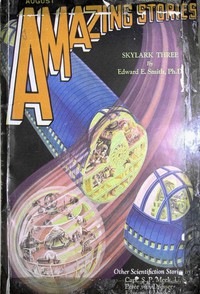

Skylark Three, E. E. Smith [libby ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: E. E. Smith

Book online «Skylark Three, E. E. Smith [libby ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author E. E. Smith

"You can do a lot if you will. Put on that headset again and get my plan, offering any suggestions your far abler brain may suggest."

As the human scientist poured his plan of battle into the brain of the astronomer, Orlon's face cleared.

"It is graven upon the Sphere that the Fenachrone shall pass," he said finally. "What you ask of us we can do. I have only a general knowledge of rays, as they are not in the province of the Orlon family; but the student Rovol, of the family Rovol of Rays, has all present knowledge of such phenomena. Tomorrow I will bring you together, and I have little doubt that he will be able, with the help of your metal of power, to solve your problem."

"I don't quite understand what you said about a whole family studying one subject, and yet having only one student in it," said Dorothy, in perplexity.

"A little explanation is perhaps necessary," replied Orlon. "First, you must know that every man of Norlamin is a student, and most of us are students of science. With us, 'labor' means mental effort, that is, study. We perform no physical or manual labor save for exercise, as all our mechanical work is done by forces. This state of things having endured for many thousands of years, it long ago became evident that specialization was necessary in order to avoid duplication of effort and to insure complete coverage of the field. Soon afterward, it was discovered that very little progress was being made in any branch, because so much was known that it took practically a lifetime to review that which had already been accomplished, even in a narrow and highly specialized field. Many points were studied for years before it was discovered that the identical work had been done before, and either forgotten or overlooked. To remedy this condition the mechanical educator had to be developed. Once it was perfected a new system was begun. One man was assigned to each small subdivision of scientific endeavor, to study it intensively. When he became old, each man chose a successor—usually a son—and transferred his own knowledge to the younger student. He also made a complete record of his own brain, in much the same way as you have recorded the brain of the Fenachrone upon your metallic tape. These records are all stored in a great central library, as permanent references.

"All these things being true, now a young person may need only finish an elementary education—just enough to learn to think, which takes only about twenty-five or thirty years—and then he is ready to begin actual work. When that time comes, he receives in one day all the knowledge of his specialty which has been accumulated by his predecessors during many thousands of years of intensive study."

"Whew!" Seaton whistled, "no wonder you folks know something! With that start, I believe I might know something myself! As an astronomer, you may be interested in this star-chart and stuff—or do you know all about that already?"

"No, the Fenachrone are far ahead of us in that subject, because of their observatories out in open space and because of their gigantic reflectors, which cannot be used through any atmosphere. We are further hampered in having darkness for only a few hours at a time and only in the winter, when our planet is outside the orbit of our sun around the great central sun of our entire system. However, with the Rovolon you have brought us, we shall have real observatories far out in space; and for that I personally will be indebted to you more than I can ever express. As for the chart, I hope to have the pleasure of examining it while you are conferring with Rovol of Rays."

"How many families are working on rays—just one?"

"One upon each kind of ray. That is, each of the ray families knows a great deal about all kinds of vibrations of the ether, but is specializing upon one narrow field. Take, for instance, the rays you are most interested in; those able to penetrate a zone of force. From my own very slight and general knowledge I know that it would of necessity be a ray of the fifth order. These rays are very new—they have been under investigation only a few hundred years—and the Rovol is the only student who would be at all well informed upon them. Shall I explain the orders of rays more fully than I did by means of the educator?"

"Please. You assumed that we knew more than we do, so a little explanation would help."

"All ordinary vibrations—that is, all molecular and material ones, such as light, heat, electricity, radio, and the like—were arbitrarily called waves of the first order; in order to distinguish them from waves of the second order, which are given off by particles of the second order, which you know as protons and electrons, in their combination to form atoms. Your scientist Millikan discovered these rays for you, and in your language they are known as Millikan, or Cosmic, rays.

"Some time later, when sub-electrons were identified the rays given off by their combination into electrons, or by the disruption of electrons, were called rays of the third order. These rays are most interesting and most useful; in fact, they do all our mechanical work. They as a class are called protelectricity, and bear the same relation to ordinary electricity that electricity does to torque—both are pure energy, and they are inter-convertible. Unlike electricity, however, it may be converted into many different forms by fields of force, in a[Pg 559] way comparable to that in which white light is resolved into colors by a prism—or rather, more like the way alternating current is changed to direct current by a motor-generator set, with attendant changes in properties. There is a complete spectrum of more than five hundred factors, each as different from the others as red is different from green.

"Continuing farther, particles of the fourth order give rays of the fourth order; those of the fifth, rays of the fifth order. Fourth-order rays have been investigated quite thoroughly, but only mathematically and theoretically, as they are of excessively short wave-length and are capable of being generated only by the breaking down of matter itself into the corresponding particles. However, it has been shown that they are quite similar to protelectricity in their general behavior. Thus, the power that propels your space-vessel, your attractors, your repellers, your object-compass, your zone of force—all these things are simply a few of the many hundreds of wave-bands of the fourth order, all of which you doubtless would have worked out for yourselves in time. Very little is known, even in theory, of the rays of the fifth order, although they have been shown to exist."

