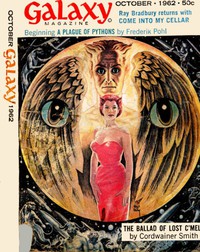

Plague of Pythons, Frederik Pohl [top 100 novels .txt] 📗

- Author: Frederik Pohl

Book online «Plague of Pythons, Frederik Pohl [top 100 novels .txt] 📗». Author Frederik Pohl

The lawyer came back, with the expression of a man who has won a victory he did not expect, and did not want. "Your last chance, Chandler. Change your plea to guilty."

"But—"

"Don't push your luck, boy! The judge has agreed to accept a plea. They'll throw you out of town, of course. But you'll be alive." Chandler hesitated. "Make up your mind! The best I can do otherwise is a mistrial, and that means you'll get convicted by another jury next week."

Chandler said, testing his luck: "You're sure they'll keep their end of the bargain?"

The lawyer shook his head, his expression that of a man who smells something unpleasant. "Your honor! I ask you to discharge the jury. My client wishes to change his plea."

... In the school's chemistry lab, an hour later, Chandler discovered that the lawyer had left out one little detail. Outside there was a sound of motors idling, the police car that would dump him at the town's limits; inside was a thin, hollow hiss. It was the sound of a Bunsen burner, and in its blue flame a crudely shaped iron changed slowly from cherry to orange to glowing straw. It had the shape of a letter "H".

"H" for "hoaxer." The mark they were about to put on his forehead would be with him wherever he went and as long as he lived, which would probably not be long. "H" for "hoaxer," so that a glance would show that he had been convicted of the worst offense of all.

No one spoke to him as the sheriff's man took the iron out of the fire, but three husky policemen held his arms while he screamed.

III

The pain was still burning when Chandler awoke the next day. He wished he had a bandage, but he didn't, and that was that.

He was in a freight car—had hopped it on the run at the yards, daring to sneak back into town long enough for that. He could not hope to hitchhike, with that mark on him. Anyway, hitchhiking was an invitation to trouble.

The railroads were safer—far safer than either cars or air transport, notoriously a lightning-rod attracting possession. Chandler was surprised when the train came crashing to a stop, each freight car smashing against the couplings of the one ahead, the engine jolting forward and stopping again.

Then there was silence. It endured.

Chandler, who had been slowly waking after a night of very little sleep, sat up against the wall of the boxcar and wondered what was wrong.

It seemed remiss to start a day without signing the Cross or hearing a few exorcismal verses. It seemed to be mid-morning, time for work to be beginning at the plant. The lab men would be streaming in, their amulets examined at the door. The chaplains would be wandering about, ready to pray a possessing spirit out. Chandler, who kept an open mind, had considerable doubt of the effectiveness of all the amulets and spells—certainly they had not kept him from a brutal rape—but he felt uneasy without them.... The train still was not moving. In the silence he could hear the distant huffing of the engine.

He went to the door, supporting himself with one hand on the wooden wall, and looked out.

The tracks followed the roll of a river, their bed a few feet higher than an empty three-lane highway, which in turn was a dozen feet above the water. As he looked out the engine brayed twice. The train jolted uncertainly, then stopped again.

Then there was a very long time when nothing happened at all.

From Chandler's car he could not see the engine. He was on the convex of the curve, and the other door of the car was sealed. He did not need to see it to know that something was wrong. There should have been a brakeman running with a flare to ward off other trains; but there was not. There should have been a station, or at least a water tank, to account for the stop in the first place. There was not. Something had gone wrong, and Chandler knew what it was. Not the details, but the central fact that lay behind this and behind almost everything that went wrong these days.

The engineer was possessed. It had to be that.

Yet it was odd, he thought, as odd as his own trouble. He had chosen this car with care. It contained eight refrigerator cars full of pharmaceuticals, and if anything was known about the laws governing possession, as his lawyer had told him, it was that such things were almost never interfered with.

Chandler jumped down to the roadbed, slipped on the crushed rock and almost fell. He had forgotten the wound on his forehead. He clutched the sill of the car door, where an ankh and fleur-de-lis had been chalked to ward off demons, until the sudden rush of blood subsided and the pain began to relent. After a moment he walked gingerly to the end of the car, slipped between the cars, dodged the couplers and climbed the ladder to its roof.

It was a warm, bright, silent day. Nothing moved. From his height he could see the Diesel at the front of the train and the caboose at its rear. No people. The train was halted a quarter-mile from where the tracks swooped across the river on a suspension bridge. Away from the river, the side of the tracks that had been hidden from him before, was an uneven rock cut and, above it, the slope of a mountain.

By looking carefully he could spot the signs of a number of homes within half a mile or so—the corner of a roof, a glassed-in porch built to command a river view, a twenty-foot television antenna poking through the trees. There was also the curve of a higher road along which the homes were strung.

Chandler took thought. He was alive and free, two gifts more gracious than he had had any right to expect. However, he would need food and he would need at least some sort of bandage for his forehead. He had a wool cap, stolen from the high school, which would hide the mark, though what it would do to the burn on his skin was something else again.

