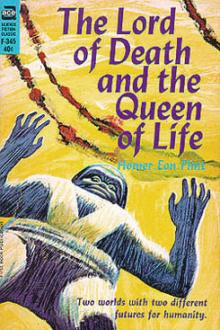

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [some good books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [some good books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

There was nothing on top of the desk save the usual coat of dust. Below, a very wide space had been left for the legs of whoever had used it; and flanking this space were two pedestals, containing what looked to be a multitude of exceedingly small drawers. Smith bent and examined them; apparently they had no locks; and he unhesitatingly reached out, gripped the knob of one and pulled.

Noiselessly, instantaneously, the whole desk crumbled to powder. Startled, Smith stumbled backwards, knocking against the railing. Next instant it lay on the floor, its fragments scarcely distinguishable from what had already covered the surface. Only a tiny cloud of dust arose, and in half a second this had settled.

The three looked at each other significantly. Clearly, the thing that had just happened argued a great lapse of time since the user of that desk officiated in that enclosure. It looked as though Smith's guess of "weeks, perhaps months," would have to be changed to years, perhaps centuries.

"Feel all right?" asked the geologist. Jackson and Smith made affirmative noises; and again they stepped out, this time walking in the aisle along the outer wall. They could see their sky-car plainly through the ovals.

Here the machinery could be examined more closely. They resembled automatic testing scales, said Smith; such as is used in weighing complicated metal products after finishing and assembling. Moreover, they seemed to be connected, the one to the other, with a series of endless belts, which Smith thought indicated automatic production. To all appearances, the dust-covered apparatus stood just as it had been left when operations ceased, an unguessable length of time before.

Smith showed no desire to touch the things now. Seeing this, the geologist deliberately reached out and scraped the dust from the nearest machine; and to the vast relief of all three, no damage was done. The dust fell straight to the floor, exposing a brilliantly polished streak of greenish-white metal.

Van Emmon made another tentative brush or so at other points, with the same result. Clean, untarnished metal lay beneath all that dust. Clearly it was some non-conducting alloy; whatever it was, it had successfully resisted the action of the elements all the while that such presumably wooden articles as the desk and railing had been steadily rotting.

Emboldened, Smith clambered up on the frame of one of the machines. He examined it closely as to its cams, clutches, gearing, and other details significant enough to his mechanical training. He noted their adjustments, scrutinized the conveying apparatus, and came back carrying a cylindrical object which he had removed from an automatic chuck.

"This is what they were making," he remarked, trying to conceal his excitement. The others brushed the dust from the thing, a huge piece of metal which would have been too much for their strength on the earth. Instantly they identified it.

It was a cannon shell.

Again Van Emmon led the way. They took a reassuring glance out the window at the familiar cube, then passed along the aisle toward the farther corner. As they neared it they saw that it contained a small enclosure of heavy metal scrollwork, within which stood a triangular elevator.

The men examined it as closely as possible, noting especially the extremely low stool which stood upon its platform. The same unerodable metal seemed to have been used throughout the whole affair.

After a careful scrutiny of the two levers which appeared to control the thing—"I'm going to try it out," announced Smith, well knowing that the others would have to go with him if they kept the telephones intact. They protested that the thing was not safe; Smith replied that they had seen no stairway, or anything corresponding to one. "If this lift is made of that alloy," admiringly, "then it's safe." But Jackson managed to talk him out of it.

When they returned to the heap of powdered wood which had been the desk, Smith spied a long work-bench under a nearby window. There they found a very ordinary vise, in which was clamped a piece of metal; but for the dust, it might have been placed there ten minutes before. On the bench lay several tools, some familiar to the engineer and some entirely strange. A set of screw-drivers of various sizes caught his eye. He picked them up, and again experienced the sensation of having wood turn to dust at his touch. The blades were whole.

Still searching, the engineer found a square metal chest of drawers, each of which he promptly opened. The contents were laden with dust, but he brushed this off and disclosed a quantity of exceedingly delicate instruments. They were more like dentists' tools than machinists', yet plainly were intended for mechanical use.

One drawer held what appeared to be a roll of drawings. Smith did not want to touch them; with infinite care he blew off the dust with the aid of his oxygen pipe. After a moment or two the surface was clear, but it offered no encouragement; it was the blank side of the paper.

There was no help for it. Smith grasped the roll firmly with his pliers—and next second gazed upon dust.

In the bottom drawer lay something that aroused the curiosity of all three. These were small reels, about two inches in diameter and a quarter of an inch thick, each incased in a tight-fitting box. They resembled measuring tapes to some extent, except that the ribbons were made of marvelously thin material. Van Emmon guessed that there were a hundred yards in a roll. Smith estimated it at three hundred. They seemed to be made of a metal similar to that composing the machines. Smith pocketed them all.

It was the builder who thought to look under the bench, but it was Smith who had brought a light. By its aid they discovered a very small machine, decidedly like a stock ticker, except that it had no glass dome, but possessed at one end a curious metal disk about a foot in diameter. Apparently it had been undergoing repairs; it was impossible to guess its purpose. Smith's pride was instantly aroused; he tucked it under his arm, and was impatient to get back to the cube, where he might more carefully examine his find with the tips of his fingers.

