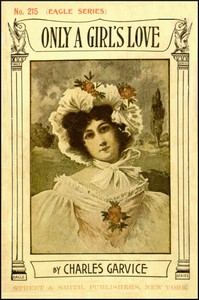

Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗». Author Charles Garvice

"Poor masters!" said Stella.

He laughed.

"Yes, they didn't have a particularly fine time of it when Leycester was at school."

As he spoke, he glanced at the tall figure of Lord Leycester in front of them with an admiring air such as a school-boy might wear.

"There isn't much that Leycester wouldn't dare," he said.

They entered the dining-room, a large room lined with oak and magnificently furnished, in which the long table with its snowy cloth, and glittering plate and glass, shone out conspicuously.

Lord Guildford found no difficulty in discovering their seats, each place being distinguished by a small tablet bearing the name of the intended occupant. As Stella took her seat, she noticed a beautiful bouquet beside her serviette, and saw that one was placed for every lady in the room.

A solemn, stately butler, who looked like a bishop, stood beside the earl's chair, and with a glance and a slight movement of his hand directed the noiseless footmen.

A clergyman said grace, and the dinner commenced. Stella, looking round, saw that her uncle was seated near Lady Wyndward, and that Lady Lenore was opposite herself. She looked round for Lord Leycester, and was startled to hear his voice at her left. He was speaking to Lady Longford. As she turned to look at him she happened to catch Lady Wyndward's eye also fixed upon him with a strange expression, and wondered what it meant; the next moment she knew, for, bending his head and looking straight before him, he said—

"Do you like your flowers?"

Stella took up the bouquet; it was composed almost entirely of white blossoms, and smelt divinely.

"They are beautiful," she said. "Heliotrope and camellias—my favorite flowers."

"It must have been instinct," he said.

"What do you mean?" she asked.

"I chose them," he said, in the same low voice.

"Chose them?" she retorted.

"Yes," and he smiled. "That was what made me late. I came in here first and had a grand review of the bouquets. I was curious to know if I could guess your favorite flowers."

"You—you—changed them!" said Stella, with a feeling of mild horror. "Lord Guildford asked me just now what I considered the most audacious act a man would commit. I know now."

[74]

He smiled.

"I changed something else," he said.

Stella looked at him inquiringly. There was a bold smile in his dark eyes.

He pointed to the little tablet bearing his name.

"This. I found it over the way there, next to that old lady in the emeralds. She is a dreadful old lady—beware of her. She is a politician, and she always asks everybody who comes near her what they think of the present Parliament. I thought it would be nicer to come over here."

The color crept slowly into Stella's face, and her eyes dropped.

"It was very wrong," she said. "I am sure Lady Wyndward will be angry. How could you interfere with the arrangements? They all seem so solemn and grand to me."

He laughed softly.

"They are. We always eat our meals as if they were the last we could expect to have—as if the executioner was waiting outside and feeling the edge of the ax impatiently. There is only one man here who dares to laugh outright."

"Who is that?" asked Stella.

He nodded to Lord Guildford, who was actively engaged in bending his head over his soup with the air of a hungry man. "Charlie," he said—"Lord Guildford, I mean. He laughs everywhere, don't you, Charlie?"

"Eh? Yes, oh, yes. What is he telling you about me, Miss Etheridge? Don't believe a word he says. I mean to have him up for libel some day."

"He says you laugh everywhere," said Stella.

Lord Charles laughed at once, and Stella looked round half alarmed, but nobody seemed to faint or show any particular horror.

"Nobody minds him," said Lord Leycester, balancing his spoon. "He is like the King's Jester, licensed to play wheresoever he pleases."

"I'm fearfully hungry," said Lord Charles. "I've been in the saddle since three o'clock—is that the menu, Miss Etheridge? Let us mark our favorite dishes," and he offered her a half-hold of the porcelain tablet on which was written the items of the various courses.

Stella looked down the long list with something like amused dismay.

"It's dreadfully long," she said. "I don't think I have any favorite dishes."

"No; not really!" he demanded. "What a treat! Will you really let me advise you?"

"I shall be most grateful," said Stella.

"Oh, this is charming," said Lord Guildford. "Next to choosing one's own dinner, there is nothing better than choosing one for someone else. Let me see;" and thereupon he made a careful selection, which Stella broke into with an amused laugh.

"I could not possibly eat all these things," she said.

"Oh, but you must," he said. "Why, I have been most careful to pick out only those dishes suitable for a lady's delicate[75] appetite; you can't leave one of them out, you can't, indeed, without spoiling your dinner."

"My dear," said the countess, bending forward, "don't let him teach you anything, except to take warning by his epicureanism; he is only anxious that you should be too occupied to disturb him."

Lord Charles laughed.

"That is cruel," he said. "You take my advice, Miss Etheridge; there are only two things I understand, and those are a horse and a good dinner."

Meanwhile the dinner was proceeding, and to Stella it seemed that "good" scarcely adequately described it. One elaborate course after another followed in slow succession, borne in by the richly-liveried footmen on the massive plate for which Wyndward Hall was famous. Dishes which she had never heard of seemed to make their appearance only to pass out again untouched, excepting by the clergyman, Lord Guildford, and one or two other gentlemen. She noticed that the earl scarcely touched anything beyond a tiny piece of fish and a mutton cutlet; and Lord Guildford, who seemed to take an interest in anything connected with the dinner, remarked, as he glanced at the stately head of the house—

"There is one other person present who is of your way of thinking, Miss Etheridge—I mean the earl. He doesn't know what a good dinner means. I don't suppose he will taste anything more than the fish and a piece of Cheshire. When he is in town and at work——"

"At work? said Stella.

