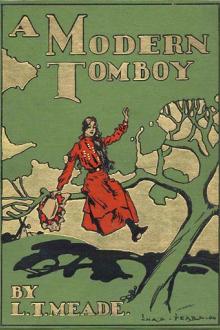

A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls, L. T. Meade [ready to read books .txt] 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

Book online «A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls, L. T. Meade [ready to read books .txt] 📗». Author L. T. Meade

"Oh, dear, how am I to endure that?"

"You will endure it when I give you a piece of news. It is arranged that little Agnes comes also, and"——

"Oh, have you settled that, you darling?"

"Partly. And Miss Frost comes, too, as they want another governess; and your dear mother, who needs change, will spend the time with one of her sisters in Scotland. Now you know exactly what is before you, and I must be off. I trust you, Irene. You won't disappoint me? If I thought you could, I don't really know what would become of me."

CHAPTER XXI. A REAL ROUSING FRIGHT.Wonderful to relate, the holidays passed smoothly enough. Hughie was the sort of boy to be touched by Rosamund's words. No one had before appealed to him just in Rosamund's way. He found, too, considerable pleasure and interest on his own account at The Follies, for Lady Jane was singularly kind to him, and gave him a pony to ride, and he was permitted the rare indulgence of going with the gamekeeper into the woods to take his first lesson in partridge-shooting; but this came later on.

Meanwhile Miss Frost made a great effort to recover her self-control; but such an agony of jealousy had taken possession of the poor lady that she could scarcely bear to be in the society either of her pupil or her little sister. Irene exercised more and more influence over Agnes, and for a long time that influence was altogether for good. When the child asked simple questions Irene replied simply. She felt ashamed of her own want of knowledge on many particulars. She went regularly to church twice every Sunday because little Agnes thought that no living person could do otherwise. She did not at all want to go, and she trembled as much as ever when the choir sang, and when the place became hushed and people called themselves "miserable sinners," and looked so unconcerned and so well-dressed. But for the sake of Agnes she restrained herself, for Agnes' little, pale, calm face appeared not to think at all about the matter.

Nevertheless, it was scarcely possible that such a cloudless state of things could continue. As to Hughie, he and Irene were more or less neutral, neither speaking much to the other. They were both absolutely different, but both were absolutely without fear.

There came a day, however, when Irene took it into her wild little head that Hughie needed a lesson to be taught him.

"I know by his looks," she thought, "that he hates my loving Agnes so much."

Accordingly, she made up her mind to administer a lesson, and to make it as stiff a piece of terrorism as she could devise.

"He thinks he knows a great deal; but I'll teach him!" thought the girl.

Some of her old wicked spirit had come back to her. She had no longer any lessons to employ her time; she had no longer Rosamund's wholesome influence—Rosamund who was in Switzerland, and whose letters, delightful as they were, could not take the place of her constant presence.

The day was a sultry one toward the end of August. Miss Frost, pale and dejected, was seated in one of the arbors. She was doing some needlework, and little Agnes was sitting on a low stool at her sister's feet. Miss Frost looked up when Irene suddenly entered.

"I wonder," she said, "if you and Agnes would go to town for me after lunch? Mother says you may have the pony-trap and drive in. I want you to get"——

She produced a list of all sorts of materials, including a new doll for Agnes.

"I want Agnes to have a doll, and a cradle to put it in at night, and she shall make the clothes for it. Between you and me, we can show her how. Would you like it, Agnes darling?"

"Oh, shouldn't I just love it!" said little Agnes. "Fancy my being your baby, and then having a baby of my own! Oh, it seems altogether too beautiful! Isn't she sweet, Emily?"

Miss Frost looked with her nervous eyes at her pupil. Irene's own bright eyes looked back in reply. They were full of dancing mischief.

"Mothery will give you some money to buy the necessary things," she said. "I have spoken to her about it; indeed, she is going with you, and lunch is to be a quarter of an hour earlier."

"But would you—would you," said Miss Frost, who was trembling all over with delight at the thought of having her beloved little sister all to herself for a whole afternoon—"wouldn't you like to keep Agnes? I would buy the things for her."

She felt herself very noble as she made this remark.

"No," said Irene, shaking her head. "No; I want Agnes to choose her own doll. You can have a boy-dolly or a girl-dolly," she said, "just as you please. There is a beautiful shop at Dartford, in the High Street, where you can buy everything you want. It is called Millar's. You know all about it, don't you, Frosty? Now, there is the luncheon-bell."

The luncheon-bell sounded. Miss Frost, little Agnes, Irene, and the rest of the party all assembled in the cool dining-room.

Soon after lunch, Lady Jane, Agnes, and Miss Frost started for Dartford, and Irene turned and faced Hughie.

"Hughie," she said, "would you like to come for a row on the lake with me?"

"If you wish," he replied.