It was when they were about to leave the building that they thought to inspect walls and ceiling. Not that anything worth while was to be seen; the surfaces seemed perfectly plain and bare, except for the inevitable dust. Even the uppermost corners, ten feet above their heads, showed dust to the light of Smith's electric torch.

Van Emmon stopped and stared at the spot as though fascinated. The others were ready to go; they turned and looked at him curiously. For a moment or two he seemed struggling for breath.

"Good Heavens!" he gasped, almost in a whisper. His face was white; the other two leaped toward him, fearful that he was suffocating. But he pushed them away roughly.

"We're fools! Blind, blithering idiots—that's what we are!" He pointed toward the ceiling with a hand that trembled plainly, and went on in a voice which he tried to make fierce despite the awe which shook it.

"Look at that dust again! How'd it get there?" He paused while the others, the thought finally getting to them, felt a queer chill striking at the backs of their necks. "Men—there's only one way for the dust to settle on a wall! It's got to have air to carry it! It couldn't possibly get there without air!

"That dust settled long before life appeared on the Earth, even! It's been there ever since the air disappeared from Mercury!"

IV THE LIBRARY"I thought you'd never get back," complained the doctor crossly, when the three entered. They had been gone just half an hour.

Next moment he was studying their faces, and at once he demanded the most important fact. They told him, and before they had finished he was half-way into another suit. He was all eagerness; but somehow the three were very glad to be inside the cube again, and firmly insisted upon moving to another spot before making further explorations.

Within a minute or two the cube was hovering opposite the upper floor of the building the three had entered; and with only a foot of space separating the window of the sky-car and the dust-covered wall, the men from the earth inspected the interior at considerable length. They flashed a search-light all about the place, and concluded that it was the receiving-room, where the raw iron billets were brought via the elevator, and from there slid to the floor below. At one end, in exactly the same location as the desk Smith had destroyed, stood another, with a low and remarkably broad chair beside it.

So far as could be seen, there were neither doors, window-panes, nor shutters through the structure. "To get all the light and air they could," guessed the doctor. "Perhaps that's why the buildings are all triangular; most wall surface in proportion to floor area, that way."

A few hundred feet higher they began to look for prominent buildings. Only in forgetful moments did either of them scan the landscape for signs of life; they knew now that there could be none.

"We ought to learn something there," the doctor said after a while, pointing out a particularly large, squat, irregularly built affair on the edge of the "business district." The architect, however, was in favor of an exceptionally large, high building in the isolated group previously noted in the "suburbs." But because it was nearer, they maneuvered first in the direction of the doctor's choice.

The sky-car came to rest in a large plaza opposite what appeared to be the structure's main entrance. From their window the explorers saw that the squat effect was due only to the space the edifice covered; for it was an edifice, a full five stories high.

The doctor was impatient to go. Smith was willing enough to stay behind; he was already joyously examining the strange machine he had found. Two minutes later Kinney, Van Emmon, and Jackson were standing before the portals of the great building.

There they halted, and no wonder. The entire face of the building could now be seen to be covered with a mass of carvings; for the most part they were statues in bas relief. All were fantastic in the extreme, but whether purposely so or not, there was no way to tell. Certainly any such work on the part of an earthly artist would have branded him either as insane or as an incomprehensible genius.

Directly above the entrance was a group which might have been labeled, "The Triumph of the Brute." An enormously powerful man, nearly as broad as he was tall, stood exulting over his victim, a less robust figure, prostrate under his feet. Both were clad in armor. The victor's face was distorted into a savage snarl, startlingly hideous by reason of the prodigious size of his head, planted as it was directly upon his shoulders; for he had no neck. His eyes were set so close together that at first glance they seemed to be but one. His nose was flat and African in type, while his mouth, devoid of curves, was simply revolting in its huge, thick-lipped lack of proportion. His chin was square and aggressive; his forehead, strangely enough, extremely high and narrow, rather than low and broad.

His victim lay in an attitude that indicated the most agonizing torture; his head was bent completely back, and around behind his shoulders. On the ground lay two battle-axes, huge affairs almost as heavy as the massively muscled men who had used them.

But the eyes of the explorers kept coming back to the fearsome face of the conqueror. From the brows down, he was simply a huge, brutal giant; above his eyes, he was an intellectual. The combination was absolutely frightful; the beast looked capable of anything, of overcoming any obstacle, mental or physical, internal or external, in order to assert his apparently enormous will. He could control himself or dominate others with equal ease and assurance.

"It can't be that he was drawn from life," said the doctor, with an effort. It wasn't easy to criticize that figure, lifeless though it was. "On a planet like this, with such slight gravitation, there is no need for such huge strength. The typical Mercurian should be tall and flimsy in build, rather than short and compact."

But the geologist differed. "We want to remember that the earth has no standard type. Think what a difference there is between the mosquito and the elephant, the snake and the spider! One would suppose that they had been developed under totally different planetary conditions, instead of all right on the same globe.

"No; I think this monster may have

Comments (0)