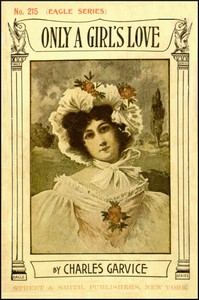

Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Garvice

Book online «Only a Girl's Love, Charles Garvice [a book to read .txt] 📗». Author Charles Garvice

Wandering thus she suddenly bethought her of a picture that stood with its face to the wall, and swooping down on it, as one does on a suddenly remembered treasure, she took up Leycester Wyndward's portrait, and gazing long and eagerly at it, suddenly bent and kissed it. She knew now what the smile in those dark eyes meant; she knew now how the lovelight could flash from them.

"Uncle was right," she murmured with a smile that was half sad. "There is no woman who could resist those eyes if they said 'I love you.'"

She put the portrait down upon the cabinet, so that she could see it when she chose to look at it, and abstractedly began to set[101] the room in order, putting a picture straight here and setting the books upon their shelves, stopping occasionally to glance at the handsome eyes watching her from the top of the cabinet. As often happens when the mind is set on one thing and the hands upon another, she met with an accident. In one corner of the room stood a three-cornered what-not of Japanese work, inclosed by doors inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl; in attempting to set a bronze straight upon the top of this piece of furniture while she looked at the portrait of her heart's lord and master, she let the bronze slip, and in the endeavor to save it from falling, overturned the what-not.

It fell with the usual brittle sounding crash which accompanies the overthrow of such bric-a-brac, and the doors being forced open, out poured a miscellaneous collection of valuable but useless articles.

With a little exclamation of self-reproach and dismay, Stella went down on her knees to collect the scattered curios. They were of all sorts; bits of old china from Japan, medals, and coins of ancient date, and some miniatures in carved frames.

Stella eyed each article as she picked it up with anxious criticism, but fortunately nothing appeared the worse for the downfall, and she was putting the last thing, a miniature, in its accustomed place, when the case flew open in her hand and a delicately painted portrait on ivory looked up at her. Scarcely glancing at it, she was about to replace it in the case, when an inscription on the back caught her eye, and she carried case and miniature to the light.

The portrait was that of a boy, a fair-haired boy, with a smiling mouth and laughing blue eyes. It was a pretty face, and Stella turned it over to read the inscription.

It consisted of only one word, "Frank."

Stella looked at the face again listlessly, but suddenly something in it—a resemblance to someone whom she knew, and that intimately—flashed upon her. She looked again more curiously. Yes, there could be no doubt of it; the face bore a certain likeness to that of her uncle. Not only to her uncle, but to herself, for raising her eyes from the portrait to the mirror she saw a vague something—in expression only perhaps—looking at her from the glass as it did from the portrait.

"Frank, Frank," she murmured; "I know no one of that name. Who can it be?"

She went back to the cabinet, and took out the other miniatures, but they were closed, and the spring which she had touched accidentally of the one of the boy she could not find in the others.

There was an air of mystery about the matter, which not a little heightened by the lateness of the hour and the solemn silence that reigned in the house, oppressed and haunted her.

With a little gesture of repudiation she put the boy's face into its covering, and replaced it in the cabinet. As she did so she glanced up at that other face smiling down at her, and started, and a sudden thought, half-weird, half-prophetical, flashed across her mind.

[102]

It was the portrait of Lord Leycester which had greeted her on the night of her arrival, and foreshadowed all that had happened to her. Was there anything of significance in this chance discovery of the child's face?

With a smile of self-reproach she put the fantastic idea from her, and setting the beloved face in its place amongst the other canvases, took the candle from the table, and stole quietly up-stairs.

But when she slept the boy's face haunted her, and mingled in her dreams with that of Lord Leycester's.

CHAPTER XV.Lord Leycester stood for a minute or two looking after the carriage that bore Stella and her uncle away; then he returned to the house. They were a hot-headed race, these Wyndwards, and Leycester was, to put it mildly, as little capable of prudence or calculation as any of his line; but though his heart was beating fast, and the vision of the beautiful girl in all her young unstained loveliness danced before his eyes as he crossed the hall, even he paused a moment to consider the situation. With a grim smile he felt forced to confess that it was rather a singular one.

The heir of Wyndward, the hope of the house, the heir to an ancient name and a princely estate, had plighted his troth to the niece of a painter—a girl, be she beautiful as she might, without either rank or wealth, to recommend her to his parents!

He might have chosen from the highest and the wealthiest; the highest and the wealthiest had been, so to speak, at his feet. He knew that no dearer wish existed in his mother's heart of hearts than that he should marry and settle. Well, he was going to marry and settle. But what a marriage and settlement it would be! Instead of adding luster to the already illustrious name, instead of adding power to the already influential race of Wyndward, it would, in the earl and countess's eyes, in the opinion of the world, be nothing but a mesalliance.

He paused in the corridor, the two footmen eying him with covert and respectful attention, and a smile curved his lips as he pictured to himself the manner in which the proud countess would receive his avowal of love for Stella Etheridge, the painter's niece.

Even as it was, he was quite conscious that he had gone very far indeed this evening toward provoking the displeasure of the countess. He had almost neglected the brilliant gathering for the sake of this unknown girl; he had left his mother's oldest friends, even Lady Lenore herself, to follow Stella. How would they receive him?

