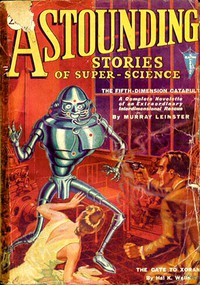

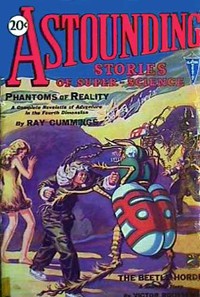

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931, Various [latest novels to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931, Various [latest novels to read .txt] 📗». Author Various

The stalagmites in the cavern tower 100 feet high. The age of the cavern was put at 60,000,000 years by Dr. Willis T. Lee of the National Geographic Society, after his survey three years ago.

The caverns were discovered fifteen years ago by a New Mexican cowboy named Jim White, according to Mr. Nicholson. White was riding across a desert waste one day when he saw what appeared to be smoke from a volcano. After riding three hours in the direction of the smoke he discovered that it was an enormous cloud of bats issuing from the mouth of a gigantic cavern. He decided the cavern deserved exploration, and a few years later he and a Mexican boy were lowered in a barrel over the 750-foot cliff which overhangs the cavern.

The stalagmites of the cavern, according to Mr. Nicholson, are very vibrant and resonant. One can play a “xylophone solo” on them with practice, he said, but it is dangerous, since a certain pitch would crack them.

The temperature of the cavern is 56 degrees Fahrenheit, never varies, day and night, winter and summer. The air is purified every twenty-four hours in some mysterious fashion, though there are no air currents. This is explained by the theory that there exists a great subterranean stream at a lower level, probably 1,200 feet down.

Specimens of stalagmites will be collected and reconstructed for the American Museum of Natural History. The explorers expect to find also flying fish, flying salamanders, rare insects and thousands of bats. A Government representative will go along, and drawings and motion pictures will be made.

A Meeting Place for Readers of

Astounding Stories A Letter and Comment

Three or four times in the year we have been issuing Astounding Stories the Editor has received letters calling attention to fancied scientific errors in our stories. All these letters were published, but until now we have not cut in on the space of “The Readers’ Corner” to answer such objections because they were very obviously the result of hasty or inaccurate readings.

The other week one more such letter reached us—from Mr. Philip Waite, this time—claiming that there was “an atrocious flaw” in two stories of Captain S. P. Meek’s. This we could not let go unanswered, first because of the strong terms used, and second because the objection would sound to many like a true criticism; so we turned the letter over to Captain Meek, and his answer follows Mr. Waite’s letter below.

We welcome criticism of stories in our “The Readers’ Corner.” Never yet have we withheld from it any criticism or brickbats of importance—and we never intend to. But space is limited; there’s not room now for all the good letters that come in; and we do not want to intrude too much with editorial comment. Therefore when we do not stop and answer all criticisms we are not necessarily admitting they are valid. In most cases everyone will quickly see their lack of logic or accuracy, and in the rest we will ask you to remember that our Staff is meticulously careful about the scientific facts and laws and possibilities that enter our stories, so it’s extremely unlikely that anything very “atrocious” will get by.

Well, we’d better cut short now, before we take up too much “Corner” room. But first, thanks to Captain Meek for going to the trouble of defending two stories that needed no defense. And thanks, too, to Mr. Waite, for his kindness in writing in to inform us of what he thought—unquestionably because of hasty reading—were errors.—The Editor.

P. S. (Now we’ll have to be super careful of our science, for if Mr. Waite ever gets anything on us—!!)

Dear Editor:

Just a note to tell you to keep up the good work. There was an atrocious flaw, however, in the two stories by Capt. S. P. Meek about the Heaviside Layer. How, may I ask, do meteors penetrate through that imaginary substance which is too much for a powerful space flyer? Also, how about refraction? A substance denser than air would produce refraction that would have been noticed long ago. I don’t mind minor errors, but an author has no right to ignore the facts so outrageously. Fiction goes too far when an author can invent such false conditions.

In the latest issue “Stolen Brains” was fine, up to the Dr. Bird standard. “The Invisible Death” was good enough, but too much like the general run to be noteworthy. “Prisoners on the Electron”—couldn’t stomach it. Too hackneyed. “Jetta of the Lowlands,” by Ray Cummings; nuff said. “An Extra Man”—original idea and perfectly written. One of the reasons I hang on to Science Fiction. A perfect gem.—Philip Waite, 3400 Wayne Ave., New York, N. Y.

Dear Editor:

May I use enough space in your discussion columns to reply briefly to the objections raised to the science in my two stories, “Beyond the Heaviside Layer” and “The Attack from Space”? Understand that I am not arguing that there actually is a thick wall of semi-plastic material surrounding the earth through which a space flyer could not pass. If I did, I would automatically bar myself from writing interplanetary stories, a thing that is far from my desires. I do wish to point out, however, that such a layer might exist, so far as we at present know. The objections to which I wish to reply are two: first, “How do meteors pass through that imaginary substance which is too much for a powerful space flyer?” and second, “How about refraction?”

