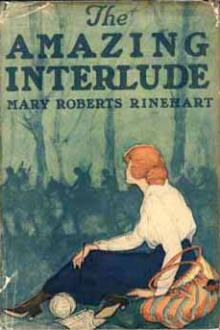

The Amazing Interlude, Mary Roberts Rinehart [diy ebook reader TXT] 📗

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Book online «The Amazing Interlude, Mary Roberts Rinehart [diy ebook reader TXT] 📗». Author Mary Roberts Rinehart

A week. Two weeks. Twice the village was bombarded severely, but the little house escaped by a miracle. Marie considered it the same miracle that left holy pictures unhurt on the walls of destroyed houses, and allowed the frailest of old ebony and rosewood crucifixes to remain unharmed.

Great generals, often as tall as they were great, stopped at the little house to implore Sara Lee to leave. But she only shook her head.

"Not unless you send me away," she always said; "and that would break my heart."

"But to move, mademoiselle, only to the next village!" they would remonstrate, and as a final argument: "You are too valuable to risk an injury."

"I must remain here," she said. And some of them thought they understood. When an unusually obdurate officer came along, Sara Lee would insist on taking him to the cellar.

"You see!" she would say, holding her candle high. "It is a nice cellar, warm and dry. It is"—proudly—"one of the best cellars in the village. It is a really homelike cellar."

The officer would go away then, and send her cigarettes for her men or, as in more than one case, a squad with bags of earth and other things to protect the little house as much as possible. After a time the little house began to represent the ideas in protection and camouflage, then in its early stages, of many different minds.

René shot a man there one night, a skulking figure working its way in the shadows up the street. It was just before dawn, and René, who was sleepless those days, like the others, called to him. The man started to run, dodging behind walls. But René ran faster and killed him.

He was a German in Belgian peasant's clothing. But he wore the great shoes of the German soldier, and he had been making a rough map of the Belgian trenches.

Sara Lee did not see him. But when she heard the shot she went out, and René told her breathlessly.

From that time on her terrors took the definite form of Henri lying dead in a ruined street, and being buried, as this man was buried, without ceremony and without a prayer, in some sodden spring field.

XVIII

As the spring advanced Harvey grew increasingly bitter; grew morbid and increasingly self-conscious also. He began to think that people were smiling behind his back, and when they asked about Sara Lee he met with almost insulting brevity what he felt was half-contemptuous kindness. He went nowhere, and worked all day and until late in the night. He did well in his business, however, and late in March he received a substantial raise in salary. He took it without enthusiasm, and told Belle that night at dinner with apathy.

After the evening meal it was now his custom to go to his room and there, shut in, to read. He read no books on the war, and even the quarter column entitled Salient Points of the Day's War News hardly received a glance from him now.

In the office when the talk turned to the war, as it did almost hourly, he would go out or scowl over his letters.

"Harvey's hit hard," they said there.

"He's acting like a rotten cub," was likely to be the next sentence. But sometimes it was: "Well, what'd you expect? Everything ready to get married, and the girl beating it for France without notice! I'd be sore myself."

On the day of the raise in salary his sister got the children to bed and straightened up the litter of small garments that seemed always to bestrew the house, even to the lower floor. Then she went into Harvey's room. Coat and collar off, he was lying on the bed, but not reading. His book lay beside him, and with his arms under his head he was staring at the ceiling.

She did not sit down beside him on the bed. They were an undemonstrative family, and such endearments as Belle used were lavished on her children. But her eyes were kind, and a little nervous.

"Do you mind talking a little, Harvey?"

"I don't feel like talking much. I'm tired, I guess. But go on. What is it? Bills?"

She came to him in her constant financial anxieties, and always he was ready to help her out. But his tone now was gruff. A slight flush of resentment colored her cheeks.

"Not this time, Harve. I was just thinking about things."

"Sit down."

She sat on the straight chair beside the bed, the chair on which, in neat order, Harvey placed his clothing at night, his shoes beneath, his coat over the back.

"I wish you'd go out more, Harvey."

"Why? Go out and talk to a lot of driveling fools who don't care for me any more than I do for them?"

"That's not like you, Harve."

"Sorry." His tone softened. "I don't care much about going round, Belle. That's all. I guess you know why."

That Henri might be living, somewhere--that some day the Belgians might go home again.

"So does everybody else."

He sat up and looked at her.

"Well, suppose they do? I can't help that, can I? When a fellow has been jilted—"

"You haven't been jilted."

He lay down again, his arms under his head; and Belle knew that his eyes were on Sara Lee's picture on his dresser.

"It amounts to the same thing."

"Harvey," Belle said hesitatingly, "I've brought Sara Lee's report from the Ladies' Aid. May I read it to you?"

"I don't want to hear it." Then: "Give it here. I'll look at it."