With a smile half-defiant, half anticipatory of amusement, he motioned to the servants to withdraw the curtain, and entered the room.

Some of the ladies had already retired; Lady Longford had gone for one, but Lady Lenore still sat on her couch attended by a circle of devoted adherents. As he entered, the countess,[103] without seeming to glance at him, saw him, and noticed the peculiar expression on his face.

It was the expression which it always wore when he was on the brink of some rashly mad exploit.

Leycester had plenty of courage—too much, some said. He walked straight up to the countess, and stood over her.

"Well, mother," he said, almost as if he were challenging her, "what do you think of her?"

The countess lifted her serene eyes and looked at him. She would not pretend to be ignorant of whom he meant.

"Of Miss Etheridge?" she said. "I have not thought about her. If I had, I should say that she was a very pleasant-looking girl."

"Pleasant-looking!" he echoed, and his eyebrows went up. "That is a mild way of describing her. She is more than pleasant."

"That is enough for a young girl in her position," said the countess.

"Or in any," said a musical voice behind him, and Lord Leycester, turning round, saw Lady Lenore.

"That was well said," he said, nodding.

"She is more than pleasant," said Lady Lenore, smiling at him as if he had won her warmest approbation by neglecting her all the evening. "She is very pretty, beautiful, indeed, and so—may I say the word, dear Lady Wyndward?—so fresh!"

The countess smiled with her even brows unclouded.

"A school-girl should be fresh, as you put it Lenore, or she is nothing."

Lord Leycester looked from one to the other, and his gaze rested on Lady Lenore's superb beauty with a complacent eye.

To say that a man in love is blind to all women other than the one of his heart is absurd. It is not true. He had never admired Lady Lenore more than he did this moment when she spoke in Stella's defense; but he admired her while he loved Stella.

"You are right, Lenore," he said. "She is beautiful."

"I admire her exceedingly," said Lady Lenore, smiling at him as if she knew his secret and approved of it.

The countess glanced from one to the other.

"It is getting late," she said. "You must go now, Lenore."

Lady Lenore bowed her head. She, like all else who came within the circle of the mistress of Wyndward, obeyed her.

"Very well, I am a little tired. Good-night!"

Lord Leycester took her hand, but held it a moment. He felt grateful to her for the word spoken on Stella's behalf.

"Let me see you to the corridor," said Lord Leycester.

And with a bow which comprehended the other occupants of the room, he accompanied her.

They walked in silence to the foot of the stairs, then Lady Lenore held out her hand.

"Good-night," she said, "and happy dreams."

He looked at her curiously. Was there any significance in her[104] words?—did she know all that had passed between Stella and himself?

But nothing more significant met his scrutiny than the soft languor of her eyes, and pressing her hand as he bent over it, he murmured:

"I wish you the same."

She nodded smilingly to him, and went away, and he turned back to the hall.

As he did so the billiard-room door opened, and Lord Charles put out his head.

"One game, Ley?" he said.

Lord Leycester shook his head.

"Not to-night, Charlie."

Lord Charles looked at him, then laughed, and withdrew his head.

Leycester sauntered down the hall and back again; he felt very restless and disinclined for bed; Stella's voice was ringing in his ears, Stella's lips still clung with that last soft caress to his. He could not face the laughter and hard voices of the billiard-room; it would be profanation! With a sudden turn he went lightly up the stairs and entered his own room.

Throwing himself into a chair, he folded his arms behind his head and closed his eyes, to call up a vision of the girl who had rested on his breast—whose sweet, pure lips had murmured "I love you!"

"My darling!" he whispered—"my darling love! I have never known it till now. And I shall see you to-morrow, and hear you whisper that again, 'I love you!' And it's ME she loves, not the viscount and heir to Wyndward, but me, Leycester! Leycester—it was a hard, ugly name until she spoke it—now it sounds like music. Stella, my star, my angel!"

Suddenly his reverie was disturbed by a knock at the door. With a start, he came back to reality, and got up, but before he could reach the door it opened, and the countess came in.

"Not in bed?" she said, with a smile.

"I have only just come up," he replied.

The countess smiled again.

"You have been up nearly half an hour."

He was almost guilty of a blush.

"So long!" he said, "I must have been thinking."

And he laughed, as he drew a chair forward. He waited until she was seated before he resumed his own; never, by word or deed, did he permit himself to grow lax in courtesy to her; and then he looked up at her with a smile.

"Have you come for a chat, my lady?" he said, calling her by her title in the mock-serious way in which he was accustomed to address her when they were alone.

"Yes, I have come for a chat, Leycester," she said, quietly.

"Does that mean a scold?" he asked, raising his eyebrows, but still smiling. "Your tone is suspicious, mother. Well, I am at your mercy."

"I have nothing to scold you for," said the countess, leaning[105] back in the comfortable chair—all the chairs were comfortable in these rooms of his. "Do you feel that you deserve one?"

Lord Leycester was silent. If he had answered he might have been compelled to admit that perhaps there was some excuse for complaint in regard to his conduct that evening; silence was safest.

"No, I have not come to scold you,

Comments (0)