised and grieved to learn that some of the crew were addicted to vicious practices. Gambling was an enormous offence, and he was not quite willing to believe that such a terrible evil had obtained a foothold in the ship. He could hardly conceive of such a thing as boys engaging in games of chance; only the vilest of men, in his estimation, would do so. Shuffles had told him so, apparently without malice or design, and there was no reason to doubt the truth of his statement, especially as he had given the particulars by which it could be verified.

The second lieutenant went down into the steerage. Classes were reciting to the professors, and studying their lessons at the mess tables. There was certainly no appearance of evil, for the place was still, and no sound of angry altercation or ribald jest, which his fancy connected with the vice of gambling, saluted his ears. He cautiously entered Gangway D, and paused where he could hear what was said in mess room No. 8.

"I'm five shillings into your half sovereign," said {187} one of the gamblers; and then Paul distinctly heard the rattling of the props.

"There's the half sovereign," added another, whose voice the officer recognized as that of Wilton. "You own five shillings in it, and I own five shillings."

"That's so," replied Sanborn, who appeared to be the lucky one.

"Let us shake for the coin," added Wilton. "It's my throw."

"That's rather steep."

"We get along faster—that's all. If I throw a nick, or a browner, it's mine; if an out, it's yours."

"I am agreed—throw away," replied Sanborn, without perceiving that the one who held the props had two chances to his one.

The props rattled, and dropped on the bed.

"A browner!" exclaimed Wilton, thereby winning all he had lost at one throw.

"Hush! don't talk so loud," interposed Adler. "You'll have the profs down upon us."

"I'll go you another five shillings on one throw," said Sanborn, chagrined at his loss.

"Put down your money."

The reckless young gambler put two half crowns, or five shillings, upon the bed, and Wilton shook again.

"A nick!" said he, seizing the two half crowns.

"Try it again," demanded Sanborn.

Paul Kendall was filled with horror as he listened to this conversation. When he had heard enough to satisfy him that the speakers were actually gambling, he hastened to inform Mr. Lowington of the fact. {188} Paul was an officer of the ship, and this was so plainly his duty that he could not avoid it, disagreeable as it was to give testimony against his shipmates. It seemed to him that the ship could not float much longer if such iniquity were carried on within her walls of wood; she must be purged of such enormities, or some fearful retribution would overtake her. There was no malice or revenge in the bosom of the second lieutenant; he was acting solely and unselfishly for the good of the institution and the students.

He went on deck again. Shuffles was still there, and they met in the waist.

"You told me the truth," said Paul.

"You did not think I was joking about so serious a matter—did you?" replied Shuffles.

"No; but I hoped you might be mistaken."

"How could I be mistaken, when I have seen, at one time and another, a dozen fellows engaged in gambling? Of course such things as these will ruin the boys, and bring the ship into disrepute."

"You are right. My father, for one, wouldn't let me stay on board a single day, if he knew any of the boys were gamblers."

"It can be easily stopped, now you know about it," added Shuffles.

"Perhaps it can. I will inform Mr. Lowington at once."

"Remember, if you please, what I said, Mr. Kendall. I am willing to do a good thing for the ship; but you know how much I should have to suffer, if it were known that I gave the information. I didn't mean to blow on my shipmates; but you and I have {189} been so intimate in the after cabin, that I spoke before I was aware what I was about," continued Shuffles.

"I shall not willingly betray you."

"Willingly! What do you mean by that?" demanded the conspirator, startled by the words of the officer.

"Suppose Mr. Lowington should ask me where I obtained my information," suggested Paul.

"Didn't you see for yourself in No. 8?"

"He might ask what led me to examine the matter so particularly. But, Shuffles, I will tell him honestly that I do not wish to inform him who gave me the hint; and I am quite sure he will not press the matter, when he finds that the facts are correct."

"Don't mention my name on any account," added Shuffles. "It was mean of me to say anything; but the ship was going to ruin, and I'm rather glad I spoke, though I didn't intend to do so."

"I will make it all right, Shuffles," replied Paul, as he descended the cabin steps.

Mr. Lowington was in the main cabin, and the second lieutenant knocked at the door. He was readily admitted, and invited to take a seat, for the principal was as polite to the young gentlemen as though they had been his equals in age and rank.

"I would like to speak with you alone, if you please, sir," Paul began, glancing at the cabin steward, who was at work in the pantry.

"Come into my state room," said the principal, leading the way.

"I hope your business does not relate to the discipline of the ship," continued Mr. Lowington, when {190} they were seated, and the door of the room was closed. "If it does, you should have applied to the captain."

"This is a peculiar case, sir, and I obtained my information while off duty," replied Paul, with some embarrassment; for he had thought of communicating his startling discovery to Captain Gordon, and had only been deterred from doing so by the fear of betraying Shuffles.

"I will hear what you have to say."

"There is something very bad going on in the steerage," said Paul, seriously.

"Indeed! What is it?" asked the principal, full of interest and anxiety.

"Gambling, sir."

"Gambling!" repeated Mr. Lowington, his brow contracting.

Paul made no reply; and he expected to be asked how he had obtained the startling information.

"Are you quite sure of what you say, Mr. Kendall?"

"Yes, sir, I am. In mess room No. 8, there are three or four students now engaged in gambling. I stood at the door long enough to find out what they were doing."

"This is serious, Mr. Kendall."

"If you have any doubt about the fact, sir, I hope you will take measures to satisfy yourself at once, for I think the students are still there."

"I will, Mr. Kendall; remain in this cabin, if you please, until my return," added

Comments (0)