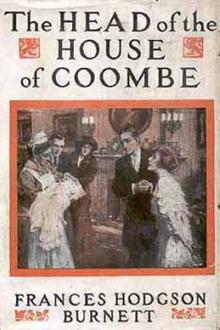

The Head of the House of Coombe, Frances Hodgson Burnett [adult books to read txt] 📗

- Author: Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Performer: -

Book online «The Head of the House of Coombe, Frances Hodgson Burnett [adult books to read txt] 📗». Author Frances Hodgson Burnett

Accepting the situation in its entirety, Dowson had seen that it was well to first reach Lord Coombe with any need of the child’s. Afterwards, the form of presenting it to Mrs. Gareth-Lawless must be gone through, but if she were first spoken to any suggestion might be forgotten or intentionally ignored.

Dowson became clever in her calculations as to when his lordship might be encountered and where—as if by chance, and therefore, quite respectfully. Sometimes she remotely wondered if he himself did not make such encounters easy for her. But his manner never altered in its somewhat stiff, expressionless chill of indifference. He never was kindly in his manner to the child if he met her. Dowson felt him at once casual and “lofty.” Robin might have been a bit of unconsidered rubbish, the sight of which slightly bored him. Yet the singular fact remained that it was to him one must carefully appeal.

One afternoon Feather swept him, with one or two others, into the sitting-room with the round window in which flowers grew. Robin was sitting at a low table making pothooks with a lead pencil on a piece of paper Dowson had given her. Dowson had, in fact, set her at the task, having heard from Jennings that his lordship and the other afternoon tea drinkers were to be brought into the “Palace” as Feather ironically chose to call it. Jennings rather liked Dowson, and often told her little things she wanted to know. It was because Lord Coombe would probably come in with the rest that Dowson had set the low, white table in the round windows and suggested the pothooks.

In course of time there was a fluttering and a chatter in the corridor. Feather was bringing some new guests, who had not seen the place before.

“This is where my daughter lives. She is much grander than I am,” she said.

“Stand up, Miss Robin, and make your curtsey,” whispered Dowson. Robin did as she was told, and Mrs. Gareth-Lawless’ pretty brows ran up.

“Look at her legs,” she said. “She’s growing like Jack and the Bean Stalk—though, I suppose, it was only the Bean Stalk that grew. She’ll stick through the top of the house soon. Look at her legs, I ask you.”

She always spoke as if the child were an inanimate object and she had, by this time and by this means, managed to sweep from Robin’s mind all the old, babyish worship of her loveliness and had planted in its place another feeling. At this moment the other feeling surged and burned.

“They are beautiful legs,” remarked a laughing young man jocularly, “but perhaps she does not particularly want us to look at them. Wait until she begins skirt dancing.” And everybody laughed at once and the child stood rigid—the object of their light ridicule—not herself knowing that her whole little being was cursing them aloud.

Coombe stepped to the little table and bestowed a casual glance on the pencil marks.

“What is she doing?” he asked as casually of Dowson.

“She is learning to make pothooks, my lord,” Dowson answered. “She’s a child that wants to be learning things. I’ve taught her her letters and to spell little words. She’s quick—and old enough, your lordship.”

“Learning to read and write!” exclaimed Feather.

“Presumption, I call it. I don’t know how to read and write—least I don’t know how to spell. Do you know how to spell, Collie?” to the young man, whose name was Colin. “Do you, Genevieve? Do you, Artie?”

“You can’t betray me into vulgar boasting,” said Collie. “Who does in these days? Nobody but clerks at Peter Robinson’s.”

“Lord Coombe does—but that’s his tiresome superior way,” said Feather.

“He’s nearly forty years older than most of you. That is the reason,” Coombe commented. “Don’t deplore your youth and innocence.”

They swept through the rooms and examined everything in them. The truth was that the—by this time well known—fact that the unexplainable Coombe had built them made them a curiosity, and a sort of secret source of jokes. The party even mounted to the upper story to go through the bedrooms, and, it was while they were doing this, that Coombe chose to linger behind with Dowson.

He remained entirely expressionless for a few moments. Dowson did not in the least gather whether he meant to speak to her or not. But he did.

“You meant,” he scarcely glanced at her, “that she was old enough for a governess.”

“Yes, my lord,” rather breathless in her hurry to speak before she heard the high heels tapping on the staircase again. “And one that’s a good woman as well as clever, if I may take the liberty. A good one if—”

“If a good one would take the place?”

Dowson did not attempt refutation or apology. She knew better.

He said no more, but sauntered out of the room.

As he did so, Robin stood up and made the little “charity bob” of a curtsey which had been part of her nursery education. She was too old now to have refused him her hand, but he never made any advances to her. He acknowledged her curtsey with the briefest nod.

Not three minutes later the high heels came tapping down the staircase and the small gust of visitors swept away also.

The interview which took place between Feather and Lord Coombe a few days later had its own special character.