He had kept his promise to Rosamund so far. He had made no further inquiries with regard to Irene. He had tried, as he expressed it, to wash his hands of her. He did not like her. He felt that he never could like her. There was something to him repugnant about her. He had a kind of uncanny feeling that she was a sort of changeling; that she could do extraordinary, defiant, and marvelous things. Now, as she looked full up at him, trying to steady her face, and trying to look as like an ordinary girl as possible, he endeavored to conceal a queer sort of fear which stole suddenly over his heart. He remembered the old stories; the servants who shrank from her, the wild creatures that seemed to be her constant companions, and the tricks she was capable of playing on any one.

"I will go with you, of course," he said. "Do you want me to row?"

"No; I want you to sit in the stern and steer. Will you come? Just wait a minute. I'll be ready in no time."

She flew upstairs, and came down in the obnoxious red dress, which she had not worn for such a long time. It made a queer change in her, giving her a more elf-like appearance than usual.

"Why do you wear that? It isn't pretty," said Hughie.

"Never you mind whether it is pretty or not," retorted Irene.

"Well, I'll try not; but a fellow must make remarks. You know, you look ripping in your white dresses, and that silk thing you wear in the evening; but I don't like that."

"Don't you? Well, I do. Anyhow, I'm going to wear it to-day while we are having our fun on the lake. It's just a perfect day for the lake. Do you know, there's a storm coming on."

As Irene spoke she fixed her bright eyes on the sky. It was blue over the house; but in the distance, coming rapidly nearer and nearer, was a terrible black cloud—a cloud almost as black as ink—and already there were murmurs in the trees and cawings among the birds, the breeze growing stronger and stronger—the prelude to a great agitation of nature.

"I suppose we won't go on the lake to get drowned," said Hughie. "That is a thunder-cloud."

"Never mind; it will be all the greater fun. I am in my red dress, and you can put on any shabby clothes you happen to have. If you are going to be a counter-jumper you must have got some very shabby things."

"Why do you speak to me in that tone?" said Hughie.

"Oh, I don't know. I didn't mean anything. You can put on anything you like, and you needn't come if you don't want to; but I thought you were a plucky sort of chap."

"You may be quite sure I am. Of course I will come with you. Let us run down to the boat-house. Perhaps," continued Hughie, struggling with the promise he had made to Rosamund, "the storm may go off in another direction, and we sha'n't have it."

"I see you are awfully afraid of it, and it mayn't come here at all," said Irene, who knew perfectly well that it would, for the cloud was coming more and more in the direction of the house each moment.

In a very short time the two children were in the boat, Irene taking both the oars, and giving Hughie simple directions to steer straight for the stream in the middle of the lake.

"Now I will give him a real rousing fright," she said to herself. "After that perhaps he will be my slave, the same as Carter was. Anyhow, I have a crow to pluck with him; and the storm, and my knowledge of the water, and his absolute ignorance will enable me to win the day."

Aloud, she said in a gentle voice, "Perhaps you'd like to take the oars?"

"I will if you like," said Hughie; "but the fact is, I'm not very good at rowing. I have never been much in a boat."

"Ah! I thought as much. But I can teach you. Come and sit here."

They had just entered the stream, which made the lake dangerous even on a calm day. Hughie stumbled to his feet; Irene sat in the stern, took the ropes, and skillfully guided the boat into the centre of the stream. It began to rock tremendously.

"Now pull! Pull hard!" she said to the boy.

Just then a blinding flash of lightning came across their faces.

"Oh!" said Hughie, "the storm is on us. It will rain in a few minutes. Hadn't we better get back?"

"What a coward you are!" said Irene. "It is the most awful fun to be out on the lake in a storm like this. Ah! do you hear that growl?"

"But I can't manage the boat a bit."

"I thought all boys could manage boats. You don't expect a girl to do it—a girl out in the midst of a storm of this sort? Besides, I must put up my umbrella or I shall be soaked."

"But I told you it would rain. You shouldn't have come out," said Hughie, who felt more annoyed, distressed, and angry than he had ever felt in his life before. He felt that suddenly the boat was quite unmanageable, that it was rocking and racing and taking them he did not know where.

All of a sudden Irene sprang to her feet.

"Get back into the stern," she said. "Sit quite still, and let me take the oars. I wanted to see if you could row. I see you can't. There is another flash of lightning. Don't be frightened. I know you are; but try to keep it under. I have something to say to you."

She seated herself, and the two children faced each other. The flash of lightning was followed by a crashing peal of thunder. The trees bowed low to meet the gale; the frightened birds, the swans and others, took shelter where they could best find it; but as yet there was not a drop of rain.

"How hot it is!" said Irene. "Let us fly down the stream."

"What do you mean by that?" said Hughie, whose freckled face was deadly white.

"I will tell you if you like; but don't speak."

He looked at her with fascinated eyes. In her red dress, with her witch-like face and glancing, dancing, naughty eyes, she became to him for the moment an object of absolute terror. Was this the gentle and exceedingly pretty girl whom little Agnes so adored? He was alone with her, and they were, so to speak, flying through the water, although she scarcely touched the oars, allowing them to lie almost idle by her side.

Suddenly she shipped them and bent toward him.

"We needn't row any more," she said. "We are in the current. The current will take us. Hughie, can you swim?"

"I don't know anything about swimming," he said.

"Well, that is rather bad for you; for in about five minutes of this sort of thing

Comments (0)