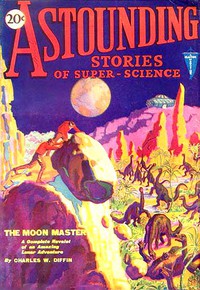

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930, Various [best novels to read txt] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930, Various [best novels to read txt] 📗». Author Various

From time to time the two stopped to catch better the direction of the wails. At last, they located the spot where the injured person lay.

It was under a great bombax tree, and on the shaded ground writhed a man. The two stopped, horrified at the squirming figure. The man was tearing at his face with his nails, and his countenance was bloody with long scratches.

He cursed and moaned in Spanish, and Durkin, approaching closer, recognized Juan the peon.

"Hey, Juan, what the hell's the matter? A snake bite you?"

The bronzed face of the sturdy little peon writhed in agony. He screamed in answer, he could not talk coherently. He mumbled, he groaned, but they could not catch his words.

At his side lay a small lead container, and closer, as though he had dropped it after extracting it from its case, lay a tube some six inches in length. It[372] was a queer tube, for it seemed to be filled with smoky, pallid worms of light that writhed even as Juan writhed.

"What's the trouble?" asked Durkin gruffly, for he was alarmed at the behavior of the peon. It seemed to both tramps that the man must have gone mad.

hey kept back from him, with ready guns. Juan shrieked, and it sounded as though he said he was burning up, in a great fire.

Suddenly the peon staggered to his feet; as he pushed himself up, his hands gripped the tube, and he clawed at his face.

Perplexity and horror were writ on the faces of the two tramps. Maget was struck with pity for the unfortunate peon, who seemed to be suffering the tortures of the damned. He was not a bad man, was Maget, but rather a weakling who had a run of bad luck and was under the thumb of Durkin, a really hard character. Durkin, while astounded at the actions of Juan, showed no pity.

Maget stepped forward, to try and comfort Juan; the peon struck out at him, and whirled around. But a few yards away was the bank of the stream, and Juan crashed into a black palm set with spines, caromed off it, and fell face downward into the water. The glass tube was smashed and the pieces fell into the stream.

"God, he must be blind," groaned Maget. "Poor guy, I've got to save him."

"The hell with him," growled Durkin. He grasped his partner's arm and stared curiously down at the dying peon.

"Let go, I'll pull him out," said Maget, trying to wrench away from Durkin.

"He's done for. Why worry about a peon?" said Durkin. "Look at those fish!"

The muddy waters of the stream had parted, and dead fish were rising about the body of Juan. But not about the dying man so much as close to the spot where the broken tube had fallen. White bellies up, the fish died as though by magic.

"Let's—let's get the hell back to Manoas, Bill," said Maget in a sickly voice. "This—this is too much for me."

nameless fear, which had been with Maget ever since the beginning of the venture, was growing more insistent.

"What?" cried Durkin. "Turn back now? The hell you say! That damn peon got into a fight with somebody and maybe got bit by a snake later. We'll go on and get that treasure."

"But—but what made those fish come up that way?" said Maget, his brows creased in perplexity.

Durkin shrugged. "What's the difference? We're O. K., ain't we?"

In spite of the stout man's bravado, it was evident that he, too, was disturbed at the strange happenings. He kept voicing aloud the question in his mind; what was in the queer tube?

But he forced Maget to go on. Without Juan, the peon, to leave them caches of food on the trail, they would have a difficult time getting provender, but both were trained jungle travelers and could find fruit and shoot enough game to keep them going.

Day after day they marched on, not far from the rear of the party before them. They took care to keep off Gurlone's heels, for they did not wish their presence to be discovered.

When they had been on the journey, which led them east, for four days, the two rascals came to a waterless plateau, which stretched before them in dry perspective. Before they came to the end of this, they knew what real thirst was, and their tongues were black in their mouths before they caught the curling smoke of fires in the valley where they knew the mine must be.

"That's the mine," gasped Durkin, pointing to the smoke.[373]

he sun was setting in golden splendor at their backs; they crept forward, using great boulders and piles of reddish earth, strange to them, for cover. Finally they reached the trail which led to the hills overlooking the valley, and a panorama spread before them which amazed them because of its elaborateness.

It seemed more like a stage scene than a wilderness picture. Straight ahead of them, as they lay flat on their stomachs and peered at the big camp, yawned the black mouth of a large cavern. This, they were sure, was the mine itself. Close by this mouth stood a stone hut. It was clear that this building had something to do with the ore, perhaps a refining plant, Durkin suggested.

There were long barracks for the peons, inside a barbed wire enclosure, and they could see the little men lounging now about campfires, where frying food was being prepared. Also, there was a long, low building with many windows in it, and houses for supplies and for the use of the owners of the camp.

"Looks like they were ready in case of a fight," said Durkin at last. "That fence around the peons looks like they might be havin' trouble."

"Some camp," breathed Maget.

"We got to find somethin' to drink," said Durkin. "Come on."

They worked their way about the rim of the valley, and in doing so caught glimpses of Professor Gurlone, the elderly man they had spotted in Manaos, and also saw the big Portuguese with his sightless eyes.