“A governess will come here tomorrow at eleven o’clock,” he said. “She is a Mademoiselle Valle. She is accustomed to the educating of young children. She will present herself for your approval. Benby has done all the rest.”

Feather flushed to her fine-spun ash-gold hair.

“What on earth can it matter!” she cried.

“It does not matter to you,” he answered; “it chances—for the time being—to matter to ME.”

“Chances!” she flamed forth—it was really a queer little flame of feeling. “That’s it. You don’t really care! It’s a caprice—just because you see she is going to be pretty.”

“I’ll own,” he admitted, “that has a great deal to do with it.”

“It has everything to do with it,” she threw out. “If she had a snub nose and thick legs you wouldn’t care for her at all.”

“I don’t say that I do care for her,” without emotion. “The situation interests me. Here is an extraordinary little being thrown into the world. She belongs to nobody. She will have to fight for her own hand. And she will have to FIGHT, by God! With that dewy lure in her eyes and her curved pomegranate mouth! She will not know, but she will draw disaster!”

“Then she had better not be taught anything at all,” said Feather. “It would be an amusing thing to let her grow up without learning to read or write at all. I know numbers of men who would like the novelty of it. Girls who know so much are a bore.”

“There are a few minor chances she ought to have,” said Coombe. “A governess is one. Mademoiselle Valle will be here at eleven.”

“I can’t see that she promises to be such a beauty,” fretted Feather. “She’s the kind of good looking child who might grow up into a fat girl with staring black eyes like a barmaid.”

“Occasionally pretty women do abhor their growing up daughters,” commented Coombe letting his eyes rest on her interestedly.

“I don’t abhor her,” with pathos touched with venom. “But a big, lumping girl hanging about ogling and wanting to be ogled when she is passing through that silly age! And sometimes you speak to me as a man speaks to his wife when he is tired of her.”

“I beg your pardon,” Coombe said. “You make me feel like a person who lives over a shop at Knightsbridge, or in bijou mansion off Regent’s Park.”

But he was deeply aware that, as an outcome of the anomalous position he occupied, he not infrequently felt exactly this.

That a governess chosen by Coombe—though he would seem not to appear in the matter—would preside over the new rooms, Feather knew without a shadow of doubt.

A certain almost silent and always highbred dominance over her existence she accepted as the inevitable, even while she fretted helplessly. Without him, she would be tossed, a broken butterfly, into the gutter. She knew her London. No one would pick her up unless to break her into smaller atoms and toss her away again. The freedom he allowed her after all was wonderful. It was because he disdained interference.

But there was a line not to be crossed—there must not even be an attempt at crossing it. Why he cared about that she did not know.

“You must be like Caesar’s wife,” he said rather grimly, after an interview in which he had given her a certain unsparing warning.

“And I am nobody’s wife. What did Caesar’s wife do?” she asked.

“Nothing.” And he told her the story and, when she had heard him tell it, she understood certain things clearly.

Mademoiselle Valle was an intelligent, mature Frenchwoman. She presented herself to Mrs. Gareth-Lawless for inspection and, in ten minutes, realized that the power to inspect and sum up existed only on her own side. This pretty woman neither knew what inquiries to make nor cared for such replies as were given. Being swift to reason and practical in deduction, Mademoiselle Valle did not make the blunder of deciding that this light presence argued that she would be under no supervision more serious. The excellent Benby, one was made aware, acted and the excellent Benby, one was made aware, acted under clearly defined orders. Milord Coombe—among other things the best dressed and perhaps the least comprehended man in London—was concerned in this, though on what grounds practical persons could not explain to themselves. His connection with the narrow house on the right side of the right street was entirely comprehensible. The lenient felt nothing blatant or objectionable about it. Mademoiselle Valle herself was not disturbed by mere rumour. The education, manner and morals of the little girl she could account for. These alone were to be her affair, and she was competent to undertake their superintendence.

Therefore, she sat and listened with respectful intelligence to the birdlike chatter of Mrs. Gareth-Lawless. (What a pretty woman! The silhouette of a jeune fille!)

Mrs. Gareth-Lawless felt that, on her part, she had done all that was required of her.

“I’m afraid she’s rather a dull child, Mademoiselle,” she said in farewell. “You know children’s ways and you’ll understand what I mean. She has a trick of staring and saying nothing. I confess I wish she wasn’t dull.”

“It is impossible, madame, that she should be dull,” said Mademoiselle, with an agreeably implicating smile. “Oh, but quite impossible! We shall see.”

Not many days had passed before she had seen much. At the outset, she recognized the effect of the little girl with the slender legs and feet and the dozen or so of points which go to make a beauty. The intense eyes first and the deeps of them. They gave one furiously to think before making up one’s mind. Then she noted the perfection of the rooms added to the smartly inconvenient little house. Where had the child lived before the addition had been built? Thought and actual architectural genius only could have done this. Light and even as much sunshine as London will vouchsafe, had been arranged for. Comfort, convenience, luxury, had been provided. Perfect colour and excellent texture had evoked actual charm. Its utter unlikeness to the quarters London usually

Comments (0)