"For a man having no knowledge, you seem to know a lot about rays. How about the fifth order—is that as far as they go?"

"My knowledge is slight and very general; only such as I must have in order to understand my own subject. The fifth order certainly is not the end—it is probably scarcely a beginning. We think now that the orders extend to infinite smallness, just as the galaxies are grouped into larger aggregations, which are probably in their turn only tiny units in a scheme infinitely large.

"Over six thousand years ago the last third order rays were worked out; and certain peculiarities in their behavior led the then Rovol to suspect the existence of the fourth order. Successive generations of the Rovol proved their existence, determined the conditions of their liberation, and found that this metal of power was the only catalyst able to decompose matter and thus liberate the rays. This metal, which was called Rovolon after the Rovol, was first described upon theoretical grounds and later was found, by spectroscopy, in certain stars, notably in one star only eight light-years away, but not even the most infinitesimal trace of it exists in our entire solar system. Since these discoveries, the many Rovol have been perfecting the theory of the fourth order, beginning that of the fifth, and waiting for your coming. The present Rovol, like myself and many others whose work is almost at a standstill, is waiting with all-consuming interest to greet you, as soon as the Skylark can be landed upon our planet."

"Neither your rocket-ships nor your projections could get you any Rovolon?"

"No. Every hundred years or so someone develops a new type of rocket that he thinks may stand a slight chance of making the journey, but not one of these venturesome youths has as yet returned. Either that sun has no planets or else the rocket-ships have failed. Our projections are useless, as they can be driven only a very short distance upon our present carrier wave. With a carrier of the fifth order we could drive a projection to any point in the galaxy, since its velocity would be millions of times that of light and the power necessary reduced accordingly—but as I have said before, such waves cannot be generated without metal Rovolon."

"I hate to break this up—I'd like to listen to you talk for a week—but we're going to land pretty quick, and it looks as though we were going to land pretty hard."

"We will land soon, but not hard," replied Orlon confidently, and the landing was as he had foretold. The Skylark was falling with an ever-decreasing velocity, but so fast was the descent that it seemed to the watchers as though they must crash through the roof of the huge brilliantly lighted building upon which they were dropping and bury themselves many feet in the ground beneath it. But they did not strike the observatory. So incredibly accurate were the calculations of the Norlaminian astronomer and so inhumanly precise were the controls he had set upon their bar, that, as they touched the ground after barely clearing the domed roof and he shut off their power, the passengers felt only a sudden decrease in acceleration, like that following the coming to rest of a rapidly moving elevator, after it has completed a downward journey.

"I shall join you in person very shortly," Orlon said, and the projection vanished.

"Well, we're here, folks, on another new world. Not quite as thrilling as the first one was, is it?" and Seaton stepped toward the door.

"How about the air composition, density, gravity, temperature, and so on?" asked Crane. "Perhaps we should make a few tests."

"Didn't you get that on the educator? Thought you did. Gravity a little less than seven-tenths. Air composition, same as Osnome and Dasor. Pressure, half-way between Earth and Osnome. Temperature, like Osnome most of the time, but fairly comfortable in the winter. Snow now at the poles, but this observatory is only ten degrees from the equator. They don't wear clothes enough to flag a hand-car with here, either, except when they have to. Let's go!"

He opened the door and the four travelers stepped out upon a close-cropped lawn—a turf whose blue-green softness would shame an Oriental rug. The landscape was illuminated by a soft and mellow, yet intense green light which emanated from no visible source. As they paused and glanced about them, they saw that the Skylark had alighted in the exact center of a circular enclosure a hundred yards in diameter, walled by row upon row of shrubbery, statuary, and fountains, all bathed in ever-changing billows of light. At only one point was the circle broken. There the walls did not come together, but continued on to border a lane leading up to the massive structure of cream-and-green marble, topped by its enormous, glassy dome—the observatory of Orlon.

"Welcome to Norlamin, Terrestrials," the deep, calm voice of the astronomer greeted them, and Orlon in the flesh shook hands cordially in the American fashion with each of them in turn, and placed around each neck a crystal chain from which depended a small Norlaminian chronometer-radiophone. Behind him there stood four other old men.

"These men are already acquainted with each of you, but you do not as yet know them. I present Fodan, Chief of the Five of Norlamin. Rovol, about whom you know. Astron, the First of Energy. Satrazon, the First of Chemistry."

Orlon fell in beside Seaton and the party turned toward the observatory. As they walked along the Earth-people stared, held by the unearthly beauty of the[Pg 560] grounds. The hedge of shrubbery, from ten to twenty feet high, and which shut out all sight of everything outside it, was one mass of vivid green and flaring crimson leaves; each leaf and twig groomed meticulously into its precise place in a fantastic geometrical scheme. Just inside this boundary there stood a ring of statues of heroic size. Some of them were single figures of men and women; some were busts; some were groups in natural or allegorical poses—all were done with consummate skill and feeling. Between the statues there were fountains, magnificent bronze and glass groups of the strange aquatic denizens of this strange planet, bathed in geometrically shaped sprays, screens, and columns of water. Winding around between the statues and the fountains there was a moving, scintillating wall, and upon the waters and upon the wall there played torrents of color, cataracts

Comments (0)