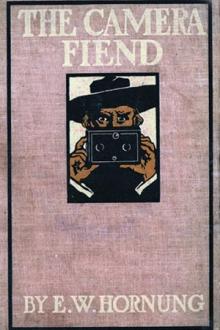

The Camera Fiend, E. W. Hornung [important of reading books txt] 📗

- Author: E. W. Hornung

- Performer: -

Book online «The Camera Fiend, E. W. Hornung [important of reading books txt] 📗». Author E. W. Hornung

“But—but I don't want to leave you!” he blurted out at last.

“But I want you to,” she returned promptly and firmly, though not without a faint smile.

It was leaving her with a villain that he minded; but he could not get that out, except thus bluntly, nor could he denounce the doctor now as he had done when his blood was up. Besides, the man was a different man to his niece; all that redeemed him went out to her. Pocket did not think he was peculiar there; in fact, he thought romantically enough about the girl, with her dark hair all over her pink dressing-gown, and ivory insteps peeping out of those soft slippers especially when the vision was lost for ever, and he upstairs making himself as presentable as he could in a few minutes. But it seemed she was busy in the same way, and she took longer over it. He found the breakfast things on the table, the kettle on the gas-stove, but no Phillida to make the tea. He could not help wishing she would be quick; if he was going, the sooner he went the better, but he was terribly divided in his desires. He hated the thought of [pg 228] deserting a comrade, who was also a girl, and such a girl! He could only face it with the fixed intention of coming back to the rescue of his heroine, he the hero of their joint romance. But for his own immediate freedom he was already unheroically eager. And yet he could deliberately fit the broken negatives together, on the white tablecloth, partly to pass the time, partly out of a boyish bravado which involved little real risk; for the doctor had not yet been gone an hour; and a loaded revolver is a loaded revolver, be it brandished by man or boy.

The piecing of the plates was like a children's puzzle, only easier, because the pieces were not many. One of the reconstructed negatives was of painful interest; it reminded Pocket of the fatal one smashed to atoms by Baumgartner in the pink porcelain trough. There were trees again, only leafless, and larger, and there was a larger figure sprawling on a bench. Pocket felt he must have a print of this; he remembered having seen printing-frames and tubes of sensitised paper in the other room; and hardly had he filled his frame and placed it in position, than Phillida ran down stairs, and he told her what he had done.

“I wish you hadn't,” she said nervously, as she made mechanical preparations with pot and kettle. “It would only make matters worse if my uncle came in now.”

[pg 229]“But he wasn't back on Friday before ten or eleven.”

“You never know!”

Pocket spoke out with a truculence which his brothers had inherited, but not he, valiantly as he might try to follow a family example.

“I don't care! I can't help it if he does come. I'll tell him exactly what I've done, and why, and exactly what I'm going to do next. I give him leave to stop me if he can.”

“I'm afraid he won't wait for that. But I wish you had waited for his leave before printing his negative.”

Pocket jumped up from table, and ran to the printing-frame in the sunny room at the back. He had been reminded of it only just in time. It was a rather dark print that he first examined, one half at a time, and then extracted from the frame. It was meshed with white veils, showing the joins of the broken plate. But it had been an excellent negative originally. And it was still good enough to hold Pocket rooted to the carpet in the sunny room, until Phillida came in after him, and stood looking over his shoulder.

“I know that place!” said she at once. “It's Holland Walk, in Kensington.”

He turned to her quickly.

[pg 230]“The place where there was a suicide or something not long ago?”

“The very place!” exclaimed the girl, looking up from the darkening print.

“I remember my uncle would take me to see it next day. He's always so interested in mysteries. I'm sure that's the very spot he showed me as the one where it must have happened.”

“Did he take the photograph then?”

“No; he hadn't his camera with him.”

“Then this is the suicide, or whatever it was!” cried Pocket, in uncontrollable excitement. “It's not only the place; it's the thing itself. Look at that man on the bench!”

The girl took a long look nearer the window.

“How horrible!” she shuddered. “His head looks as though it were falling off! He might be dying.”

“Dying or dead,” said Pocket, “at the very second the plate was exposed!”