"In the House of Lords, you know; he is a member of the Cabinet."

Stella nodded.

"He is a statesman?"

"Exactly. He generally dines off a mutton chop served in the library. I've seen him lunching off a penny biscuit and a glass of water. Terrible, isn't it?"

Stella laughed.

"Perhaps he finds he can work better on a chop and a glass of water," she said.

"Don't believe it!" retorted Lord Guildford. "No man can work well unless he is well-fed."

"Guildford ought to know," said Lord Leycester, audibly. "He does so much work."

"So I do," retorts Lord Charles. "Stay and keep you in order, and if that isn't hard work I don't know what is!"

This was very amusing for Stella; it was all so strange, too, and so little what she imagined; here were two peers talking like school-boys for her amusement, as if they were mere nobodies and she were somebody worth amusing.

Every now and then she could hear Lady Lenore's voice, musical and soft, yet full and distinct; she was talking of the coming season, and Stella heard her speak of great people—persons' names which she had read of, but never expected to hear spoken of so familiarly. It seemed to her that she had got into some[76] charmed circle; it scarcely seemed real. Then occasionally, but very seldom, the earl's thin, clear, high-bred voice would be heard, and once he looked across at Stella herself, and said:

"Will you not try some of those rissoles, Miss Etheridge? They are generally very good."

"And he never touches them," murmured Lord Charles, with a mock groan.

She could hear her uncle talking also—talking more fluently than was his wont—to Lady Wyndward, who was speaking about the pictures, and once Stella saw her glance in her direction as if they had been speaking of her. The dinner seemed very long, but it came to an end at last, and the countess rose. As Stella rose with the rest of the ladies, the old Countess of Longford locked her arm in hers.

"I am not so old that I can't walk, and I am not lame, my dear," she said, "but I like something young and strong to lean upon; you are both. You don't mind?"

"No!" said Stella. "Yes, I am strong."

The old countess looked up at her with a glance of admiration in her gray eyes.

"And young," she said significantly.

They passed into a drawing-room—not the one they had entered first, but a smaller room which bore the name of "my lady's." It was exquisitely furnished in the modern antique style. There were some beautiful hangings that covered the walls, and served as background for costly cabinets and brackets, upon which was arranged a collection of ancient china second to none in the kingdom. The end of the room opened into a fernery, in which were growing tall palms and whole miniature forests of maidenhair, kept moist by sparkling fountains that fell with a plash, plash, into marble basins. Birds were twitting and flitting about behind a wire netting, so slight and carefully concealed as to be scarcely perceptible.

No footman was allowed to enter this ladies' paradise; two maids, in their soft black dresses and snowy caps, were moving about arranging a table for the countess to serve tea upon.

It was like a scene from the "Arabian Nights," only more beautiful and luxurious than anything Stella had imagined even when reading that wonderful book of fairy-tales.

The countess went straight to her table and took off her gray-white gloves, some of the ladies settled themselves in the most indolent of attitudes on the couches and chairs, and others strolled into the fern house. The old countess made herself comfortable on a low divan, and made room for Stella beside her.

"And this is your first visit to Wyndward Hall, my dear?" she said.

"Yes," answered Stella, her eyes still wandering round the room.

"And you live in that little village on the other side of the river?"

"Yes," said Stella, again. "It is very pretty, is it not?"

[77]

"It is, as pretty as anything in one of your uncle's pictures. And are you quite happy?"

Stella brought her eyes upon the pale, wrinkled face.

"Happy! Oh, yes, quite," she said.

"Yes, I think you are," said the old lady with a keen glance at the beautiful face and bright, pure eyes. "Then you must keep so, my dear," she said.

"But isn't that rather difficult?" said Stella, with a smile.

Lady Longford looked at her.

"That serves me right for meddling," she said. "Yes, it is difficult, very difficult, and yet the art is easy enough; it contains only one rule, and that is 'to be content.'"

"Then I shall continue to be happy," said Stella; "for I am very content."

"For the present," said the old lady. "Take care, my dear!"

Stella smiled; it was a strange sort of conversation, and there was a suggestion of something that did not appear on the surface.

"Do you think that I look very discontented, then?" she asked.

"No," said the old lady, eying her again. "No, you look very contented—at present. Isn't that a beautiful forest?"

It was an abrupt change of the subject, but Stella was equal to it.

"I have been admiring it since I came in," she said; "it is like fairy land."

"Go and enter it," said the old countess—"I am going to sleep for exactly ten minutes. Will you come back to me then? You see, I am very frank and rude; but I am very old indeed."

Stella rose with a smile.

"I think you are very kind to me," she said.

The old countess looked up at the beautiful face with the dark, soft eyes bent down on her; and something like a sigh of regret came into her old, keen eyes.

"You know how to make pretty speeches, my dear," she said. "You learnt that in Italy, I expect. Mind you come back to me."

Then, as Stella moved away, the old lady looked after her.

"Poor child!" she murmured—"poor child! she is but a child; but he won't care. Is it too late, I wonder? But why should I worry about it?"

But it seemed as if she must worry about it, whatever it was, for after a few minutes' effort to sleep, she rose and

Comments (0)