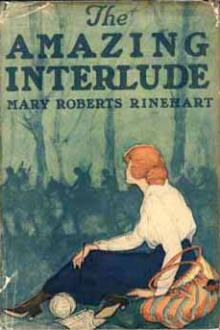

The Amazing Interlude, Mary Roberts Rinehart [diy ebook reader TXT] 📗

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Book online «The Amazing Interlude, Mary Roberts Rinehart [diy ebook reader TXT] 📗». Author Mary Roberts Rinehart

"To meet me?"

"I expect the Ladies' Aid Society wanted to get into the papers again," he said rather grimly. "They are merry little advertisers, all right."

"I don't think that, Harvey."

"Well, I do," he said, and brought her to a stop facing a smart little car, very new, very gay.

"How do you like it?" he asked.

"Like it? Why, it's not yours, is it?"

"Surest thing you know. Or, rather, it's ours. Had a few war babies, and they grew up."

Sara Lee looked at it, and for just an instant, a rather sickening instant, she saw Henri's shattered low car, battle-scarred and broken.

"It's—lovely," said Sara Lee. And Harvey found no fault with her tone.

Sara Lee had intended to go to Anna's, for a time at least. But she found that Belle was expecting her and would not take no.

"She's moved the baby in with the others," Harvey explained as he took the wheel. "Wait until you see your room. I knew we'd be buying furniture soon, so I fixed it up."

He said nothing for a time. He was new to driving a car, and the traffic engrossed him. But when they had reached a quieter neighborhood he put a hand over hers.

"Good God, how I've been hungry for you!" he said. "I guess I was pretty nearly crazy sometimes." He glanced at her apprehensively, but if she knew his connection with her recall she showed no resentment. As a matter of fact there was in his voice something that reminded her of Henri, the same deeper note, almost husky.

She was, indeed, asking herself very earnestly what was there in her of all people that should make two men care for her as both Henri and Harvey cared. In the humility of all modest women she was bewildered. It made her rather silent and a little sad. She was so far from being what they thought her.

Harvey, stealing a moment from the car to glance at her, saw something baffling in her face.

"Do you still care, Sara Lee?" he asked almost diffidently. "As much as ever?"

"I have come back to you," she said after an imperceptible pause.

"Well, I guess that's the answer."

He drew a deep satisfied breath. "I used to think of you over there, and all those foreigners in uniform strutting about, and it almost got me, some times."

And again, as long before, he read into her passivity his own passion, and was deeply content.

Belle was waiting on the small front porch. There was an anxious frown on her face, and she looked first, not at Sara Lee, but at Harvey. What she saw there evidently satisfied her, for the frown disappeared. She kissed Sara Lee impulsively.

All that afternoon, much to Harvey's resentment, Sara Lee received callers. The Ladies' Aid came en masse and went out to the dining-room and there had tea and cake. Harvey disappeared when they came.

"You are back," he said, "and safe, and all that. But it's not their fault. And I'll be hanged if I'll stand round and listen to them."

He got his hat and then, finding her alone in a back hall for a moment, reverted uneasily to the subject.

"There are two sides to every story," he said. "They're going to knife me this afternoon, all right. Damned hypocrites! You just keep your head, and I'll tell you my side of it later."

"Harvey," she said slowly, "I want to know now just what you did. I'm not angry. I've never been angry. But I ought to know."

It was a very one-sided story that Harvey told her, standing in the little back hall, with Belle's children hanging over the staircase and begging for cake. Yet in the main it was true. He had reached his limit of endurance. She was in danger, as the photograph plainly showed. And a fellow had a right to fight for his own happiness.

"I wanted you back, that's all," he ended. And added an anticlimax by passing a plate of sliced jelly roll through the stair rail to the clamoring children.

Sara Lee stood there for a moment after he had gone. He was right, or at least he had been within his rights. She had never even heard of the new doctrine of liberty for women. There was nothing in her training to teach her revolt. She was engaged to Harvey; already, potentially, she belonged to him. He had interfered with her life, but he had had the right to interfere.

And also there was in the back of her mind a feeling that was almost guilt. She had let Henri tell her he loved her. She had even kissed him. And there had been many times in the little house when Harvey, for days at a time, had not even entered her thoughts. There was, therefore, a very real tenderness in the face she lifted for his good-by kiss.

To Belle in the front hall Harvey gave a firm order.

"Don't let any reporters in," he said warningly. "This is strictly our affair. It's a private matter. It's nobody's business what she did over there. She's home. That's all that matters."

Belle assented, but she was uneasy. She knew that Harvey was unreasonably, madly jealous of Sara Lee's work at the little house of mercy, and she knew him well enough to know that sooner or later he would show that jealousy. She felt, too, that the girl should have been allowed her small triumph without interference. There had been interference enough already. But it was easier to yield to Harvey than to argue with him.

