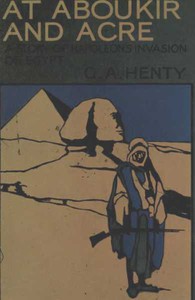

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt, G. A. Henty [top 10 inspirational books .txt] 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

Book online «At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt, G. A. Henty [top 10 inspirational books .txt] 📗». Author G. A. Henty

"I quite understand, Mr. Blagrove, that although you are given a midshipman's rating, it is really as an interpreter that Sir Sidney Smith has engaged you. Would you wish to perform midshipman's duties also? I have asked him what are his wishes in the matter, and he left it entirely with you, saying that the very nominal pay of a midshipman was really no remuneration for the services of a gentleman capable of interpreting in three or four languages, but that as the rules of the service made no provision for the engagement of an interpreter, except under special circumstances, and as you said that you did not think it likely you should make the sea your profession, you might not care to undertake midshipman's duties in addition to those of interpreter."

"Thank you, sir; but I should certainly wish to learn my duties as midshipman, and to take my share in all work. My duties as interpreter must be generally very light, and I should find the time hang heavily on my hands if I[Pg 174] had nothing else to do. I hope, therefore, sir, that you will put me to work, and have me taught my duty just as if I had joined in the regular way."

"Very well, Mr. Blagrove, I think that you are right. I will put you in the starboard watch. I am sure that Mr. Bonnor, the third lieutenant, will be glad to keep a special eye on you. Do you understand anything about handling a boat?"

"Yes, sir. I have been accustomed to sailing, rowing, and steering as long as I can remember."

"That is something gained at any rate. Do you know the names of the various ropes and sheets?"

"I do in a vessel of ordinary size, sir. I was so often on board craft that were in my father's hands for repair that I learned a good deal about them, and at any rate can trust myself to go aloft."

"Well, Mr. Wilkinson is in your watch, and as I put you in his charge to start with, I will tell him to act as your instructor in these matters. Please ask him to step here.

"Mr. Wilkinson," he went on, as the midshipman came up, "I shall be obliged if you will do what you can to assist Mr. Blagrove in learning his duties. He has been knocking about among boats and merchant craft since his childhood, and already knows a good deal about them; but naturally there is much to learn in a ship like this. You will, of course, keep your watches as usual at night, but I shall request Mr. Bonnor to release you from all other duties for the present, in order that you may assist Mr. Blagrove in learning the names and uses of all the ropes, and the ordinary routine of his duty. He will, of course, attend the master's class in navigation. There will be no occasion for him to go through the whole routine of a freshly-joined lad in other respects; but he must learn[Pg 175] cutlass and musketry drill from the master-at-arms, and to splice and make ordinary knots from the boatswain's mate. Thank you, that will do for the present."

Lieutenant Bonnor came up to Wilkinson a few minutes later, and told him that he was to consider himself relieved from all general duties at present.

"I hope you won't find this a nuisance, Wilkinson," Edgar said.

"Not at all," the other laughed; "quite the contrary. It gets one off of all sorts of disagreeable routine work, and as you know something about it to begin with, I have no doubt that you will soon pick up your work. A lot of the things that one has to learn when one first joins are not of much use afterwards, and may not have to be done once a year. However, I can lend you books, and if you really want to pick up all the words of command you can study them when you have nothing else to do; and I can tell you there are plenty of times when one is rather glad to have something to amuse one; when one is running with a light wind aft, like this, for instance, we may go on for days without having to touch a sail. Well, we will begin at once. We won't go aloft till you have got your togs; a fellow going aloft in landsmen's clothes always looks rather a duffer. Now, let us see what you know about things."

As the names of the halliards, sheets, and tacks are the same in any square-rigged vessel, Edgar answered all questions readily, and it was only the precise position assigned to each on deck that he had to learn, so that, even on the darkest night, he could at once lay hands on them without hesitation; and in the course of a couple of days he knew these as well as his instructor. On the third morning he put on his midshipman's clothes for the first time.

"You are a great deal stronger fellow than I should have[Pg 176] taken you for," Wilkinson said, as he watched him dressing. "You have a tremendous lot of muscle on the shoulders and arms, and on the back too."

"I took a lot of exercise when I was at school in England," Edgar replied, "and I have been accustomed to riding ever since I was a boy, and for the last five months have almost lived in the saddle. I have done a good deal of rowing too, for I have had the use of a boat as long as I can remember. Of course, I have done a lot of bathing and swimming—you see, the water is so warm that one can stay in it for a long time, and one can bathe all the year round. I cannot even remember being taught to swim, I suppose it came naturally to me. I am sure that my father would never have let me go out in boats as I used to do if he had not known that I was as much at home in the water as out of it."