She looked at him in blank horror. His own horror was no less apparent, but it was more understanding. He had Baumgartner's own confession of his attempts to secure admission to hospital death-beds, even to executions; he expounded Baumgartner on the whole subject, briefly, clumsily, inaccurately enough, and yet with a certain graphic power which brought those incredible theories [pg 231] home to his companion as forcibly as Baumgartner himself had brought them home to Pocket. It was the first she had ever heard of them. But then he had never discussed his photography with her, never showed her plate or print. That it was not merely a hobby, that he was an inventor, a pioneer, she had always felt, without dreaming in what direction or to what extent. Even now she seemed unable to grasp the full significance of the print from the broken negative; and when she would have examined it afresh, there was nothing to see; the June sunshine had done its work, and blotted out the repulsive picture even as she held it in her hands.

“Then what do you think?” she asked at last; her voice was thin and strained with formless terrors.

“I think that Dr. Baumgartner has the strangest power of any human being I ever heard of; he can make you do anything he likes, whether you like it yourself or not. The newspapers have been raking up this case in connection with—mine—and I see that one theory was that the man in this broken negative committed suicide. Well, if he did, I firmly believe that Dr. Baumgartner was there and willed him to do it!”

“He must have been there if he took the photograph.”

“Is there another man alive who tries these [pg 232] things? I've told you all he told me about it, but I haven't told you all he said about the value of human life.”

“Nor need you! He makes no secret of his opinion about that!”

“Then put the two things together, and where do they lead you? To these murders committed with the mad idea of taking the spirit in its flight from the flesh; that's his own way of putting it, not mine.”

“But I thought your case was an accident pure and simple?”

“On my part, certainly; but how do I know he couldn't get more power over me in my sleep than at any other time? He saw me walking in my sleep with this wretched revolver. He said himself I'd given him the chance of a lifetime. You may be sure he meant before that poor man's death, not after it.”

“It isn't possible,” declared Phillida, as though she had laid hold of one solid certainty in a sea of floating hypotheses. “And I know he hasn't a pistol of his own,” she added, lest he should simplify his charge.

But there they were agreed.

“He hadn't one on him that morning; that I can swear,” said Pocket, impartially disposing of the idea. “Mine was the only one in that cape of [pg 233] his, because I once jolly nearly had it out again when he came back into the room. There was nothing of the sort in his other coat, or anywhere else about him, or I couldn't have helped seeing it.” Phillida accepted this statement only too thankfully. She beamed on the boy, as if in recognition of a piece of downright magnanimity towards an enemy whom she could now understand his regarding in that light. If only he would go before the enemy returned! If her uncle had such a power over him as he himself seemed to feel, then that was all the more reason for him to go quickly. But Pocket was not the man to get up and run like that. Perhaps he enjoyed displaying his bravery on the point, and keeping his companion on tenter-hooks on his account; at any rate he insisted on finishing his breakfast, and gave further free expression to the wildest surmises as he did so. And yet he was even then on the brink of a discovery which was some excuse for the wildest of them all, while it demanded a fresh solution of the whole affair.

He had been fingering the recovered weapon in his pocket, almost fondling it, though with mingled feelings, as the Prodigal Son of his small possessions; suddenly it leapt out like a live thing in his hand, and clattered on the table between the girl and boy. It was a wonder neither of them was shot dead in his excitement. His whole face [pg 234] was altered; but so was his whole life. She could not understand his incoherent outburst; she only knew that he was twisting the chambers round and round under her nose, and that there appeared to be live cartridges in all six.

“Don't you see?” the words came pouring. “Not one of them's been fired—it's as I loaded it myself the other night! It can't have been this revolver at all!”

“But you must have known whether you fired or not?”

“I tell you I was walking in my sleep till the row woke me. I'd only heard it once before, in a room. It sounded loud enough for the open air, though I do remember wondering I hadn't felt any kick. But I was so dazed, and there was this beastly thing in my hand; and he took it from me in such a rage that of course I believed I'd let it off. But now I can see I can't have done. It wasn't my revolver and it wasn't me!”

“Yet you say yourself my uncle didn't carry one?”

“I'll swear he didn't; but there's another man in all this! There was the man they arrested on Saturday—the man I was so keen to set free!”

The boy's laugh grated; he was beside himself with righteous joy. What was it to him

Comments (0)