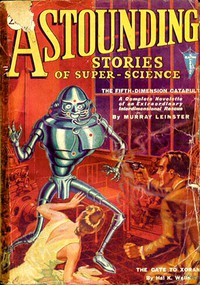

Astounding Stories, April, 1931, Various [diy ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories, April, 1931, Various [diy ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Various

t must have taken us an hour to make it. We should have been caught long before we reached the top, but the giant crabs were slow in their lumbering movements. Despite their evident intelligence, they seemed to lack anything like our railways and automobiles.

The cold gray light of the polar sky came about us; a dull, purple-blue square grew larger above. I clambered over the last rung, flung myself across the top of the metal shaft. Looking down at the tiny fleck of white light so far below, I saw a bit of red move in it.

"A crab!" I shouted. "Hurry!"

Mildred was just below me. I took her pack and helped her over the edge.

Red flame flared up the shaft.

We reached over, seized Ray's arms and fairly jerked him out of the ruby ray.

The bitterly cold wind struck our hot, perspiring bodies as we scrambled down the rungs outside the square metal shaft. Mildred shivered in her thin attire.

"Out of the frying pan into the ice box!" Ray jested grimly as we dropped, to the frozen plain.

Quickly we tore open our packs. Ray and I snatched out clothing and wrapped up the trembling girl. In a few minutes we had her snugly dressed in the fur garments that had been Major Meriden's. Then we got into the quilted garments we had made for ourselves.

The intensely red heat-beam still flared up the shaft. Ray looked at it in satisfaction.

"They'll have it so hot they can't get up it for some time yet," he remarked hopefully.

We shouldered our packs and set out over the wilderness of snow, turning our backs upon the metal-bound lake of fire, with the tall cone of iridescent flame rising in its center.

The deep, purple-blue sky was clear, and, for a rarity, there was not much wind. I doubt that the temperature was twenty below. But it was a violent change from the warm cavern. Mildred was blue and shivering.

n two hours the metal rim below the great white cone had vanished behind the black ice-crags. We passed near the wreck of Major Meriden's plane and reached our last camp, where we had left the tent sledge, primus stove, and most of our instruments. The tent was still stretched, though banked with snow. We got Mildred inside, chafed her hands, and soon had her comfortable.

Then Ray went out and soon returned with a sealed tin of oil from the wrecked plane, with which he lit the primus stove. Soon the tent was warm. We melted snow and cooked thick red soup. After the girl had made a meal of the scalding soup, with the little golden cakes, she professed to be feeling as well as ever.

"We can fix our plane!" Ray said. "There's a perfectly good prop on Meriden's plane!"

We went back to the wreck, found the tools, and removed an undamaged propeller. This we packed on the sledge, with a good supply of fuel for the stove.

"I'm sure we're safe now, so far as the crab-things go," he said. "I don't fancy they'd get around very well in the snow."

In an hour we broke camp, and made ten miles of the distance back to the plane before we stopped. We were anxious about Mildred, but she seemed to stand the journey admirably; she is a marvelous physical specimen. She seemed running over with gay vivacity of spirit; she asked innumerable questions of the world which she had known only at second-hand from her mother's words.

he weather smiled on us during the march back to the plane as much as it had frowned on the terrible journey to the cone. We had an abundance of food and fuel, and we made it in eight easy stages. Once there was a light fall of snow, but the air was unusually warm and calm for the season.

We found the plane safe. It was the work of but a short time to remove the broken propeller and replace it[117] with the one we had brought from the wrecked ship. We warmed and started the engine, broke the skids loose from the ice, turned the plane around, and took off safely from the tiny scrap of smooth ice.

Mildred seemed amazed and immensely delighted at the sensations of her first trip aloft.

A few hours later we were landing beside the Albatross, in the leaden blue sea beyond the ice barrier. Bluff Captain Harper greeted us in amazed delight as we climbed to the deck.

"You're just in time!" he said. "The relief expedition we landed came back a week ago. We had no idea you could still be alive, with only a week's provisions. We were sailing to-morrow. But tell us! What happened? Your passenger—"

"We just stopped to pick up my fiancee," Ray grinned. "Captain, may I present Miss Mildred Meriden? We'll be wanting you to marry us right away."

THE MENACE OF THE INSECTIt is possible that future study may tell man enough about insects to enable him to eradicate them. This, however, is more than can be reasonably expected, for the more we cultivate the earth the better we make conditions for these enemies. The insect thrives on the work of man. And having made conditions ideal for the insect, with great expanses of cultivated food fitted to his needs, it is an optimist who can believe that at the same time we can make other conditions which will be so unfavorable as to cause him to disappear completely. The two things do not go together.

The insect is much better fitted for life than is man. He can survive long periods of famine, he can survive extremes of heat and cold. The insect produces great numbers of young which have no long period of infancy requiring the attention of the parents over a large part of their life. Every function of the insect is directed toward the propagation of the race and the use of minimum effort in every other direction.