"Now we will go aloft," Wilkinson said.

Edgar ran up almost as quickly as his companion. He had not only been accustomed to ships in the port of Alexandria, but on the voyage to England and back he had spent much of his time aloft, the captains being friends of his father, and allowing him to do as he liked, as soon as they saw that he was perfectly capable of taking care of himself.

"This is not the first time that you have been aloft, sir," one of the top-men said, as he followed Wilkinson's example, instead of going up through the lubber's hole.

"It is the first time that I have ever gone up the mast of a man-of-war," Edgar replied; "but everything is so big and solid here, that it seems easy after being accustomed to smaller craft. It is a wonderful spread of sail, Wilkinson, after having been on board nothing bigger than a brig. I used to help reef the sails on my way back from Eng[Pg 177]land; but these tremendous sails seem altogether too big to handle."

"So they would be without plenty of hands, but you see we have a great many more men in proportion here than there are on board a merchant craft. Will you go up higher?"

"Certainly." And they went up until nothing but the bare pole, with the pennant floating from its summit, rose above them. "You don't feel giddy at all, Blagrove?"

"Not a bit. If she were rolling heavily perhaps I might be, but she is going on so steadily that I don't feel it at all."

"Then I will begin by giving you a lesson as to what your duties would be if the order were given to send down the upper spars and yards. It is a pleasure teaching a fellow who is so anxious to learn as you are, and who knows enough to understand what you say."

For two hours he sat there explaining to Edgar exactly where his position would be during this operation, and the orders that he would have to give.

"When we get down below," he said, when he had finished, "I will give you all the orders, and you can jot them down, and learn them by heart. The great point, you see, is to fire them off exactly at the right moment. A little too soon or a little too late makes all the difference. It is generally a race between the top-men of the different masts, and there is nothing that the men think more of than smartness in getting down all the upper gear. When you have got all the words of command by heart perfectly, you shall come with me the first time the order is given to send down the spars and yards, so as to see exactly where the orders come in. It is a thing that we very often practise. In fact, as a rule, it is done every evening when we are cruising, or in harbour, or at Spithead,[Pg 178] or that sort of thing. When it is a race between the different ships of a squadron, it is pretty bad for the top-men who are the last to get their spars down. But, you see, as we are on a passage I don't suppose we shall send down spars till we get to Constantinople."

"What are we going there for?"

"As far as I can understand, the captain is going on a sort of diplomatic mission. His brother is our ambassador there, and he is appointed to act with him in some sort of diplomatic way, I suppose, to arrange what troops the Sultan is going to send against the French, and what we are to do to help him, and what subvention is to be paid him, and all that sort of thing. I expect you will be pretty busy while we are there. Do you understand Turkish?"

"Yes, it is very like Arabic. All the officials and upper classes in Egypt are Turks, and one hears more Turkish than Arabic, except among the Bedouin tribes."

While they were talking they were leisurely descending the shrouds side by side. As soon as they gained the deck, the captain's steward came up to Edgar, and said that Sir Sidney Smith would be glad to see him and Mr. Wilkinson to dinner that evening. The captain had abstained from inviting him until he should have got his uniform, thinking that he would find it uncomfortable sitting down in civilian dress. The fact that he was going to dine late in no way interfered with Edgar's enjoyment of his mid-day meal. During the two days he had been on board, he had got on friendly terms with all his messmates excepting Condor, who studiously abstained from noticing him in any way. The younger midshipmen he bullied unmercifully, and had a general dictatorial way with the others that made Edgar frequently long for the opportunity of giving him a lesson.[Pg 179]

He had no doubt that Condor had determined to postpone the occasion until they had left the Pireus, at which point they were to call, as his service might be required there to interpret. Once away from the island, he would not be likely to be called upon to translate until they arrived at Constantinople.

It was a pleasant dinner in Sir Sidney Smith's cabin. There were present the first and third lieutenants, the captain of the marines, the doctor, Wilkinson, and Edgar. Sir Sidney Smith was a delightful host; he possessed a remarkable charm of manner, was most thoughtful and kind to all his subordinates, and, though strict in all matters of discipline, treated his officers as gentlemen and on terms of equality in his own cabin. He had already accomplished many dashing exploits in the Baltic and elsewhere, and was beloved both by the sailors and officers. It was a time when life in the navy was very rough, when the lash was unsparingly used for the smallest offences, and when too many ships were made floating hells by the tyranny of their commanders.

"I should have asked you to dinner on the day that you came on board, Mr. Blagrove," Sir Sidney said kindly, as the two midshipmen entered, "but I thought that you might prefer my not doing so until you got your uniform. It has been some privation for myself, for I am anxious to hear from you some details as to what has been doing in Egypt, of which, of course, we know next to nothing at

Comments (0)