It was rather a worried Belle who served tea that afternoon in her dining room, with Mrs. Gregory pouring; the more uneasy, because already she divined a change in Sara Lee. She was as lovely as ever, even lovelier. But she had a poise, a steadiness, that were new; and silences in which, to Belle's shrewd eyes, she seemed to be weighing things.

Reporters clamored to see Sara Lee that day, and, failing to see her, telephoned Harvey at his office to ask if it was true that she had been decorated by the King. He was short to the point of affront.

"I haven't heard anything about it," he snapped. "And I wouldn't say if I had. But it's not likely. What d'you fellows think she was doing anyhow? Leading a charge? She was running a soup kitchen. That's all."

He hung up the receiver with a jerk, but shortly after that he fell to pacing his small office. She had not said anything about being decorated, but the reporters had said it had been in a London newspaper. If she had not told him that, there were probably many things she had not told him. But of course there had been very little time. He would see if she mentioned it that night.

Sara Lee had had a hard day. The children loved her. In the intervals of calls they crawled over her, and the littlest one called her Saralie. She held the child in her arms close.

"Saralie!" said the child, over and over; "Saralie! That's your name. I love your name."

And there came, echoing in her ears, Henri and his tender Saralie.

There was an oppression on her too. Her very bedroom thrust on her her approaching marriage. This was her own furniture, for her new home. It was beautiful, simple and good. But she was not ready for marriage. She had been too close to the great struggle to be prepared to think in terms of peace so soon. Perhaps, had she dared to look deeper than that, she would have found something else, a something she had not counted on.

She and Belle had a little time after the visitors had gone, before Harvey came home. They sat in Belle's bedroom, and her sentences were punctuated by little backs briskly presented to have small garments fastened, or bows put on stiffly bobbed yellow hair.

"Did you understand my letter?" she asked. "I was sorry I had sent it, but it was too late then."

"I put your letter and—theirs, together. I supposed that Harvey—"

"He was about out of his mind," Belle said in her worried voice. "Stand still, Mary Ellen! He went to Mrs. Gregory, and I suppose he said a good bit. You know the way he does. Anyhow, she was very angry. She called a special meeting, and—I tried to prevent their recalling you. He doesn't know that, of course."

"You tried?"

"Well, I felt as though it was your work," Belle said rather uncomfortably. "Bring me the comb, Alice. I guess we get pretty narrow here and—I've been following things more closely since you went over. I know more than I did. And, of course, after one marries there isn't much chance. There are children and—" Her face twisted. "I wish I could do something."

She got up and brought from the dresser a newspaper clipping.

"It's the London newspaper," she explained. "I've been taking it, but Harvey doesn't know. He doesn't care much for the English. This is about your being decorated."

Sara Lee held it listlessly in her hands.

"Shall I tell him, Belle?" she asked.

Belle hesitated.

"I don't believe I would," she said forlornly. "He won't like it. That's why I've never showed him that clipping. He hates it all so."

Sara Lee dressed that evening in the white frock. She dressed slowly, thinking hard. All round her was the shiny newness of her furniture, a trifle crowded in Belle's small room. Sara Lee had a terrible feeling of being fastened in by it. Wherever she turned it gleamed. She felt surrounded, smothered.

She had meant to make a clean breast of things—of the little house, and of Henri, and of the King, pinning the medal on her shabby black jacket and shaking hands with her. Henri she must tell about—not his name of course, nor his madness, nor even his love. But she felt that she owed it to Harvey to have as few secrets from him as possible. She would tell about what the boy had done for her, and how he, and he alone, had made it all possible.

Surely Harvey would understand. It was a page that was closed. It had held nothing to hurt him. She had come back.

She stood by her window, thinking. And a breath of wind set the leaves outside to rustling. Instantly she was back again in the little house, and the sound was not leaves, but the shuffling of many stealthy feet on the cobbles of the street at night, that shuffling that was so like the rustling of leaves in a wood or the murmur of water running over a stony creek bed.

XXV

It was clear to Sara Lee from the beginning of the evening that Harvey did not intend to hear her story. He did not say so; indeed, for a time he did not talk at all. He sat with his arms round her, content just to have her there.

"I have a lot of arrears to make up," he said. "I've got to get used to having you where I can touch you. To-night when I go upstairs I'm going to take that damned colorless photograph of you and throw it out the window."

"I must tell you about your photograph," she ventured. "It always stood on the mantel over the stove, and when there was a threatened bombardment I used to put it under—"

"Let's not talk, honey."

When he came out of that particular silence he said abruptly:

"Will Leete is dead."

"Oh, no! Poor Will Leete."

"Died of pneumonia in some God-forsaken hole over there. He's left a wife and nothing much to keep her. That's what comes of mixing in the other fellow's fight. I guess we can get the house as soon as we want it. She has to sell; and it ought to be a bargain."

"Harvey," she said rather timidly, "you speak of the other fellow's fight. They say over there that we are sure to be drawn into it sooner or later."

"Not on our life!" he replied brusquely.

Comments (0)