At the other side of the valley, they came on a spring which flowed to the east and disappeared under ground farther down.

"Funny water, ain't it?" said Durkin, lying down on his stomach to suck up the milky water.

But they were not in any mood to be particular about the fluids they drank. The long dry march across the arid lands separating the camp from the rest of the world had taken all moisture from their throats.

aget, drinking beside his partner, saw that the water glinted and sparkled, though the sun was below the opposite rim of the valley. It seemed that greenish, silvery specks danced in the milky fluid.

"Boy, that's good," Durkin finally found time to say, "I feel like I could fight a wildcat."

The water did, indeed, impart a feeling of exhilaration to the two tramps. They crept up close to the roof of the parallel shaft which they had seen from the other side of the valley, and looked down into the camp again.

Professor Gurlone of the livid face and Espinosa the blind Portuguese, were talking to a big man whose golden beard shone in the last rays of the sun.

"That's the old bird's son," said Durkin, "that Juan told us about. Young Gurlone."

A rumbling, pleasant laugh floated on the breeze, issuing from the big youth's throat. The wind was their way, now, and the valley breathed forth an unpleasant odor of chemicals and tainted meat.

"Funny place," said Maget. "Say, I got a hell of a headache, Bill."

"So've I," grunted Durkin. "Maybe that water ain't as good as it seemed at first."

hey lay in a small hollow, watching the activity of the camp. The peons were in their pen, and it was evident that they were being watched by the owners of the camp.

As purple twilight fell across the strange land, the two tramps began to notice the dull sounds which came to their ears from time to time.

"That's funny thunder," said Maget nervously. "If I didn't know it was thunder, I'd swear some big frogs were around here."

"Oh, hell. Maybe it's an earthquake," said Durkin irritatedly. "For God's sake, quit your bellyachin'. You've[374] done nothin' but whine ever since we left Juan."

"Well, who could blame me—" began Maget. He broke off suddenly, the pique in his voice turned to a quiver of fear, as he grasped Durkin's arm. "Oh, look," he gasped.

Durkin, seeing his partner's eyes staring at a point directly behind him, leaped up and scrambled away, thinking that a snake must be about to strike him.

He turned round when he felt he was far enough away, and saw that the ground was moving near the spot where he had been lying.

The earth was heaving, as though ploughed by a giant share; a blunt, purplish head, which seemed too fearful to be really alive, showed through the broken ground, and a worm began to draw its purple length from the depths. It was no snake, but a gigantic angleworm, and as it came forth, foot after foot, the two watched with glazed eyes.

Maget swallowed. "I've seen 'em two feet long," he said. "But never like that."

Durkin, however, when he realized that the loathsome creature could not see them and was creeping blindly towards them with its ugly, fat body creasing and elongating, picked up rocks and began to destroy the monstrous worm. He cursed as he worked.

Dull red blood spattered them, and a fetid odor from the gashes caused them to retch, but they finally cut the thing in two, and then they moved away from there.

he dull rumblings beneath them frightened Maget, and Durkin too, though the latter tried to brazen it out.

"Come on, it's gettin' dark. We can take a look in their mine now."

Maget, whimpering, followed. The booming sounds were increasing.

But Durkin slipped down the hillside, and Maget followed into the valley. They crept past the stone shack, which they noticed was padlocked heavily.

Durkin stopped suddenly, and cursed. "I've cut my foot," he said. "These damn shoes are gone, all right, from that march. But come on, never mind."

They crept to the mouth of the cavern and peered in. "Ugh," said Maget.

He drew back with a shudder. The floor of the mine was covered with a grey slush, in which were seething white masses of slugs weaving in the slime. A powerful, rotten odor breathed in their faces, as though they stood in the mouth of a great giant.

"Ah!" yelled Durkin, throwing his arms across his face.

The greenish, ghostly light which emanated from the slime was weaker than moonlight, just enough to see by; a vast shadow hovered above their heads, as though a gigantic bat flew there. The sweep and beat of great wings drove them back, and they fled in terror from such awful corruption.

But the flying monster, with a wing spread of eight feet, dashed past them, and silhouetted against the rising moon like a goblin. Then came another, and finally a flock of the big birds.

Durkin and Maget ran away, passing the stone house which stood near the cavern's mouth. The booming sounds from the bowels of the earth filled their ears now, and it was not thunder; no, it issued from the depths of the mine.

"We—we got to get somethin' to eat," said Durkin, as they paused near one of the shacks, in which shone a light.

ounds of voices came from the interior. They crept closer, and listened outside the window. Inside, they could see Espinosa, Gurlone senior, and the big youth with the golden beard, Gurlone junior.

"Yes, father," the young man was saying. "I believe we had better leave, at once. It's getting dangerous. I've reached the five million mark now, with the new process, and it is ready to[375] work with or sell, just as we wish."

"Hear that?" whispered Durkin triumphantly. "Five million!"

"It's all ready, in the stone house," said young Gurlone.

"Why should we leave now?" said old Gurlone, his livid face working. "Now, when we are just at the point of success in our great experiments? So far, while we have struck many creatures of abnormal growth, still, we have overcome them."

"Well, father, there is something in the mine now

Comments (0)