Chandler climbed down the ladder. With considerable pain he gentled the cap over the great raw H on his forehead and began to climb the mountain.

He knocked on the first door he came to, a great old three-story house with well tended gardens.

There was a wait. The air smelled warmly of honeysuckle and mown grass, with wild onions chopped down by the blades of the mower. It was pleasant, or would have been in happier times. He knocked again, peremptorily, and the door was opened at once. Evidently someone had been right inside, listening.

A man stared at him. "Stranger, what do you want?" He was short, plump, with an extremely thick and unkempt beard. It did not appear to have been grown for its own sake, for where the facial hair could not be coaxed to grow his skin had the gross pits of old acne.

Chandler said glibly: "Good morning. I'm working my way east. I need something to eat and I'm willing to work for it."

The man withdrew, leaving the upper half of the Dutch door open. As it looked in on only a vestibule it did not tell Chandler much. There was one curious thing—a lath and cardboard sign, shaped like an arc of a rainbow, lettered:

WELCOME TO ORPHALESE

He puzzled over it and dismissed it. The entrance room, apart from the sign, had a knickknack shelf of Japanese carved ivory and an old-fashioned umbrella rack, but that added nothing to his knowledge. He had already guessed that the owners of this home were well off. Also it had been recently painted; so they were not demoralized, as so much of the world had been demoralized, by the coming of the possessors. Even the elaborate sculpturing of its hedges had been maintained.

The man came back and with him was a girl of fifteen or so. She was tall, slim and rather homely, with a large jaw and an oval face. "Guy, he's not much to look at," she said to the pockmarked man. "Meggie, shall I let him in?" he asked. "Guy, you might as well," she shrugged, staring at Chandler with interest but not sympathy.

"Stranger, come along," said the man named Guy, and led him through a short hall into an enormous living room, a room two stories high with a ten-foot fireplace.

Chandler's first thought was that he had stumbled in upon a wake. The room was neatly laid out in rows of folding chairs, more than half of them occupied. He entered from the side, but all the occupants of the chairs were looking toward him. He returned their stares; he had had a good deal of practice lately in looking back at staring faces, he reflected. "Stranger, go on," said the man who had let him in, nudging him, "and meet the people of Orphalese."

Chandler hardly heard him. He had not expected anything like this. It was a meeting, a Daumier caricature of a Thursday Afternoon Literary Circle, old men with faces like moons, young women with faces like hags. They were strained, haggard and fearful, and a surprising number of them showed some sort of physical defect, a bandaged leg, an arm in a sling or merely the marks of pain on the features. "Stranger, go in," repeated the man, and it was only then that Chandler noticed the man was holding a pistol, pointed at his head.

Chandler sat in the rear of the room, watching. There must be thousands of little colonies like this, he reflected; with the breakdown of long-distance communication the world had been atomized. There was a real fear, well justified, of living in large groups, for they too were lightning rods for possession. The world was stumbling along, but it was lame in all its members; a planetary lobotomy had stolen from it its wisdom and plan. If, he reflected dryly, it had ever had any.

But of course things were better in the old days. The world had seemed on the brink of blowing itself up, but at least it was by its own hand. Then came Christmas.

It had happened at Christmas, and the first sign was on nation-wide television. The old President, balding, grave and plump, was making a special address to the nation, urging good will to men and, please, artificial trees because of the fire danger in the event of H-bomb raids; in the middle of a sentence twenty million viewers had seen him stop, look dazedly around and say, in a breathless mumble, what sounded like: "Disht dvornyet ilgt." He had then picked up the Bible on the desk before him and thrown it at the television camera.

The last the televiewers had seen was the fluttering pages of the Book, growing larger as it crashed against the lens, then a flicker and a blinding shot of the studio lights as the cameraman jumped away and the instrument swiveled to stare mindlessly upward. Twenty minutes later the President was dead, as his Secretary of Health and Welfare, hurrying with him back to the White House, calmly took a hand grenade from a Marine guard at the gate and blew the President's party to fragments.

For the President's seizure was only the first and most conspicuous. "Disht dvornyet ilgt." C.I.A. specialists were playing the tapes of the broadcast feverishly, electronically cleaning the mumble and stir from the studio away from the words to try to learn, first, the language and second what the devil it meant; but the President who ordered it was dead before the first reel spun, and his successor was not quite sworn in when it became his time to die. The ceremony was interrupted for an emergency call from the War Room, where a very nearly hysterical four-star general was trying to explain why he had ordered the immediate firing of every live missile in his command against Washington, D. C.

Over five hundred missiles were involved. In most of the sites the order was disobeyed, but in six of them, unfortunately, unquestioning discipline won out, thus ending not only the swearing in, the general's weeping explanation, the spinning of tapes, but also some two million lives in the District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia and (through malfunctioning relays on two missiles) Pennsylvania and Vermont. But it was only the beginning.

These were the first cases of possession seen by the world in some five hundred years, since the great casting out of devils of the Middle Ages. A

Comments (0)