He read it carefully, his hands rather unsteady. So many men given soup, so many given chocolate. So many dressings done. And at the bottom Sara Lee's request for more money—an apologetic, rather breathless request, and closing, rather primly with this:

"I am sure that the society will feel, from the above report, that the work is worth while, and worth continuing. I am only sorry that I cannot send photographs of the men who come for aid, but as they come at night it is impossible. I enclose, however, a small picture of the house, which is now known as the little house of mercy."

"At night!" said Harvey. "So she's there alone with a lot of ignorant foreigners at night. Why the devil don't they come in the daytime?"

"Here's the picture, Harvey."

He got up then, and carried the tiny photograph over close to the gas jet. There he stood for a long time, gazing at it. There was René with his rifle and his smile. There was Marie in her white apron. And in the center, the wind blowing her soft hair, was Sara Lee.

Harvey groaned and Belle came over and putting her hand on his shoulder looked at the photograph with him.

"Do you know what I think, Harvey?" she said. "I think Sara Lee is right and you are wrong."

He turned on her almost savagely.

"That's not the point!" he snapped out. "I don't begrudge the poor devils their soup. What I feel is this: If she'd cared a tinker's damn for me she'd never have gone. That's all."

He returned to a moody survey of the picture.

"Look at it!" he said. "She insists that she's safe. But that fellow's got a gun. What for, if she's so safe? And look at that house! There's a corner shot away; and it's got no upper floor. Safe!"

Belle held out her hand.

"I must return the picture to the society, Harve."

"Not just yet," he said ominously. "I want to look at it. I haven't got it all yet. And I'll return it myself—with a short speech."

"Harvey!"

"Well," he retorted, "why shouldn't I tell that lot of old scandalmongers what I think of them? They'll sit here safe at home and beg money—God, one of them was in the office to-day!—and send a young girl over to—You'd better get out, Belle. I'm not company for any one to-night."

She turned away, but he came after her, and suddenly putting his arms round her he kissed her.

"Don't worry about me," he said. "I'm done with wearing my heart on my sleeve. She looks happy, so I guess I can be." He released her. "Good night. I'll return the picture."

He sat up very late, alternately reading the report and looking at the picture. It was unfortunate that Sara Lee had smiled into the camera. Coupled with her blowing hair it had given her a light-heartedness, a sort of joyousness, that hurt him to the soul.

He made some mad plans after he had turned out the lights—to flirt wildly with the unattached girls he knew; to go to France and confront Sara Lee and then bring her home. Or—He had found a way. He lay there and thought it over, and it bore the test of the broken sleep that followed. In the morning, dressing, he wondered he had not thought of it before. He was more cheerful at breakfast than he had been for weeks.

XIX

In the little house of mercy two weeks went by, and then a third. Soldiers marching out to the trenches sometimes wore flowers tucked gayly in their caps. More and more Allied aëroplanes were in the air. Sometimes, standing in the streets, Sara Lee saw one far overhead, while balloon-shaped clouds of bursting shells hung far below it.

Once or twice in the early morning a German plane, flying so low that one could easily see the black cross on each wing, reconnoitered the village for wagon trains or troops. Always they found it empty.

Hope had almost fled now. In the afternoons Marie went to the ruined church, and there knelt before the heap of marble and masonry that had once been the altar, and prayed. And Sara Lee, who had been brought up a Protestant and had never before entered a Catholic church, took to going there too. In some strange fashion the peace of former days seemed to cling to the little structure, roofless as it was. On quiet days its silence was deeper than elsewhere. On days of much firing the sound from within its broken walls seemed deadened, far away.

Marie burned a candle as she prayed, for that soul in purgatory which she had once loved, and now pitied. Sara Lee burned no candle, but she knelt, sometimes beside Marie, sometimes alone, and prayed for many things: that Henri should be living, somewhere; that the war might end; that that day there would be little wounding; that some day the Belgians might go home again; and that back in America Harvey might grow to understand and forgive her. And now and then she looked into the very depths of her soul, and on those days she prayed that her homeland might, before it was too late, see this thing as she was seeing it. The wanton waste of it all, the ghastly cruelty the Germans had brought into this war.

Sara Lee's vague thinking began to crystallize. This war was not a judgment sent from on high to a sinful world. It was the wicked imposition of one nation on other nations. It was national. It was almost racial. But most of all it was a war of hate on the German side. She had never believed in hate. There were ugly passions in the world—jealousy, envy, suspicion; but not hate. The word was not in her rather limited vocabulary.

There was no hate on the part of the men she knew. The officers who stopped in on their way to and from the trenches were gentlemen and soldiers. They were determined and grave; they resented, they even loathed. But they did not hate. The little Belgian soldiers were bewildered, puzzled, desperately resentful. But of hate, as translated into terms of frightfulness, they had no understanding.

Yet from the other side were coming methods of war so wantonly cruel, so useless save as inflicting needless

Comments (0)