To reply to the first we must consider two things, kinetic energy and resistance to the passage of a body. The kinetic energy of a moving body is represented by the formula ½mv2 where m is the mass of the body and v the velocity. The resistance of a substance to penetration of a body is expressed by the formula A fc where A is the area of the body in contact with the resisting medium and fc is the coefficient of sliding friction between the penetrating body and the resisting medium. Consider first the space flyer. To hold personnel the flyer must be hollow. In other words, m must be small as compared to A. A meteor, on the other hand, is solid and dense with a relatively large m and small A. Given a meteor and a space flyer of the same weight, the volume of the meteor would be much smaller, and as the area in contact with the resisting medium is a function of volume, the total resistance to be overcome by the space flyer would be much greater than that to be overcome by the meteor. Again, consider the relative velocities of a meteor and a space flyer coming from the earth toward the heaviside layer. The meteor from space would have an enormous velocity, so great that if it got into even very rare air, it would become incandescent. As it must go through dense air, the space flyer could attain only a relatively low velocity before it reached the layer. Remember that the velocity is squared. A one thousand pound meteor flying with a velocity 100 times that of the space ship would have 1002 or 10,000 times the kinetic energy of the space ship while it would also have less friction to overcome due to its smaller size.

If my critic wishes to test this out for himself, I can suggest a very simple experiment. Take a plank of sound pine wood, two inches thick by twelve inches wide and four feet long. Support it on both ends and then pile lead slabs onto it, covering the whole area of the board. If the wood be sound the board will support a thousand pounds readily. Now remove the lead slabs and fire a 200 grain lead bullet at the board with a muzzle or initial velocity of 1,600 feet per second. The bullet will penetrate the board very readily. Consider the heaviside layer as the board, the space ship as the lead slabs and the bullet as the meteor and you have the answer.

Consider one more thing. According to the stories, the layer grew thicker and harder to penetrate as the flyer reached the outer surface. The meteor would strike the most viscous part of the layer with its maximum energy. As its velocity dropped and its kinetic energy grew less, it would meet material easier to penetrate. On the other hand the flyer, coming from the earth, would meet material easy to penetrate and gradually lose its velocity and consequently its kinetic energy. When it reached the very viscous portion of the layer, it would have almost no energy left with which to force its way through. Remember, the Mercurians made no attempt to penetrate the layer until a portion of it had been destroyed by Carpenter’s genius.

As for the matter of refraction. If you will place a glass cube or other form in the air, you will have no difficulty in measuring the refraction of the light passing through it. If, however, the observer would place himself inside a hollow sphere of glass so perfectly transparent as to be invisible, would not the refraction he would observe be taken by him to be the refraction of air when in reality it would be the combined refraction of the glass sphere and the air around him?

I have taken glass as the medium to illustrate this because my critic made the statement that “a substance denser than air would produce refraction that would have been noticed long ago.” However nowhere in either story is the statement made that the material of the heaviside layer was denser than air. The statement was that it was more viscous. Viscosity is not necessarily a function of density. A heavy oil such as you use in the winter to lubricate your automobile has a much higher viscosity than water, yet it will float on water, i. e. it is less dense. There is nothing in the story that would prevent the heaviside layer from having a coefficient of refraction identical with that of air.

To close, let me repeat that I am not arguing that such a layer exists. I do not believe that it does and I do believe that my generation will probably see the first interplanetary expedition start and possibly see the first interplanetary trip succeed. I do, however, contend that the science in my stories is accurate until it transcends the boundaries of present day knowledge and ceases to be science and becomes “super-science,” and that my super-science is developed in a logical manner from science and that nothing in present knowledge makes the existence of such a layer impossible—S. P. Meek. Capt. Ord. Dept., U. S. A.

Likes Long NovelettesDear Editor:

I have just finished reading the August issue of your magazine. I am going to rate the different stories in per cents. 100% means excellent; 75% fairly good; 50% passable; 25% just an ordinary story.

I give “Marooned Under The Sea,” by Paul Ernst, 100%; 75% for “The Attack From Space,” by Captain S. P. Meek. “The Problem in Communication,” by Miles J. Breuer, M. D. and “Jetta of the Lowlands,” by Ray Cummings; 50% for “The Murder Machine,” by Hugh B. Cave and “Earth, The Marauder,” by Arthur J. Burks; 25% for “The Terrible Tentacles of L-472,” by Sewell Peaslee Wright.

I am happy to say that since I have been reading your magazine, I have induced at least ten of my friends to be constant readers of this magazine.

I like the long novelettes much better than continued novels, and hope that in the future we will get bigger and better novelettes.—Leonard Estrin, 1145 Morrison Ave., Bronx, N. Y.

Hasn’t DecidedDear Editor:

Move over, you old-timers, and let a newcomer say something.

A few months ago I didn’t read any Science Fiction. Now I read it all. I haven’t decided yet which magazine I like best.

I was a little disappointed when you didn’t have another story in the September copy by R. P. Starzl, who wrote “Planet of Dread.” I thought you would hold on to a good author when you find one.

I would also like another story by the fellow who wrote the serial “Murder Madness.”

I like short stories best.

That idea of a mechanical nirvana in Miles J. Breuer’s story was good.

“Jetta of the Lowlands?” Opinion reserved. I like the action of the story, but I hate a hero who is always bragging about himself.

Don’t think I’m complaining, but nothing is perfect.

Why not try to get a story of A. Merritt’s, or Ralph Milne Farley’s?—A. Dougherty, 327 North Prairie Ave., Sioux Falls, So. Dak.

AnnouncementDear Editor:

May I enter “The Readers’ Corner” to announce that a branch of The Scienceers has recently been formed in Clearwater, Florida, by a group of Science Fiction enthusiasts?

We have a library of 175 Science Fiction magazines, including a complete file of Astounding Stories to date. We hold weekly meetings at which scientific topics are discussed, and current Science Fiction stories commented upon.

As the first branch of The Scienceers, we are striving to achieve a success that will be a mark for other branches to aim at.—Carlton Abernathy, P. O. Box 584, Clearwater, Fla.

From Merrie EnglandDear Editor:

I came across your May publication of Astounding Stories the other day, and

Comments (0)