It is even possible in some cases, the water flea, for example, for the female to produce young without the necessity of fertilization by the male. In order to perform the necessary work to insure food supplies for the winter other insects have developed highly specialized workers, especially fitted to do particular kinds of labor. Ants and termites are in this class.

If we examine the organization of insects closely we shall find but one point at which they are vulnerable. This is in their lack of ability to reason. True, there is considerable evidence to support the belief that some insects are capable of simple reasoning, but the development in this direction is only of the most elementary nature. As compared to man it is safe to say that they do not reason. They are guided by instinct.

This again is the most efficient way to organize their affairs. It requires no long period of training. They can begin performing all their useful functions as soon as their bodily development makes it possible. No one need teach them how to catch their prey, how to build their nests or shelters. Instinct takes care of this. But this, obviously the best system in a world wholly governed by instinct, is not so desirable when the instinctively actuated insect encounters another form of life, as man, which is capable of reason. The reasoning individual can play all kinds of tricks on the individual who is actuated by instinct.

[118]

My whole attention was focused upon the strange beings.

The Ghost World

By Sewell Peaslee Wright

My whole attention was focused upon the strange beings.

The Ghost World

By Sewell Peaslee Wright

was asleep when our danger was discovered, but I knew the instant the attention signal sounded that the situation was serious. Kincaide, my second officer, had a cool head, and he would not have called me except in a tremendous emergency.

"Hanson speaking!" I snapped into the microphone. "What's up, Mr. Kincaide?"

"A field of meteorites sweeping into our path, sir." Kincaide's voice was tense. "I have altered our course as much as I dared and am reducing speed at emergency rate, but this is the largest swarm of meteorites I have ever seen. I am afraid that we must pass through at least a section of it."

"With you in a moment, Mr. Kincaide!" I dropped the microphone and snatched up my robe, knotting its cord about me as I hurried out of my stateroom. In those days, interplanetary ships did not have their auras of repulsion rays to protect[119] them from meteorites, it must be remembered. Two skins of metal were all that lay between the Ertak and all the dangers of space.

I took the companionway to the navigating room two steps at a time and fairly burst into the room.

Kincaide was crouched over the two charts that pictured the space around us, microphone pressed to his lips. Through the plate glass partition I could see the men in the operating room tensed over their wheels and levers and dials. Kincaide glanced up as I entered, and motioned with his free hand towards the charts.

One glance convinced me that he had not overestimated our danger. The space to right and left, and above and below, was fairly peppered with tiny pricks of greenish light that moved slowly across the milky faces of the charts.

From the position of the ship, represented as a glowing red spark, and measuring the distances roughly by means of the fine black lines graved in both directions upon the surface of the chart, it was evident to any understanding observer that disaster of a most terrible kind was imminent.

incaide muttered into his microphone, and out of the tail of my eye I could see his orders obeyed on the instant by the men in the operating room. I could feel the peculiar, sickening surge that told of speed being reduced, and the course being altered, but the cold, brutally accurate charts before me assured me that no action we dared take would save us from the meteorites.

"We're in for it, Mr. Kincaide. Continue to reduce speed as much as possible, and keep bearing away, as at present. I believe we can avoid the thickest portion of the field, but we shall have to take our chances with the fringe."

"Yes, sir!" said Kincaide, without lifting his eyes from the chart. His voice was calm and businesslike, now; with the responsibility on my shoulders, as commander, he was the efficient, level-headed thinking machine that had endeared him to me as both fellow-officer and friend.

Leaving the charts to Kincaide, I sounded the general emergency signal, calling every man and officer of the Ertak's crew to his post, and began giving orders through the microphone.

"Mr. Correy,"—Correy was my first officer—"please report at once to the navigating room. Mr. Hendricks, make the rounds of all duty posts, please, and give special attention to the disintegrator ray operators. The ray generators are to be started at once, full speed." Hendricks, I might say, was a junior officer, and a very good one, although quick-tempered and excitable—failings of youth. He had only recently shipped with us to replace Anderson Croy, who—but that has already been recorded.[2]

[2] "The Dark Side of Antri," in the January, 1931, issue of Astounding Stories.

These preparations made, I glanced at the twin charts again. The peppering of tiny green lights, each of which represented a meteoritic body, had definitely shifted in relation to the position of the strongly-glowing red spark that was the Ertak, but a quick comparison of the two charts showed that we would be certain to pass through—again I use land terms to make my meaning clear—the upper right fringe of the field.

The great cluster of meteorites was moving in the same direction as ourselves now; Kincaide's change of course had settled that matter nicely. Naturally, this was the logical course, since should we come in contact with any of them, the impact would bear a relation to only the difference in our speeds, instead of the sum, as would be the case if we struck at a wide angle.

t was difficult to stand without grasping a support of some kind, and walking was almost impossible, for

Comments (0)